Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

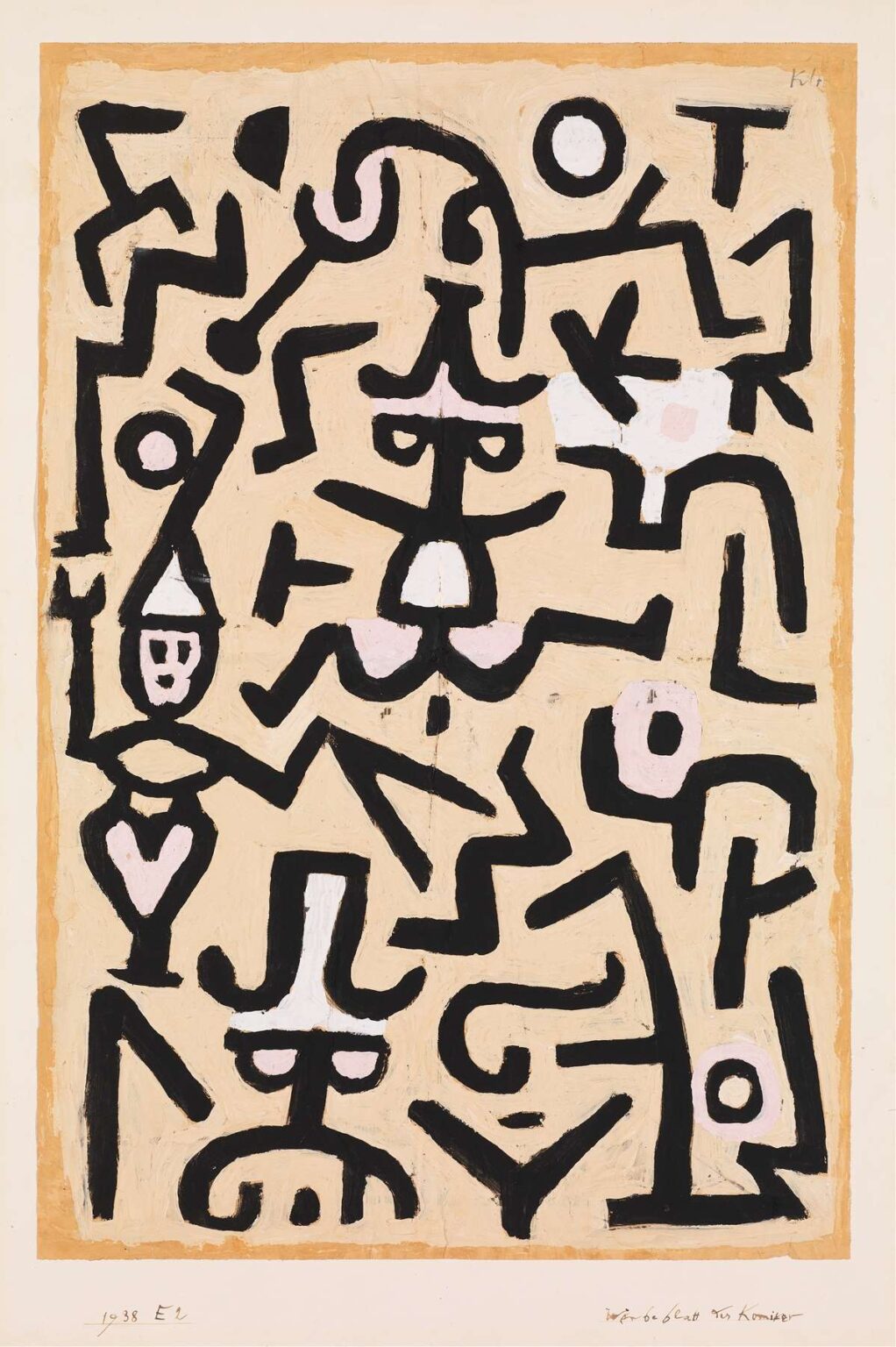

In Comedians’ Handbill (1938), Paul Klee channels the spirit of performance and play into a dynamic tapestry of gestural signs and rhythmic patterns. Rather than depicting a literal poster for a stage troupe, Klee abstracts the essence of comedy—its energy, its masks, its interplay of figures—into bold black lines set against a warm, flesh-toned ground. The result is a visual “handbill” that announces not specific actors or dates, but the very idea of the comic spectacle. Executed in oil and pastel on paper, this work exemplifies the late style of an artist who continually reinvented his vocabulary, marrying primitivist iconography with surreal improvisation. Over the course of this analysis, we will explore how Comedians’ Handbill synthesizes theater, mythology, and modernist abstraction into a singular visual ode to laughter and intrigue.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1938, Klee’s health was deteriorating under the weight of a debilitating scleroderma diagnosis, yet his creative drive remained undiminished. The political climate in Europe had grown increasingly oppressive, with the rise of totalitarian regimes that tolerated little dissent or levity. In this context, Klee’s homage to the comedian takes on added resonance: it celebrates the liberating power of humor even as the world veers toward tragedy. Moreover, his association with the Bauhaus had ended years earlier with the school’s closure in 1933. Now teaching at Düsseldorf and later at Zurich’s Kunstgewerbeschule, Klee turned inward, focusing on the elemental forces of line, color, and symbolic form. Comedians’ Handbill emerges from this period as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the artist’s unwavering commitment to creative play.

Theatricality and the Comic Archetype

Klee’s painting does not present a narrative scene but rather conjures the aura of the theater through abstracted motifs. One perceives hat shapes reminiscent of clowns’ caps, zigzagging lines suggesting prancing legs, and oval forms that recall juggling balls. Faces appear only as minimal masks—two dots for eyes, a simple curve for a mouth—yet these sparing features carry an unmistakable expression of bemusement or mischief. By reducing theatrical elements to their graphic essence, Klee invites viewers to mentally supply the performance, the laughter, the audience’s applause. The work thus functions as a meta-poster: it advertises the very act of comedy rather than any specific company or show.

Compositional Dynamics and Spatial Ambiguity

