Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

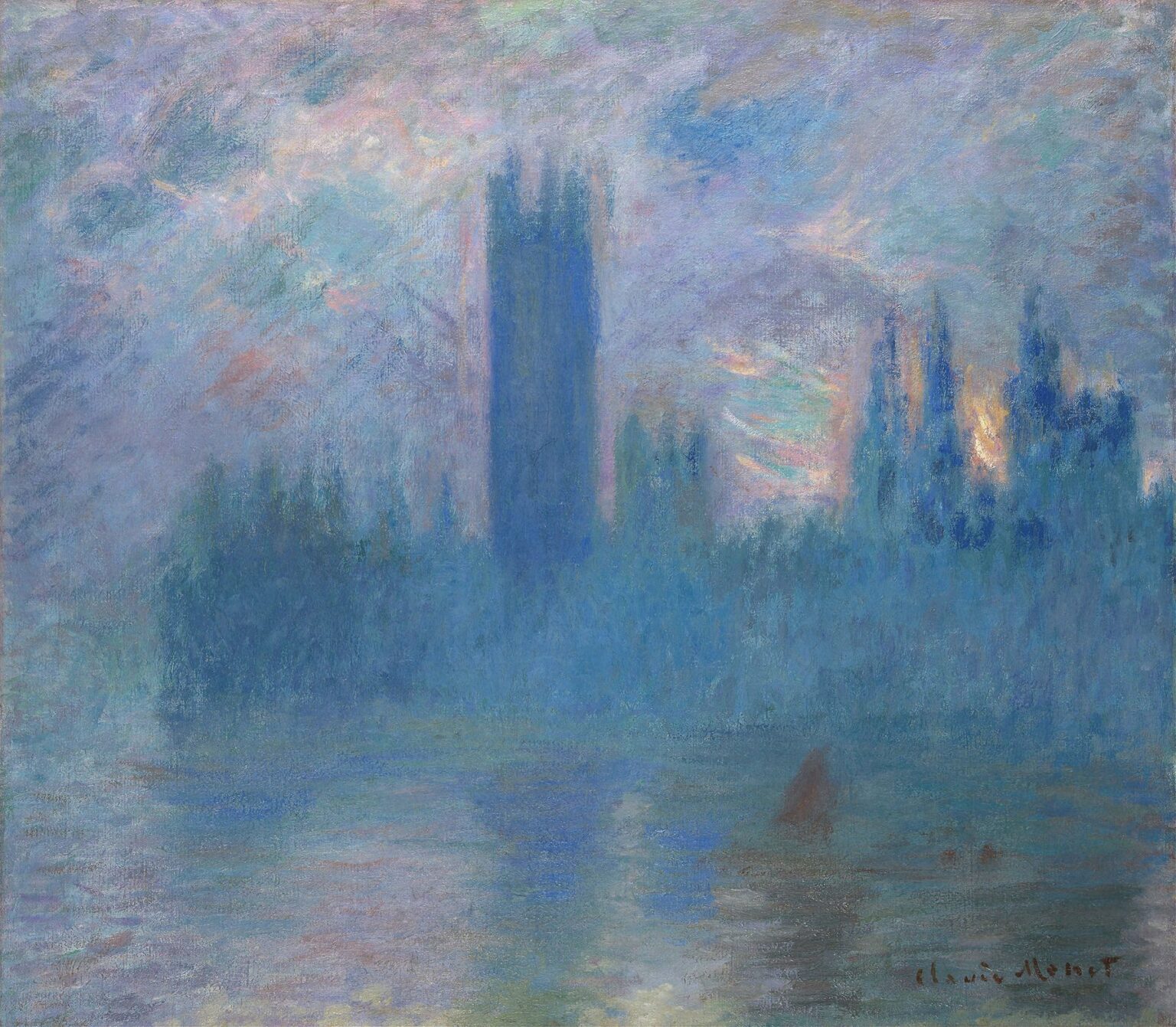

Claude Monet’s Houses of Parliament, London (1900) stands as a landmark in his renowned London series, capturing the iconic Gothic silhouette of Britain’s seat of power shrouded in atmospheric haze. Far from a strictly architectural study, Monet’s canvas is a sensory immersion in the interplay of fog, sunlight, and the rippling Thames. Through his signature loose brushwork, daring color juxtapositions, and radical plein-air technique, Monet transforms the familiar skyline into a transcendent vision of light and form. This analysis explores how the painting exemplifies Monet’s mature Impressionist approach, his fascination with urban atmospheres, and its enduring impact on modern art.

