Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

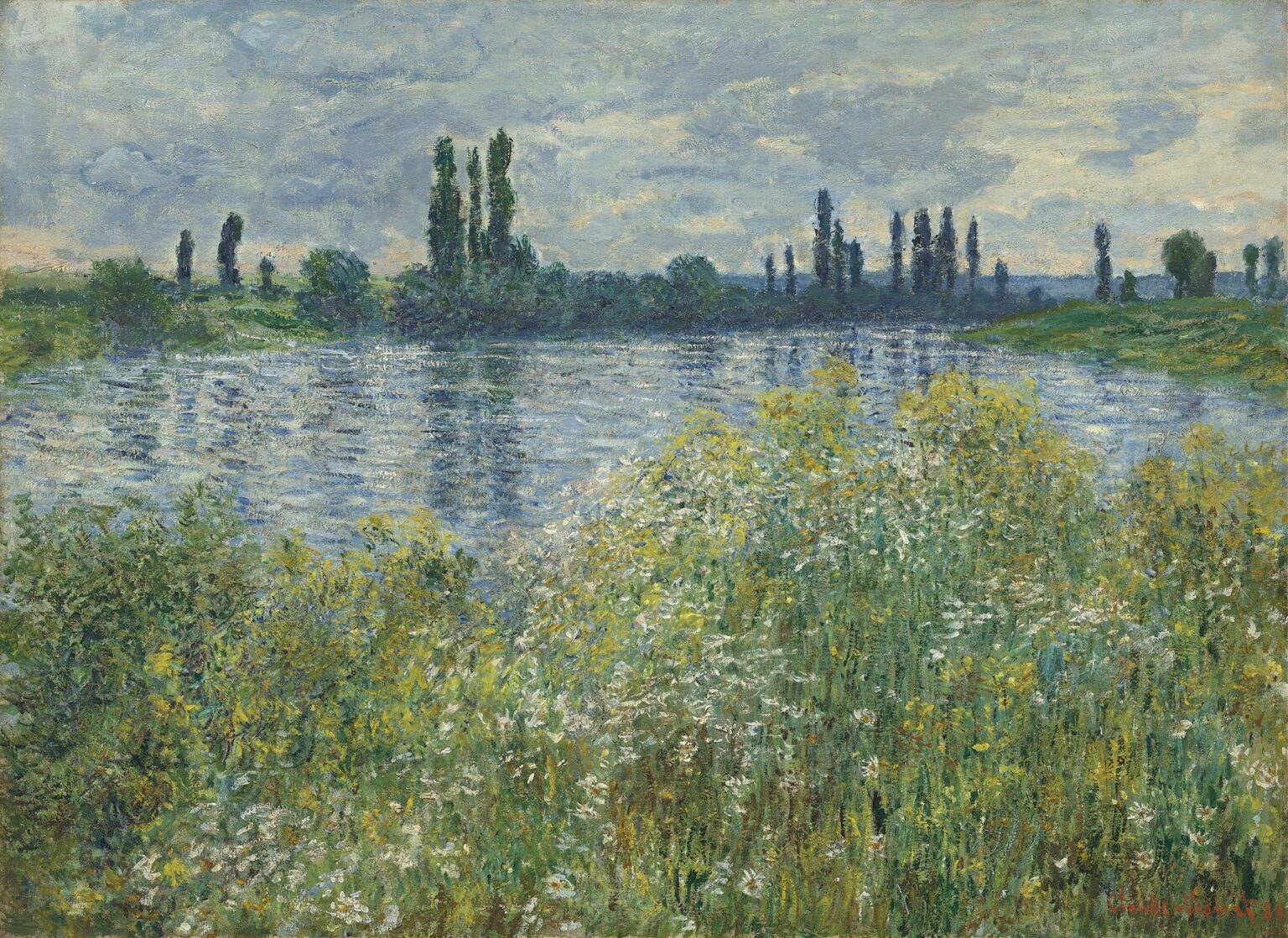

In Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil (1880), Claude Monet turns his gaze from the grand vistas of his famed water lily series to a more intimate riverside tableau. Here, he invites us to stand on the gentle slope of a Seine embankment at Vétheuil, a village west of Paris, where wildflowers and grasses mingle with the ever-changing currents of the river. Rather than depicting a heroic landscape, Monet frames an ordinary riverside scene—poppies, daisies, and yellow-green shrubbery in the foreground; the reflective Seine in the middle distance; and a distant line of poplar trees against a cloud-scudded sky. Through a symphony of color, fluid brushwork, and masterful manipulation of light, Monet transforms this commonplace view into a mesmerizing study of perception, atmosphere, and the ephemeral poetry of nature.

