Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

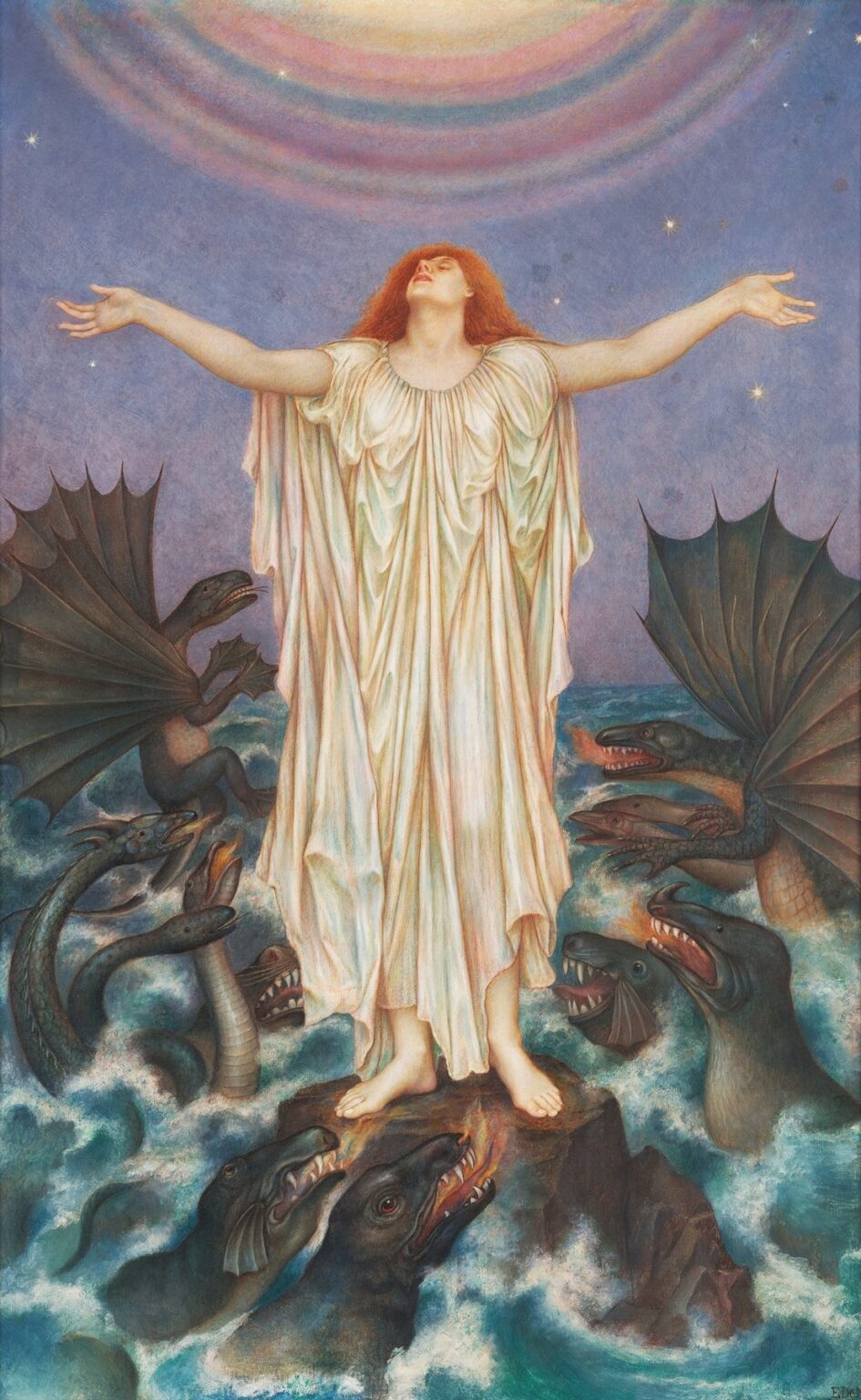

Evelyn De Morgan’s S.O.S. (1916) confronts viewers with a stirring allegory of human desperation and divine intervention amid the tumult of war. Painted during the height of World War I, the canvas depicts a solitary female figure standing atop a rocky outcrop as monstrous sea creatures surge around her. She lifts her arms skyward toward a spectral rainbow of light emanating from the heavens—a celestial call for aid and an emblem of hope. De Morgan, a committed pacifist and spiritualist, channels her opposition to conflict into this poignant image of distress and deliverance. Through her masterful synthesis of classical form, Symbolist imagery, and moral urgency, S.O.S. invites reflection on the ravages of violence, the power of faith, and the possibility of redemption in desperate times.