Historical Context

By the dawn of the 20th century, Europe was in the throes of rapid industrialization and urban expansion. London, the heart of a global empire, epitomized the era’s contradictions: majestic architectural heritage amid the murk of factory smoke and river fog. Monet first visited London in 1870–71, painting river views during the Franco-Prussian War. He returned in 1899–1901, drawn by the city’s pervasive fog—a combination of natural mist and coal smoke known as “pea soup” fog. This environment offered Monet an unprecedented opportunity: to depict the dissolution of form in shifting light and haze. Houses of Parliament arises from this period of artistic reinvention, reflecting the Impressionist commitment to capturing transient optical effects in a modern urban landscape.

Monet’s London Series

Monet’s London paintings constitute one of his most sustained series, rivaling his studies of Rouen Cathedral and Waterloo Bridge. Over several winters, he painted the Thames embankment, the bridges, and the Houses of Parliament under varying weather and times of day. His method involved setting up portable easels on scaffolding or barges, braving cold winds and swirling smoke to record immediate impressions. Each canvas became a snapshot of a fleeting moment: the sun glinting through yellow-green fog, the silhouette of Big Ben softened by mist, the Thames shimmering with muted reflections. Together, these works exemplify Monet’s pursuit of light as subject, dissolving solid forms into fields of color and atmosphere.

Composition and Perspective

In Houses of Parliament, London, Monet positions the Houses’ vast façade across the middle of the canvas, its towers rising in softened verticals against a sky of swirling haze. The perspective is slightly oblique, suggesting Monet’s vantage on the south bank of the Thames, perhaps near Westminster Bridge. The river occupies nearly half the painting, its surface articulated by horizontal brushstrokes that mirror the sky’s color palette. A solitary small sailboat drifts near the right foreground, its dark hull anchoring the composition and providing human scale. By balancing the horizontal expanse of water with the vertical thrust of the Gothic towers, Monet achieves a rhythmic harmony that guides the viewer’s eye across the canvas.

Treatment of Light and Atmosphere

Light in this painting is both subject and medium. Monet dissolves the Houses of Parliament in a luminous veil of fog, using a high-key palette of pale rose, lavender, and buttery yellow. Through thin, overlapping layers, he conveys the sun’s diffuse glow as it filters through polluted air. Highlights on the river’s ripples pick up the same hues, creating a continuous environment where water and sky share chromatic DNA. Shadows, rather than being dark and opaque, become cooler notes—soft blues and violets—that suggest depth without compromising the overall luminosity. This celebration of atmospheric effects over crisp detail marks Monet’s radical redefinition of landscape and cityscape painting.

Color Palette and Optical Mixing

Monet’s daring use of complementary colors intensifies the painting’s vibrancy. He places warm, sunlit tones—cadmium yellow and rose madder—against cooler blues and greens, allowing the viewer’s eye to blend them optically. This technique produces shimmering edges and dynamic surfaces that seem to move as one shifts perspective. In the sky, strokes of pale yellow mingle with lavender-gray, while the river’s surface features streaks of emerald green alongside flecks of peach and pink. The silhouette of the building emerges through muted blues, barely delineated against the luminous fog. By refraining from pre-mixing and instead applying pure pigments side by side, Monet achieves a living canvas that responds to ambient light in the gallery.

Brushwork and Surface Rhythm

Monet’s brushwork in Houses of Parliament, London is a study in controlled spontaneity. Short, vertical dashes suggest the towers’ spires, while broader horizontal sweeps articulate the river’s expanse. In the sky, swirling circles and diagonal strokes evoke drifting clouds and smoke eddies. The cumulative effect is a tapestry of gestures: each mark retains its individuality yet contributes to the painting’s overall unity. This rhythmic application of paint mirrors the natural oscillations of fog banks and water currents, inviting viewers to sense the motion underlying the still image. The textured surface also captures light variably, enhancing the painting’s immersive quality.

Spatial Depth and Dissolution of Form

Despite its pervasive atmosphere, the painting retains a convincingly three-dimensional quality. Monet achieves depth through graduated color saturation and clarity. Foreground reflections on the Thames are painted with relatively clear brushstrokes and slightly higher contrast, suggesting proximity. In contrast, the far bank and the building’s façade are softly focused, their edges blurred by fog. Vertical towers recede into the haze, becoming mere tonal suggestions. This graduated retreat in detail and warmth reflects the Impressionist principle of atmospheric perspective: distance is defined by color temperature and sharpness rather than linear vanishing points alone.