Historical and Personal Context

By 1880, Monet had endured personal hardships—financial struggles, the death of his beloved wife Camille in 1879, and the demands of raising two young sons. He sought solace and continuity in the village of Vétheuil, nestled along a tranquil bend of the Seine. The riverbanks here offered him both refuge and inspiration, serving as the backdrop for numerous canvases over a three-year residence. Unlike his more urban Argenteuil period, Vétheuil provided a setting where rural charm and pastoral serenity could coexist with the subtle hum of river traffic. In this climate of both grief and creative renewal, Monet’s paintings from 1880 radiate an emotional depth borne of personal reflection and artistic determination.

The Plein-Air Ethos

Monet’s method in the late 1870s and early 1880s epitomized the plein-air spirit central to Impressionism. Rejecting the confines of his Paris studio, he painted directly on-site, capturing the vagaries of light and weather as they unfolded. For Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil, he would have set up his easel on the grassy slope, confronting gusts of wind that tousled his canvas and flickering patches of sunlight that danced upon the water’s surface. This direct engagement with nature demanded swift, confident brushstrokes and a finely tuned color sense, enabling him to record the river’s shifting reflections and the dappled light filtering through clouds with immediacy and vitality.

Composition and Framing

Monet structures the composition around a broad horizontal sweep. The canvas divides naturally into three spatial bands: the flowering riverbank at the bottom, the shimmering water in the center, and the distant poplar line under a prismatic sky. The foreground occupies nearly half the picture plane, immersing viewers in the riot of wild blooms—greens, yellows, and whites interwoven in frenetic yet harmonious brushwork. This dense foreground anchors the composition and creates a tactile sense of place. In contrast, the middle band of the Seine offers a moment of calm, its horizontal strokes of blue and silver acting as a visual respite. Above, the vertical rhythm of poplar clusters guides the eye upward into a luminous sky painted with loose, swirling marks. Through this interplay of horizontal and vertical elements, Monet achieves a dynamic equilibrium that imbues the scene with both stability and movement.

Treatment of Light and Atmosphere

The central marvel of Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil lies in Monet’s orchestration of light. He deploys a high-key palette—pale blues, soft grays, tender greens, and sun-drenched yellows—to evoke the sensations of an overcast morning or late afternoon, when sunlight diffuses through a veil of clouds. The river’s surface becomes a conveyor belt for subtle tonal shifts: where cloud shadows pass, the water darkens to a slate-blue; where sunlight strikes, it gleams in scintillating ribbons of silver and white. The poplars, framed against the sky, appear as silhouettes at times and as luminous, leaf-studded forms at others, depending on how Monet modulates hue and contrast. This nuanced handling of light underscores the Impressionist credo that painting should capture not objects as fixed entities but the transient effects of light upon them.

Color Palette and Optical Mixing

Rather than relying on pre-mixed tones, Monet often applied pure pigments side by side, trusting the viewer’s eye to blend them at a distance. In the foreground, strokes of cadmium yellow sit adjacent to touches of cerulean blue and viridian green, generating a verdant luminosity that seems to vibrate. Small dashes of white and pink suggest daisies and other blossoms, infusing the bank with lively accents. On the water, flickering strokes of ultramarine mingle with lead white and faint rose to convey the river’s reflective qualities. In the sky, Monet layers cool grays, lavender-blue, and hints of pale ochre, allowing atmospheric perspective to register subtle depth. This technique of optical mixing not only heightens the painting’s vibrancy but also aligns with Monet’s belief that color interactions, rather than line or form alone, drive perceptual truth.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Monet’s brushwork in this painting exemplifies his mature Impressionist technique. In the foreground, he uses short, hooked strokes that pivot and overlap, evoking the tangled growth of wild flora. These strokes are layered in multiple directions, creating a textured tapestry that draws the viewer’s fingers toward the canvas surface. In the water band, he switches to broader, horizontal strokes, some lifted lightly to let the underpainting peek through, mimicking the undulating motion of the river. The poplar trunks and foliage receive vertical and swirling marks, suggesting the rustling of leaves in a gentle breeze. Even in the sky, Monet’s brushwork remains free and gestural: circular motions describe drifting cloud clusters, while quick horizontal dashes imply fleeting winds aloft. This varied application of paint renders the canvas itself a record of Monet’s physical engagement with his subject.