Historical Context

By 1916, Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) had established herself as a leading voice among British women artists. Trained in the Pre‑Raphaelite tradition, she evolved toward a mature Symbolism infused with Christian and Theosophical ideals. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 deeply affected her pacifist convictions; she refused to profit from war commissions and instead turned her art toward protest and prayer. S.O.S. emerges from this milieu of global conflict, when the horrors of industrialized warfare spurred artists to seek spiritual solace and moral clarity. De Morgan’s canvas responds directly to the contemporary cry of millions suffering on land and sea, framing individual distress as part of a collective human plea for deliverance.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

S.O.S. is organized around a strong vertical axis that runs from the basin of churning sea at the bottom, through the outstretched arms of the central figure, up to the rainbow‑tinted light at the top. The rocky ledge upon which the woman stands acts as a narrow fulcrum between chaos and calm: below, the sea creatures writhe in violent motion; above, the heavenly shaft remains serene and immaterial. De Morgan balances this vertical thrust with the horizontal sweep of the rainbow’s arc, which echoes the curve of the sea’s cresting waves. The diagonal lines of the woman’s body—her tilted head, extended arms, and bent knees—create a dynamic dialogue between earth and sky, grounding her desperate appeal while guiding the viewer’s gaze upward toward hope. The limited depth of field, confined to foreground sea and midground rock, concentrates emotional intensity and prevents distraction.

Use of Color and Light

Color in S.O.S. functions as both emotional intensifier and symbolic guide. The sea is rendered in deep blues and greens, layered with translucent glazes that convey depth and menace. White foam sparkles against the dark water, highlighting the violence of the waves. The sea creatures—stylized hybrids of serpents, dragons, and sea monsters—are painted in muted grays and umbers, their jagged teeth and spiny fins accentuated by touches of crimson. In stark contrast, the central figure is illuminated by a pale, almost ghostly light that renders her skin in soft ivory tones. Her white drapery, clinging to her form, captures reflections of the rainbow—subtle washes of rose, mauve, and gold that echo the heavenly promise. The rainbow itself is painted with exceptional translucency, each band of color seamlessly merging into the next, as though spun from celestial mist. This chromatic juxtaposition between the oppressive gloom below and the ethereal radiance above underscores the painting’s thematic tension between despair and deliverance.

Symbolism and Thematic Depth

At its core, S.O.S. is an allegory of moral and spiritual rescue. The title’s reference to the universal maritime distress signal reinforces the painting’s portrayal of existential peril. The monstrous sea creatures embody not only physical danger but also the collective horrors of war—chaos, violence, and dehumanization. The central figure, however, stands resolute, her vulnerability paradoxically strengthened by her courage to appeal beyond her immediate circumstances. By raising her arms to the rainbow light, she enacts both surrender and supplication, acknowledging human frailty while invoking divine compassion. The rainbow, a biblical sign of covenant and hope, signals the possibility of renewal even amid devastation. In this interplay of mythic sea monsters, human supplicant, and heavenly arc, De Morgan transforms individual suffering into a universal plea for mercy and a testament to the enduring power of faith.

The Central Figure: Courage and Vulnerability

De Morgan’s portrayal of the lone woman is suffused with emotional nuance. Her body, rendered with Pre‑Raphaelite precision, displays both anatomical accuracy and graceful form. Her stance is one of poised tension: knees bent to maintain balance, fingers splayed as though feeling the energy of the light, neck arched backward in an open, vulnerable gesture. Her face, tilted upward, reveals a blend of anguish, determination, and longing. By exposing her vulnerability—her near‑nudity and isolation—De Morgan highlights the bravery required to confront overwhelming forces. The white drapery, though scant, serves as a visual halo that both humanizes and sanctifies her. In placing a woman at the center of this allegory, De Morgan asserts feminine agency and moral strength, aligning with her broader advocacy for women’s social and spiritual authority.

