Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

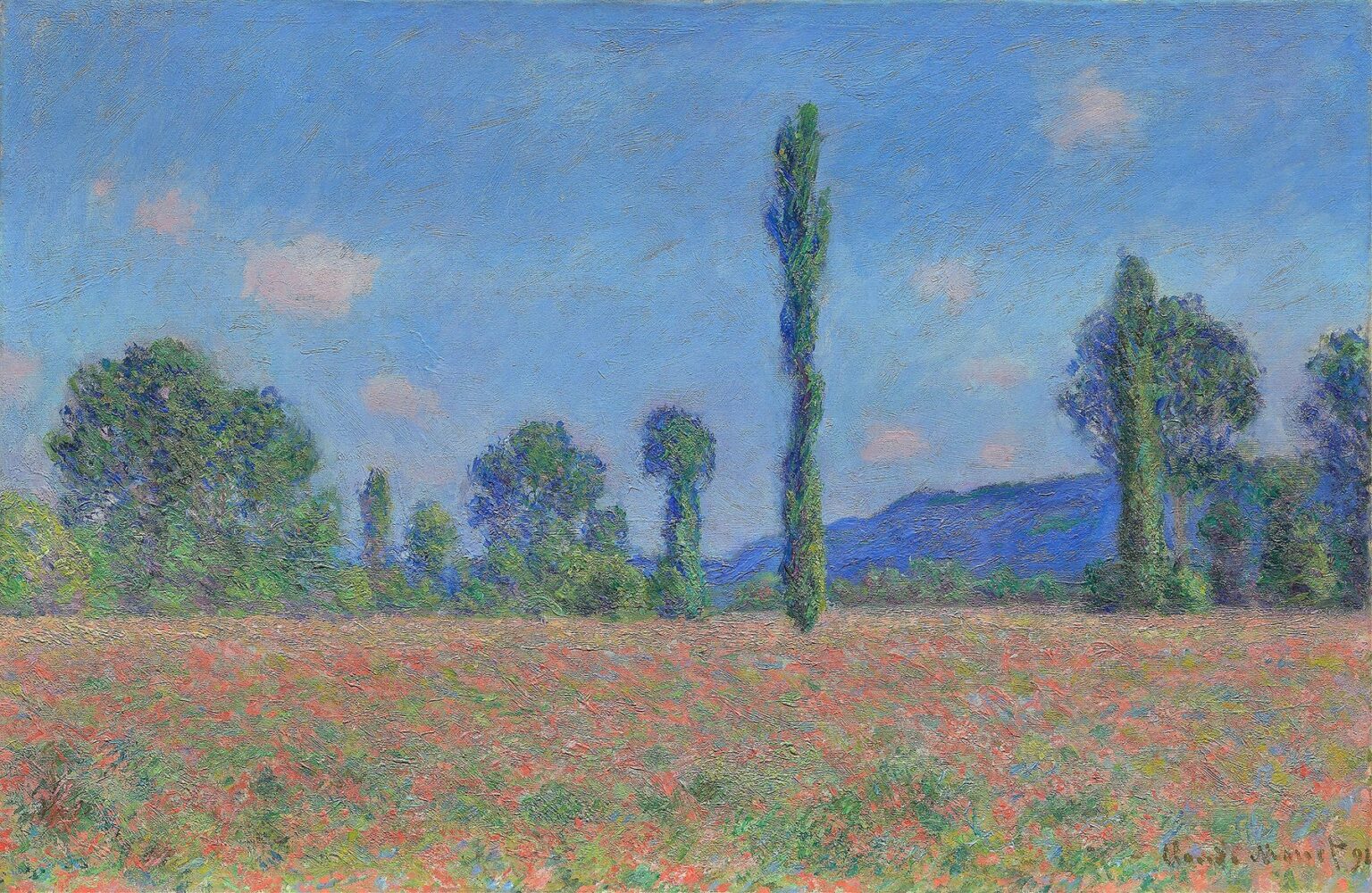

Claude Monet’s Poppy Field (Giverny) (1890) stands as one of the most exuberant manifestations of his mature Impressionist technique. Far from a mere depiction of flora, this canvas embodies Monet’s lifelong quest to translate the ephemeral qualities of light, color, and atmosphere into paint. In this work, he merges the cultivated gardens of his beloved Giverny estate with the wild profusion of poppies carpeting the surrounding fields. Through dynamic brushwork, a daring palette of complementary hues, and an uncompromising commitment to plein-air observation, Monet offers viewers an immersive experience of summer’s vitality in Normandy. This analysis explores how Poppy Field epitomizes the artist’s evolving vision and the broader currents of Impressionism at the close of the 19th century.

