Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

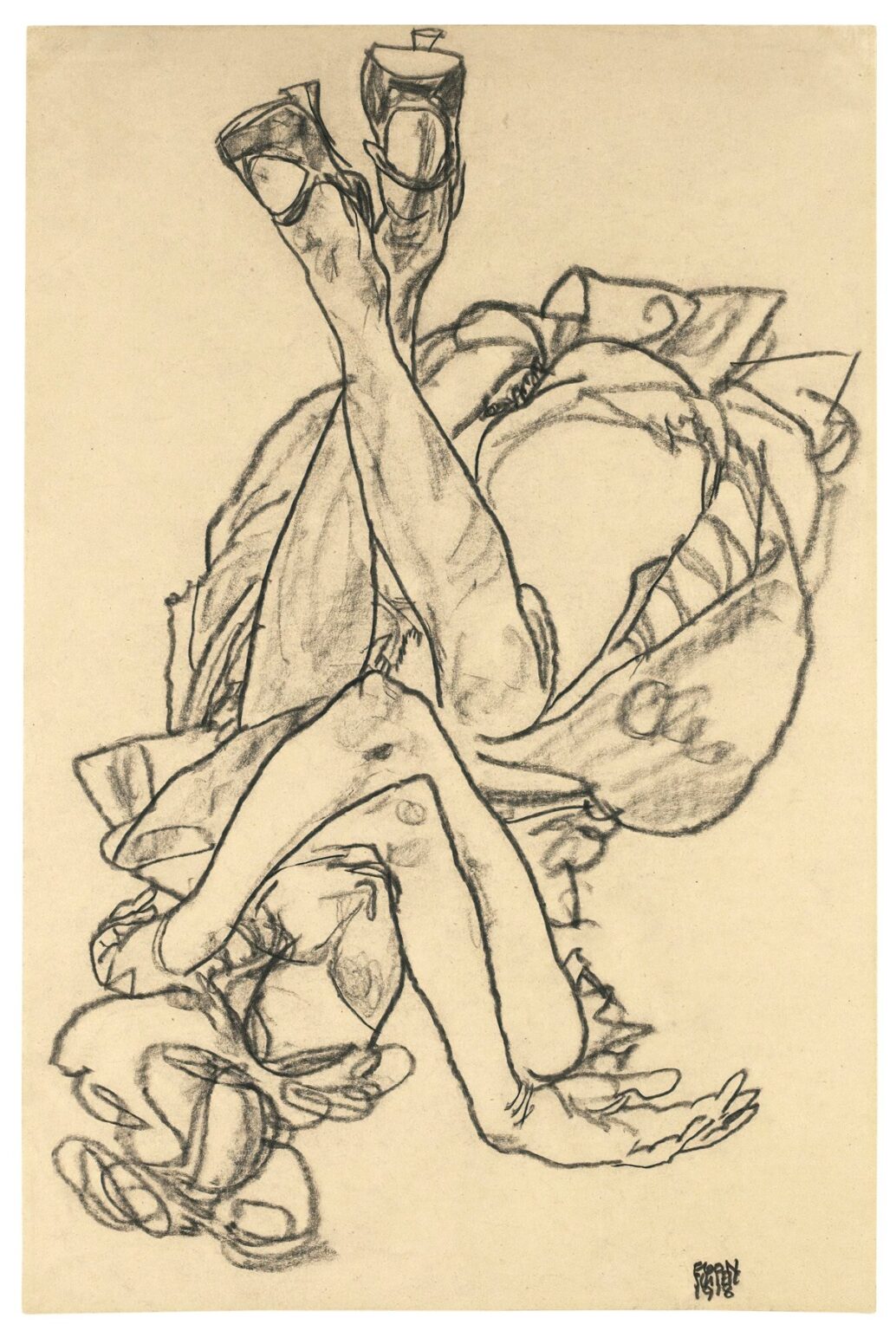

Egon Schiele’s Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs (1918) encapsulates the artist’s late-career mastery of line, form, and raw psychological intensity. Executed on the eve of his untimely death, the drawing presents a young woman rendered in swirling, urgent charcoal strokes, her body contorted into a striking X-shape. Unlike traditional reclining nudes that evoke languor and softness, Schiele’s subject conveys tension and vulnerability, her limbs intersecting in a dynamic interplay of angles that defies classical repose. This analysis considers the drawing’s historical moment, compositional innovation, formal techniques, emotional resonance, and enduring place within Schiele’s oeuvre, revealing how a simple charcoal sketch becomes a profound exploration of human fragility and expressive power.