The Sea Creatures and Visual Metaphor

The surrounding monsters combine classical mythic vocabulary with modern dread. Their sinuous bodies twist through the waves, mouths agape in silent snarl, ready to drag the supplicant beneath the surface. De Morgan’s careful rendering of fins, scales, and spines underscores the creative tension between beauty and terror—an aesthetic hallmark of the Pre‑Raphaelite‑Symbolist synthesis. The creatures’ varied anatomies suggest the multifaceted nature of threat: some resemble serpents of ancient legend, others evoke industrial machinery’s impersonal menace. In this way, the sea itself becomes a metaphor for the maelstrom of wartime society, where individuals risk being engulfed by forces beyond their control. Yet the figure’s immovable posture and the absence of direct confrontation—she does not brandish a weapon—signal that the true battle lies in moral and spiritual realms rather than physical combat.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

S.O.S. exerts a powerful emotional pull through its stark contrasts and focused narrative moment. Viewers are drawn to the figure’s desperate plea, compelled to share in her fear and hope. The visceral depiction of the sea’s violence elicits empathy and unease, while the celestial light offers solace and anticipation. De Morgan’s skillful integration of these elements ensures that the painting functions as an immersive experience: one senses both the physical chill of the ocean spray and the warmth of the rainbow’s glow. By refusing to shy away from the painting’s moral clarity—evil versus hope—De Morgan invites viewers to confront their own responses to suffering and to consider the role of compassion and faith in times of crisis.

Artistic Technique and Brushwork

A closer look at S.O.S. reveals De Morgan’s adept fusion of tight detailing and atmospheric effect. The sea creatures’ scales and spines are rendered with fine, crisp strokes, lending them a tangible presence amid the swirling water. In contrast, the rainbow and the figure’s drapery are built up through multiple layers of glaze—thin washes of pigment that create luminosity and depth. The foam of the waves combines stippled highlights with sweeping scumbles that capture water’s unpredictable movement. Subtle impasto accents on the figure’s shoulders and the monsters’ teeth create catchlights that enhance realism. De Morgan’s mastery of both linear precision and painterly diffusion underscores her ability to evoke palpable physicality alongside transcendent symbolism.

Pacifism and Personal Conviction

While S.O.S. can be appreciated as a universal allegory, it is deeply rooted in De Morgan’s personal pacifism and wartime activism. Refusing to accept war commissions, she instead offered paintings like this as moral testimonies, urging viewers to recognize the human cost of conflict. The title’s maritime distress signal serves as a coded plea from the artist herself—a call for urgent intervention to save lives and restore peace. In choosing a solitary female figure rather than a male soldier or nationalistic iconography, De Morgan challenges prevailing wartime narratives and emphasizes the universal vulnerability of the civilian population, particularly women and children. This gendered perspective aligns with her broader feminist critique of militarism and her belief in compassion as the ultimate path to reconciliation.

Legacy and Significance

In the decades following World War I, Evelyn De Morgan’s reputation waned, as modernist movements embraced abstraction and disavowed overt moralizing. Yet recent reevaluations of women’s contributions to late‑Victorian and Edwardian art have restored her prominence. S.O.S. stands as one of her most direct and affecting war‑time allegories, its dramatic iconography resonating with contemporary audiences facing global crises. The painting’s fusion of mythic imagery, feminist agency, and pacifist conviction anticipates later 20th‑century art that grapples with trauma and moral responsibility. Exhibitions of De Morgan’s oeuvre now place S.O.S. alongside other peace‑inspired works, underscoring its enduring relevance as both historical document and universal moral appeal.

Conclusion

Evelyn De Morgan’s S.O.S. (1916) remains a powerful testament to art’s capacity to confront human suffering and to channel hope. Through her masterful composition, vivid contrasts of color and light, and layered symbolism, she creates a visceral allegory of despair and deliverance. The lone figure—vulnerable yet courageous—stands as an emblem of moral agency against the monstrous forces of violence and chaos. The rainbow‑tinted light from above offers not only visual drama but a profound symbol of promise that transcends temporal conflict. In capturing this moment of plea and potential salvation, De Morgan affirms the enduring power of faith, compassion, and art itself to illuminate the darkest hours.