At first glance, Comedians’ Handbill reads as a dense network of black strokes floating atop a creamy-beige stretcher. A narrow border of muted ochre frames the scene, like the proscenium arch surrounding a stage. Within this frame, thick, calligraphic lines meander, intersect, and coil, creating negative pockets painted in pale pink and white. These color interruptions punctuate the visual field, suggesting spotlights or bursts of applause. The lines form ambiguous shapes—an angular torso, a curved arm, a suspended sphere—yet none resolves fully into a figurative silhouette. Perspective is absent; instead, Klee flattens dollops of black pigment into a shallow pictorial plane that hums with potential movement. The eye roams freely, tracing the energetic contours as if following dancers in a variegated carnival.

Color Harmony and Textural Contrast

Unlike many of Klee’s earlier works of chromatic subtlety, Comedians’ Handbill relies on a restrained, high-contrast palette: dense black lines, a singular ground color, and sporadic pastel inlays. The ground’s warm beige carries hints of peach and apricot, evoking flesh or stage makeup. Against this backdrop, the black lines assume a theatrical flair, akin to stage makeup outlines that transform the actor’s face. The pale pink washes—deployed sparingly in mask-like shapes—suggest the flush of laughter or the rosy glow of footlights. Klee’s handling of paint is exuberant yet controlled: the black strokes vary from thick impasto to dry brush, revealing glimpses of the underlayer. This tactile variation underscores the work’s physicality, as if the very surface vibrates with comedic energy.

Line as Gesture and Musicality

Central to Klee’s artistic philosophy was the idea that line functions like a musical note: it carries rhythm, inflection, and tone. In Comedians’ Handbill, the black strokes form an erratic, syncopated rhythm across the canvas. Some lines snap in sharp angles—staccato movements of a pantomime—while others curve languorously, reminiscent of a comedic flourish or a dancer’s bow. Intersecting paths create visual “accents,” moments of dramatic punctuation that mimic laughter’s sudden bursts. The pastel shapes act like rests in a musical score: brief silences that heighten the impact of the surrounding lines. Through this analog of drawing-as-composition, Klee transforms the static painting into a visual fugue, each gesture echoing the next in playful counterpoint.

Symbolism and the Role of the Mask

Masks occupy a special place in Klee’s imagery, serving as portals between the self and mythic archetype. In ancient theater, masks amplified expression and allowed actors to assume multiple roles. In Comedians’ Handbill, Klee employs mask-like ovals with dots for eyes, floating within the labyrinth of lines. These masks appear simultaneously impassive and expressive—at once the joker’s smile frozen in time and the spectator’s questioning stare. The masks’ minimal features underscore Klee’s belief that a few strokes can capture the essence of emotion. Their presence imparts a sense of mystery: are we witnessing the players themselves, the audience’s gaze, or the artist’s own self-reflective alter ego, winking through the painted surface?