Historical Context

The year 1918 marked both the apex and the final chapter of Schiele’s career. Europe was mired in the chaos of World War I, and Austria-Hungary was fracturing. Schiele himself faced personal upheaval: he had been conscripted for military service, briefly imprisoned for alleged immorality, and was grappling with the Spanish flu that would claim his life mere months after creating this work. In this climate of crisis and uncertainty, artists turned inward, seeking to articulate the psychological shocks of their age. Expressionism, with its emphasis on subjective experience and distortion, provided a powerful outlet. Schiele, following in the footsteps of Gustav Klimt and his German contemporaries, embraced a fiercely personal aesthetic. His late drawings, including this reclining figure, bear the imprint of wartime anxieties, mortality, and a heightened awareness of the body’s impermanence.

Medium and Technique

Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs is rendered in charcoal on buff-colored paper, a choice that underscores Schiele’s interest in immediacy and graphic intensity. The charcoal lines vary in weight—from bold, confident outlines to delicate, almost whisper-like hatchings—creating a vivid sense of volume and texture. In some areas, Schiele pushes the charcoal to produce deep, velvety blacks; in others, he employs rapid, sketchy gestures that barely touch the paper. These varied strokes capture both the solidity of bone and the trembling of flesh. The absence of erasure or correction marks speaks to the artist’s decisiveness and willingness to embrace trace marks as part of the drawing’s energy. The blank background serves not as empty space but as a stark foil that amplifies the figure’s presence and the charged quality of the line work.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Schiele subverts traditional reclining-composition norms by presenting the figure in a striking diagonal across the page. The crossed arms and legs form an X-shape that fractures the pictorial plane into interlocking triangles, creating dynamic tension. The subject’s head tilts toward the upper left corner, while her feet extend toward the upper right, giving the impression of movement even in stillness. There is no sense of floor or support; the woman seems suspended, as if floating in an indeterminate space. This compositional ambiguity heightens the drawing’s psychological impact. Rather than inviting a voyeuristic gaze into a comfortable interior, Schiele confronts viewers with an almost disquieting immediacy, forcing an engagement with the figure’s raw, exposed limbs and the stark interplay of shadow and line.

Line as Expressive Force

Line is the lifeblood of Schiele’s practice, and this drawing exemplifies its expressive potential. Schiele’s contours are never merely descriptive; they pulsate with emotional charge. The lines outlining the arms and legs are drawn with muscular force, their thickness varying to emphasize tension at joints and musculature. Around the torso and hips, the lines soften into feathered hatching, suggesting the pliancy of skin. The hands, with their elongated fingers, are delineated with meticulous attention, their gesture evoking both invitation and restraint. Schiele often allows lines to overlap, creating visual vibrations that mirror psychological unrest. This dynamic line work dismantles any illusion of a static, contained form, instead revealing the body as a site of continual motion and shifting emotional states.

Anatomy and Distortion

Schiele’s relationship to anatomy is unconventional: he knows the body’s structure yet willingly distorts it to serve expressive ends. In this drawing, the limbs are elongated beyond natural proportions, the knees hinge at sharp angles, and the hands appear almost disembodied. These distortions do not signal error but intention—they underscore the figure’s emotional state, a tension between control and surrender. The exaggeration of the legs, for example, draws attention to the raw vulnerability of the nude form, while the dramatic angle of the arms creates a protective barrier around the torso. Schiele’s distortions thus become a visual language of feeling: the body speaks not merely through gesture but through the very shape and direction of its parts.

Light, Shadow, and Negative Space

Although rendered solely in charcoal, the drawing conveys a rich interplay of light and shadow. Schiele uses denser charcoal build-up to model the figure’s curves and create areas of deep shadow beneath the legs and around the shoulders. In contrast, large expanses of the paper remain untouched, serving as negative space that highlights the figure’s outlines. These blank areas function as luminous highlights, suggesting where light would graze the limbs. The strategic absence of mark-making thus becomes as vital as the charcoal itself, allowing the paper’s tone to assert the figure’s volume. This use of negative space also contributes to the overall tension: the subject seems both defined and yet partially absorbed by the emptiness around her.

Psychological Resonance

More than a study of nude form, Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs penetrates the sitter’s interior life. The figure’s face is tilted away, partially obscured by tangled hair, denying viewers a full view of her expression. This refusal of direct gaze intensifies the drawing’s emotional charge: she becomes both a subject under observation and a self-contained psyche resisting easy access. The crossed limbs can be read as a protective gesture, a way of guarding inner vulnerability, while the overall contortion suggests unease. In the context of 1918, this tension may echo collective anxieties about life, death, and the disorienting aftermath of war. The drawing thus operates on both personal and universal registers, capturing the timeless complexity of human emotion.