Spatial Depth and Perspective

Although Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil lacks strict linear perspective cues like converging roads or walls, Monet secures spatial depth through tonal attenuation and scale gradation. The wildflowers in the immediate foreground are rendered with dense, thick paint and vivid coloration, making them seem close enough to touch. The middle distance of the Seine appears comparatively smooth and calm, its reflective surface marking a broad, uninterrupted expanse. Beyond the river, the line of poplars recedes into a softer focus, their edges gently blurred by atmospheric haze. The sky, occupying nearly half the canvas, broadens the vista further, suggesting infinite space. Together, these strategies engage the viewer in a visual journey from the immediacy of the bank to the distant horizon.

Emotional Resonance and Psychological Underpinnings

Monet’s choice to depict a seemingly modest riverside scene carries an emotional, almost elegiac undercurrent. Painted not long after Camille’s death, the tranquil riverbank may have offered comfort and continuity in the face of personal loss. The painting exudes a meditative calm, as if each flicker of light upon the water were a moment of solace. The poplars, standing like silent sentinels, evoke both constancy and transience—ever-green but always swaying with the wind. In this sense, Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil resonates as an intimate reflection on mortality, memory, and the healing rhythms of nature. The viewer is invited to linger, to breathe in the morning air, and to sense the gentle lullaby of river and meadow.

Monet’s Work in Vétheuil and Legacy

Monet’s Vétheuil period (1878–1881) is less familiar to the general public than his Argenteuil and Giverny years, yet it represents a critical phase in his artistic evolution. Here, he honed his ability to portray light’s subtleties in more varied and rural contexts. Paintings like Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil paved the way for his later Giverny masterpieces, where his color palette would grow richer still. Moreover, this period solidified his reputation among fellow Impressionists, who recognized in Monet’s Vétheuil canvases a deepening mastery of atmosphere and color. The legacy of these works extends beyond art history: they continue to influence contemporary landscape painters and to captivate audiences with their blend of technical daring and emotional sincerity.

Conservation and Technical Studies

Modern conservation efforts on Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil have revealed details of Monet’s layered technique. X-ray fluorescence analysis shows that he built the canvas in successive passages: a warm ground layer of ochre underlies the green bank, while cooler whites form the river’s reflective surface. Infrared imaging uncovers compositional adjustments—slight shifts in the placement of poplars that suggest Monet’s willingness to refine his vision on the spot. Microscopic cross-sections indicate that the paint was applied wet-on-wet in many areas, requiring Monet to work swiftly before earlier layers dried. These findings underscore his dedication to capturing immediate impressions and provide invaluable insights into his creative process.

Cultural and Social Reflections

In depicting a rural bank rather than an aristocratic garden or a grand château, Monet aligns with the Impressionist impulse to democratize art’s subjects. The wildflowers and modest poplar groves speak to a universal, accessible beauty—one that belongs not to the privileged few but to anyone who steps outside to breathe fresh air. This egalitarian ethos resonated with contemporary viewers amid rapid industrialization and urban growth, reminding them of nature’s enduring power to restore the human spirit. Today, Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil continues to serve as a visual reminder of the importance of preserving natural landscapes in the face of modern development.

Conclusion

Through Banks of the Seine, Vétheuil, Claude Monet transforms a simple riverside view into a rich tapestry of light, color, and emotion. His intuitive brushwork, high-key palette, and layered compositional structure invite viewers into a sensory experience that balances immediacy with introspection. Painted during a period of personal upheaval, the work offers both a testament to Monet’s enduring artistic vision and a meditation on nature’s quiet consolations. Over a century later, the canvas endures as a masterful example of Impressionism’s capacity to elevate the commonplace into poetry, reminding us that every riverbank, every morning mist, and every wildflower harbors the promise of transcendence.