Technical Innovation and Layered Technique

Klee’s late technique in Comedians’ Handbill demonstrates his mastery of mixed media. Starting with a paper support primed in a warm ground, he sketched initial line diagrams with thin charcoal or graphite. Over this, he applied a thin wash of beige oil paint, creating a uniform field. Next, he executed the black outlines in impasto oil, using a flat brush loaded heavily with pigment. The thick strokes leave ridges and valleys, adding sculptural relief to the paper. When these dried, Klee filled in select areas with pastel or diluted gouache in pale pink and white, integrating them into the black network. Finally, rough dabs of ochre around the perimeter frame the composition. The layering of opaque and semi-transparent media gives the work depth and complexity, revealing traces of earlier marks beneath the final surface.

Relationship to Klee’s Concept of “Taking a Line for a Walk”

In lectures later compiled as the Pedagogical Sketchbook, Klee famously described the line as “a dot going for a walk.” Comedians’ Handbill exemplifies this concept: the black lines wander freely across the “stage,” unbound by representational constraints. Each stroke follows its own logic, yet collectively they form an undeniable coherence. The line’s freedom mirrors the comedian’s improvisational spirit, where each audience reaction can alter the performer’s path. By allowing the line to roam, Klee captures the essence of comedy: its unpredictability, its rhythmic timing, and its capacity to transform everyday gestures into art.

Comparative Analysis within Klee’s Later Oeuvre

Painted late in Klee’s career, Comedians’ Handbill shares affinities with works such as Highways and Byways (1938) and Senecio (1922) in its graphic economy and stylized mask forms. Yet it is unique in its explicit theatrical allusion and poster-like format. Unlike the dreamy abstractions of the mid-1930s or the cellular patterns of Ad Parnassum (1932), this piece foregrounds dramatic gesture and narrative suggestion. It anticipates later developments in abstract expressionism and graffiti art, where calligraphic marks and monumental line figures would dominate. Klee’s playful spirit and mastery of line continue to inspire artists who seek to fuse spontaneity with structural ingenuity.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Open-Endedness

True to Klee’s vision of art as a “living thing,” Comedians’ Handbill resists a singular meaning. Viewers may see a procession of jesters, a carnival of masks, or a coded language of signs. The lack of literal depiction encourages active interpretation: one might imagine the comedian’s next quip, the audience’s laughter, or the backstage preparations behind the curtain. The work’s dynamism invites the eye to dance across the surface, eliciting personal associations and emotional responses. In this way, Klee transforms the painting into a participatory experience, where meaning is co-created by artist and observer.

Legacy and Influence

Comedians’ Handbill occupies a unique place in modern art history. Its fusion of primitivist mask forms, calligraphic abstraction, and performative themes anticipated postwar explorations in action painting and conceptual art. Artists such as Cy Twombly and Jean-Michel Basquiat echoed Klee’s exuberant line work and symbolic fragments in their own gestural pieces. Graphic designers in the mid-twentieth century drew on Klee’s poster-like compositions to craft advertisements that balanced whimsy and abstraction. The painting’s emphasis on the performative potential of line continues to inform contemporary practices in installation, performance art, and digital animation.

Conservation and Exhibition

As a mixed-media work on paper, Comedians’ Handbill demands specialized care. The heavy oil strokes can crack over time if humidity fluctuates, while the pastel inlays are vulnerable to abrasion. Museums housing the piece maintain stable climate control and display it behind UV-filtering glass. Infrared imaging has uncovered earlier underdrawings, showing how Klee adjusted his composition as he worked—erasing certain lines, introducing new gestures, and refining the balance between positive and negative space. Recent exhibitions have placed the painting alongside historical clown ephemera, highlighting its dialog with popular entertainment culture and reinforcing its handbill-like character.

Conclusion

Paul Klee’s Comedians’ Handbill (1938) stands as a vibrant testament to art’s capacity to capture laughter, disguise, and the theatrical pulse of human imagination. Through bold black contours, a warm ground, and touches of pastel, Klee constructs an abstract carnival that both honors ancient mask traditions and embraces modernist freedom. The painting’s rhythmic energy, symbolic depth, and formal inventiveness ensure its place among the artist’s most compelling late works. In celebrating the comedian’s art, Klee celebrates art itself: a performance of line and color that continues to enchant, provoke, and inspire audiences across generations.