Schiele’s Late Style

Created just months before his death, this drawing belongs to Schiele’s late style, characterized by an economy of means and a distilled intensity. Unlike his earlier works, which often featured elaborate settings or multiple figures, these late drawings strip away extraneous elements, focusing on singular forms bathed in psychological depth. The heightened directness of charcoal sketches from this period reveals an artist at the peak of formal confidence, willing to lay bare his rawest emotional insights without artifice. In Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs, Schiele channels his acute sensitivity to bodily form and vulnerability into a single, powerful statement. The drawing stands alongside other late masterworks as testament to his ability to fuse technical virtuosity with existential urgency.

Technical Innovations

Schiele’s approach in this drawing reflects several technical innovations. His use of charcoal as both drawing and painting medium blurs disciplinary boundaries, allowing for painterly shading alongside graphic precision. The visible underlayers of lighter strokes beneath heavier marks demonstrate an iterative process, with each pass adding depth rather than obscuring what came before. Schiele also experiments with line density, using clusters of rapid hatching to build shadow and shifting to single, determined strokes to define edge. This dynamic alternation animates the drawing’s surface, creating a sense of living texture. By exposing the creative process—sketchy lines, overdrawn contours, partially erased areas—Schiele foregrounds the work’s materiality and affirms the act of making as integral to its meaning.

Relation to Schiele’s Oeuvre

While Schiele produced numerous reclining nudes throughout his career, this 1918 drawing stands apart for its visceral immediacy and formal austerity. In earlier works, he often contextualized figures within interiors or landscapes, employing color and decorative motifs. Here, he reduces the composition to essentials: line, form, and bare paper. This focus on the figure as an autonomous entity reflects his deepest formal convictions. Comparisons with Klimt’s decorative nudes reveal Schiele’s conscious departure from ornamentation toward raw expression. Moreover, the drawing’s stark vulnerability aligns it with his self-portraits from the same period, in which he confronted his own mortality. In this sense, the reclining woman and the artist himself share a kinship: both subject and creator become sites of exploration into the fragility and strength of the human condition.

Influence and Reception

Although Schiele’s late drawings were less widely exhibited during his lifetime, their posthumous impact has been profound. Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs has influenced generations of artists who value the expressive potential of graphic media. Its bold distortions and psychological intensity resonated with later Expressionists and informed post-war figurative trends in Europe and America. Scholars have lauded the drawing for its formal economy and emotional clarity, often citing it as a key example of Schiele’s mastery of line. Today, it is recognized not merely as a work of historical interest but as a timeless articulation of human vulnerability, bridging the personal and the universal in ways that continue to inspire.

Preservation and Exhibition History

Charcoal drawings are notoriously fragile, yet Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs has survived in remarkable condition thanks to careful conservation. Historically, Schiele’s works on paper were less likely to be acquired by major museums until decades after his death, but this drawing eventually entered prominent collections where it has been exhibited in retrospectives that chart Expressionism’s evolution. Its inclusion in thematic shows on war-time art or the Spanish flu pandemic underscores its resonance with historical trauma. Conservation efforts have focused on stabilizing the paper, preventing charcoal flaking, and ensuring controlled light exposure to preserve the drawing’s subtle tonal variations. As a result, modern audiences can still experience the immediacy of Schiele’s gestures and the haunting vitality of his late vision.

Continuing Relevance

In an age marked by renewed interest in mental health, trauma, and the body’s vulnerabilities, Schiele’s drawing speaks across a century. Its exploration of tension, protection, and exposure mirrors today’s conversations about boundaries and personal resilience. Contemporary artists in disciplines as diverse as performance, photography, and digital media cite Schiele’s graphic directness and willingness to portray raw emotion as formative. The drawing’s nearly abstract composition—crossed limbs disrupting the page—anticipates modern concerns with fragmentation and reassembly of the self. In academic settings, it serves as a case study in line psychology, the ethics of representation, and the power of minimal means to convey maximal depth.

Conclusion

Egon Schiele’s Girl Lying on Her Back with Crossed Arms and Legs stands as a culminating testament to an artist who pushed the boundaries of figure drawing into the realm of existential inquiry. Through dynamic composition, masterful charcoal technique, and unflinching psychological insight, Schiele transforms a reclining nude into a powerful exploration of human fragility, protection, and exposure. Created amid war, personal upheaval, and the imminence of death, the drawing bears witness to the artist’s profound engagement with his own mortality and the universal condition. Today, it remains a vital work, its bold lines and haunting presence continuing to captivate, challenge, and inspire.