Historical Context: Monet and the Impressionist Movement

By 1890, Monet had already played a leading role in the formation of Impressionism, participating in its first exhibition in 1874 and subsequent shows in 1876, 1877, and 1880. These early exhibitions, marked by critical skepticism but public curiosity, established Monet’s reputation as an innovator committed to direct perception and loose, vibrant brushstrokes. Throughout the 1880s, he experimented with increasingly ambitious subjects: water lilies, cathedral façades, and coastal cliffs. When he took up permanent residence in Giverny in 1883, Monet found an ideal locus for sustained inquiry into light’s mutability. Poppy Field emerges from this fertile period, reflecting both the artist’s technical mastery and his deepening philosophical engagement with nature as subject and collaborator.

Giverny: Garden, Estate, and Artistic Laboratory

Monet’s move to Giverny in 1883 marked a profound turning point. He transformed a modest farmhouse into a living canvas, designing gardens with Japanese bridges, water lilies, bamboo plantings, and borders of colorful blooms. Surrounding the water garden lay expansive meadows where wild poppies flourished in early summer. Monet painted these fields alongside his more celebrated water-lily pond, viewing both as complementary arenas for exploring color and light. His dedication to cultivating—and painting—Giverny as an artistic laboratory demonstrates his holistic vision: art and landscape were inseparable, each feeding back into the other in an ongoing dialogue between painter and environment.

Plein-Air Practice: Capturing the Moment

Central to Poppy Field is Monet’s plein-air methodology. Working outdoors, he confronted rapidly shifting weather, changing sun angles, and gusts of wind buffeting his canvas. To preserve spontaneous impressions, Monet employed a portable easel and painted in successive sessions, often revisiting the same spot at slightly different times of day. Unlike studio-completed works based on sketches, Poppy Field bears the directness of these outdoor experiences. The brushstrokes retain the energy of Monet’s hand, the surface texture echoing the sensation of wind in the grasses and the warm glow of midday sunlight. This immediacy of execution remains a hallmark of Impressionism’s radical break from academic traditions.

Composition: Structure within Spontaneity

At first glance, Poppy Field seems governed purely by color and light, but a closer reading reveals a carefully balanced structure. Monet divides the canvas into three horizontal bands: a foreground dominated by vibrant poppy blooms, a middle ground where a low line of trees anchors the horizon, and a sky punctuated by soft, drifting clouds. The horizon sits just above the vertical midpoint, allowing the lower field to occupy more visual weight while granting the sky ample space to convey atmospheric depth. The trees—rendered in cool greens and purples—provide a restful break from the fiery reds below, guiding the viewer’s eye laterally across the scene. Within this grid, Monet introduces subtle diagonals in the undulating field, creating a sense of movement and leading the eye toward distant vistas beyond Giverny’s borders.

Brushwork and Surface Rhythm

Monet’s brushwork in Poppy Field exemplifies the textural diversity that breathes life into the canvas. In the foreground, he lays down quick, hooked strokes of cadmium red, vermilion, and rose madder to denote clusters of poppies. Between these dabs, shorter green flicks imply the grassy undergrowth. The midground trees, in contrast, are built up through small, vertical strokes that suggest leaf clusters catching the sun and casting dapples of shadow. Above, the sky’s broad, horizontal sweeps of cerulean and titanium white offer a calmer counterpoint to the energetic field below. These varied marks, each retaining its individuality, coalesce into a cohesive whole when viewed at arm’s length, engaging the viewer’s eye in active optical mixing.

Color Harmony and Optical Mixing

Monet’s palette in Poppy Field reflects a masterful synthesis of complementary colors. He deliberately places warm reds next to cool greens, creating vibrant contrasts that intensify luminosity through optical mixing. Touches of orange and pink in the blooms find their counterparts in subtle violet shadows cast by undergrowth. The horizon trees, composed of ultramarine and emerald strokes, resonate against the white-pink sky, where slight tints of rose echo the field’s hues. By avoiding heavy pre-mixing, Monet allows pigments to interact dynamically on the canvas, resulting in a chromatic vibrancy that changes with viewing distance and light conditions. This technique captures not only local color—the perceived hue of an object—but the ambient light that suffuses the landscape.

Light and Atmospheric Effects

Light functions as the unifying agent in Poppy Field. Monet captures a midday glow that suffuses both earth and sky in a near-uniform brightness, softened by thin cloud cover. The sparkle of reflected light on the petals is suggested through small, concentrated dabs of pure white and pale yellow. Shadows, rarely rendered as stark forms, appear as cooler mixtures of violet and blue, lending depth without harsh contrast. The sky’s pale pink and lavender wisps speak to moisture-laden air typical of early summer in Normandy. Through these flourishes, Monet conveys not just the appearance of the scene but its sensory ambiance—the warmth on skin, the rustle of grasses in wind, the faint headiness of summer blooms.