Human Presence and Scale

While the painting emphasizes architectural majesty and natural phenomenon, Monet includes subtle human markers. A small sailboat in the foreground offers a point of entry—a reminder of daily life on the Thames. Its solitary presence underscores the monumental scale of the Parliament complex and the vastness of the environment. The absence of crowds or detailed figures shifts focus to the interplay of light and form, yet the boat’s inclusion preserves a humanistic dimension. Through this delicate balance, Monet highlights both the city’s civic grandeur and the individual’s place within an ever-changing urban ecosystem.

Symbolism and Modernity

Houses of Parliament, London can be read as a symbolic meditation on modernity’s dual forces: technological progress and environmental change. The Industrial Revolution endowed cities with new architectural feats—railways, bridges, gothic revival monuments—but also with pervasive smoke and pollution. Monet’s foggy haze blurs the line between natural mist and industrial smog, raising questions about progress’s costs. Yet his treatment is never didactic; instead, he finds beauty in the ephemeral interplay of light and pollution. The painting thus becomes a nuanced portrait of an age defined by both innovation and atmospheric transformation.

Monet’s Late Impressionist Vision

By 1900, Monet’s approach had evolved beyond early Impressionism’s bright spontaneity to deeper explorations of atmosphere and abstraction. In Houses of Parliament, the painting’s subject almost dissolves, foreshadowing Monet’s later Water Lilies series in Giverny, where recognizable forms give way to near-total abstraction in color fields. His London canvases represent a crucial transitional phase: the cityscape serving as a pretext for pure explorations of light’s mutability. This late Impressionist vision situates Monet as a forerunner of modernist abstraction, using visible brushwork and chromatic vibration to evoke sensation before form.

Technical Analysis and Conservation

Contemporary conservation studies of Houses of Parliament, London have employed infrared reflectography and pigment analysis to uncover Monet’s working methods. Underlayers of warm ochre ground provide luminosity beneath cooler overlays. Pigments identified include ultramarine, cobalt violet, and chrome yellow, applied in both thin glazes and thicker impasto. Infrared imaging reveals preliminary charcoal sketches mapping the towers’ placement before Monet’s signature freehand application. Conservation efforts have focused on stabilizing minor craquelure in heavy impasto areas and removing aged varnish that dulled the original color contrasts, restoring the painting’s intended vibrancy.

Exhibition History and Reception

First exhibited in Paris at Galerie Durand‐Ruel in 1900, Houses of Parliament, London attracted both acclaim and puzzlement. Critics celebrated Monet’s evocation of atmosphere but lamented the lack of sharp detail. Over subsequent decades, as Impressionism gained wider acceptance, the painting became a highlight of retrospective exhibitions, often cited as a critical bridge between representational art and abstraction. It passed through prominent private collections before entering a leading museum, where it remains a touchstone for studies of late Impressionism and urban landscape painting.

Influence and Legacy

Monet’s London series, with Houses of Parliament as a cornerstone, influenced a generation of artists grappling with urban subjects. The British artist Walter Sickert and American painter John Singer Sargent both explored cityscapes imbued with atmospheric effects, drawing inspiration from Monet’s methods. In the 20th century, Abstract Expressionists such as Mark Rothko and Cy Twombly—fascinated by color fields and gestural brushwork—acknowledged Monet’s impact on their approach to abstraction. Today, Houses of Parliament, London continues to inspire photographers, filmmakers, and contemporary painters seeking to capture the interplay of architecture, light, and atmosphere in dynamic urban settings.

Cultural Significance

Beyond its art‐historical importance, Monet’s depiction of the Houses of Parliament holds cultural resonance. It portrays a symbol of democracy and governance diffused in mist, inviting reflection on the impermanence of power and the ephemeral nature of human institutions. The painting’s atmospheric ambiguity mirrors London’s historical narrative—a city perpetually renewing itself amid fog, smoke, and rain. For modern viewers, it serves as both a document of a bygone industrial era and a timeless meditation on the fragile beauty lodged between earth, water, and sky.

Conclusion

Houses of Parliament, London (1900) stands as a crowning achievement of Claude Monet’s mature Impressionism. Through his daring use of color, liberated brushwork, and profound sensitivity to atmospheric nuance, Monet transforms London’s iconic Gothic silhouette into a lyrical vision of light and haze. The painting bridges the world of tangible architecture and the realm of pure sensation, foreshadowing modernist abstraction while celebrating the sensual immediacy of the urban landscape. Over a century after its creation, Monet’s masterpiece continues to captivate, reminding us that beauty often resides in the interplay of form and mist, solidity and light.