Spatial Depth and Perspective

Despite its broad swath of foreground color, Poppy Field achieves convincing spatial depth through several Impressionist strategies. First, the scale and clarity of detail decrease with distance: distant blooms merge into red fields whose textures are hinted at rather than delineated. The horizon line’s trees are less sharply defined, their forms suggested through softer strokes and cooler tones. Atmospheric perspective further enhances recession, as the sky near the horizon takes on warmer, paler hues that contrast with the cooler, pure blue overhead. Monet thereby mimics human vision, where near objects appear rich in texture and color, and distant ones appear lighter, cooler, and less distinct.

Emotional Resonance and Poetic Undercurrents

While rooted in observation, Poppy Field transcends mere representation to evoke an emotional tenor. The vast field of blossoms conveys a sense of abundance and summer’s fleeting joy. Yet the horizon’s distant trees and the sky’s shifting clouds introduce a subtle melancholy—a reminder of time’s passage and nature’s constant renewal. The viewer senses a quiet undercurrent of reflection: the field is at once a symbol of vitality and a memento mori of seasonal cycles. Monet’s ability to embed such poetic nuance within a chromatic tapestry underscores his genius: color and light become vehicles for emotional depth as well as optical phenomena.

Monet’s Giverny Period and Artistic Evolution

Poppy Field belongs to a crucial phase in Monet’s Giverny tenure, when he oscillated between garden subjects—water lilies, the Japanese bridge—and open fields. Unlike the controlled compositions of his water-lily series, the poppy fields offered more complex color interplays and looser forms. This period also saw Monet refining his use of synthetic pigments—cadmium reds, chrome yellows, cobalt blues—that offered greater brilliance and permanence. Poppy Field thus represents both the culmination of his late 1880s experimentation with light and the precursor to his monumental water-lily panels of the early 20th century, wherein forms dissolve almost entirely into color rhythms.

Technical Analysis and Conservation Insights

Recent conservation studies of Poppy Field have illuminated Monet’s layered process. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) identifies cadmium-based reds and yellows as prominent pigments, reflecting Monet’s embrace of newer materials. Infrared reflectography reveals an underpainting in warm ochre, establishing a luminous ground for subsequent layers. Cross-sectional examination shows that the field’s poppy area comprises three to four layers: a warm underlayer, an intermediate green field tone, a broken overlay of red dabs, and final white highlights. Conservation efforts have addressed minor craquelure and varnish yellowing, restoring the painting’s original vibrancy and ensuring its chromatic integrity for future viewers.

Exhibition History and Critical Reception

When first exhibited in the 1890s, Poppy Field drew both praise and critique. Admirers celebrated its atmospheric realism and chromatic daring, noting how Monet captured the ineffable poetry of rural Normandy. Some academic critics, however, disapproved of its apparent sketchiness and lack of traditional finish. Over the decades, as Impressionism gained broader acceptance, the painting secured a place of honor in museum collections and retrospectives. Today, it is hailed as a quintessential example of Monet’s Giverny period and an enduring testament to Impressionism’s capacity to find profundity in ordinary landscapes.

Influence and Legacy

Poppy Field (Giverny) has influenced countless painters and art movements. Fauvist artists—Henri Matisse and André Derain—drew inspiration from Monet’s bold color juxtapositions and loose brushwork. Later, Color Field painters such as Mark Rothko acknowledged Monet’s role in elevating color relationships to primary compositional drivers. Plein-air and landscape artists continue to study Monet’s handling of light and atmosphere, seeking to emulate the immediacy and vibrancy of his technique. The painting’s legacy extends beyond art history into popular culture, where images of Monet’s poppy fields evoke nostalgia, serenity, and the transcendent power of nature.

Conclusion

In Poppy Field (Giverny), Claude Monet achieves a sublime fusion of sensory immediacy and poetic resonance. Through dynamic brushwork, a masterful palette of complementary hues, and unwavering plein-air dedication, he transforms a simple field of blossoms into a living celebration of summer’s light. The painting encapsulates the essence of mature Impressionism: a devotion to capturing transient effects, a rejection of rigid academic conventions, and a profound belief in nature’s power to move the soul. More than a study of color and form, Poppy Field endures as a timeless homage to beauty’s transience and the painter’s unceasing quest to illuminate the world in paint.