Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

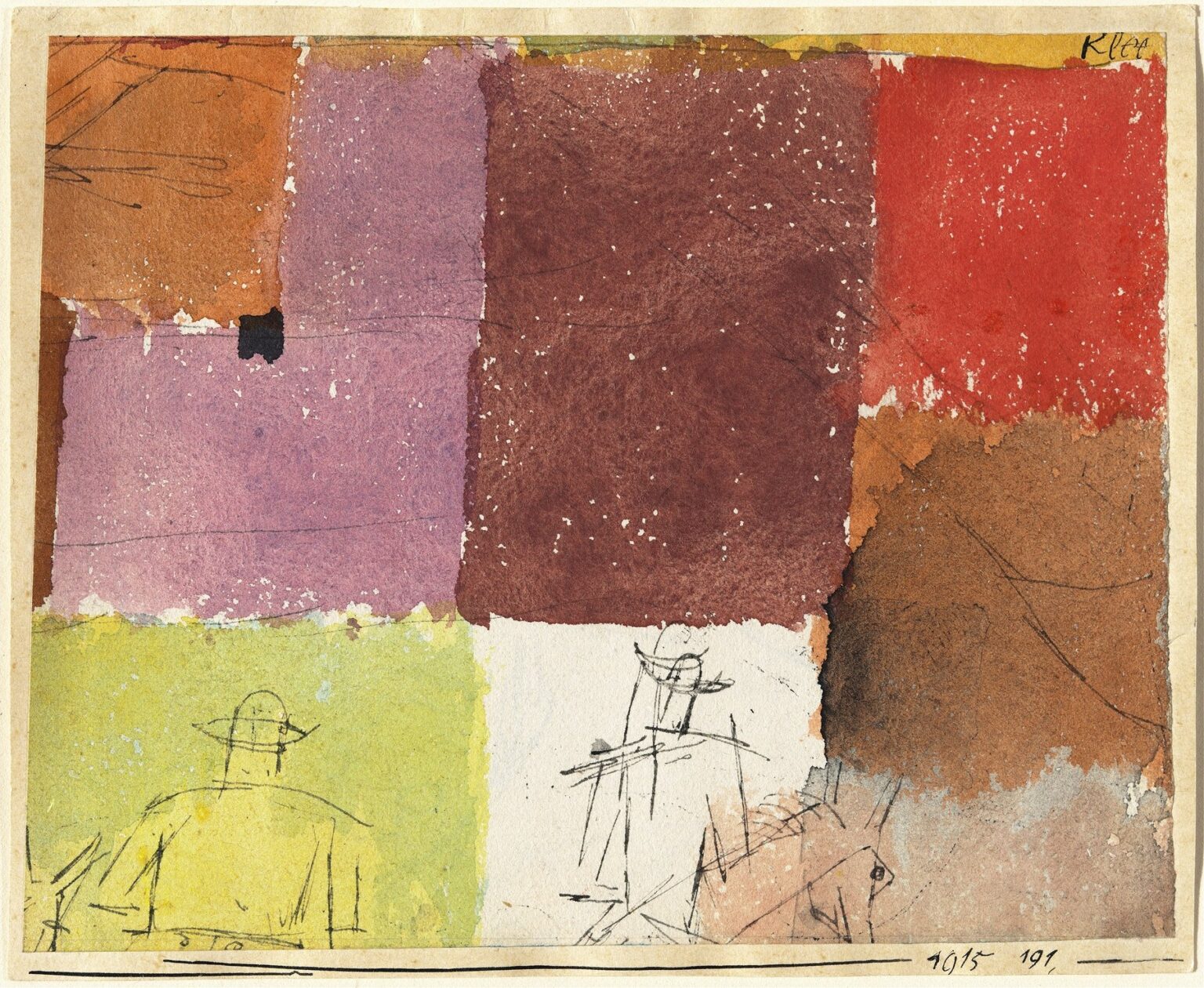

Paul Klee’s Composition with Figures (1915) stands at the threshold of his lifelong exploration of abstraction, symbolism, and the interplay between line and color. Painted during the turbulent years of World War I, this deceptively simple collage-like arrangement of colored rectangles, pencil sketches, and indistinct figurative marks reveals Klee’s burgeoning interest in the modernist reinvention of form. By overlaying rudimentary human shapes onto geometric grounds, Klee hints at the tension between the earthly and the transcendent, the concrete and the imagined. This analysis examines the painting’s historical context, compositional strategies, color theory, symbolic resonances, technical methods, and its place within Klee’s evolving oeuvre.

Historical Context and Artistic Climate

In 1915, Europe was engulfed in the First World War, and many artists confronted the crisis by abandoning traditional representation in favor of abstraction or spiritual symbolism. Paul Klee, having exhibited with the Blaue Reiter group in Munich, was influenced by Wassily Kandinsky’s ideas of spiritual expression in art and by the raw energy of Expressionism. At the same time, Cubism’s fragmentation of form and interest in multiple viewpoints resonated across the avant-garde. Klee himself had a background in music, which informed his concept of “visual music”—the notion that art could compose rhythms and harmonies in color and line much like a symphony. Composition with Figures emerges from this dynamic milieu as an experiment in balancing structural order with the spontaneity of drawing.

Formal Structure and Spatial Ambiguity

The canvas is divided into six roughly equal rectangles—three along the top and three along the bottom—each rendered in a distinct, subtly textured hue. The top row presents earthy ochre at left, dusty lavender in the center, and deep russet at right. Below, a pale chartreuse rectangle occupies the left, a bleached ivory at center, and a muted terracotta on the right. These colored grounds function like stage flats or architectural facades, establishing a grid that organizes the painting. Yet this rigid geometry is immediately undercut by the freehand pencil sketches that traverse the boundaries between rectangles, introducing human silhouettes and gestural marks that refuse to remain confined. Perspective collapses as figure and ground interchange roles, leaving the viewer in a space both ordered and unsettled.

Color Harmonies and Emotional Tonality

Klee’s choice of palette in Composition with Figures is remarkable for its understatement. Rather than employing primary contrasts, he favors near-neighboring hues that resonate softly: the ochre slides into the brown, the lavender bridges toward the terracotta, and the chartreuse offers a counterpoint to the browns without jarring the eye. This muted harmony evokes early spring sunlight filtering through haze or the patina of weathered fresco—images of transformation and decay fitting for an artist grappling with war’s devastation. Small flecks of white pigment appear across the surface, as if the paint itself has chipped away, lending the work a timeworn texture. Through this careful modulation of tone, Klee conveys both warmth and weariness, suggesting that beneath the painterly surface lies an undercurrent of human fragility.

Line, Gesture, and the “Walking Point”

At the heart of Klee’s theoretical framework lies his assertion that “a line is a point going for a walk.” In Composition with Figures, the pencil lines wander freely across the color fields, sketching crude humanoid forms: a head crowned by a simple curved line, a torso suggested by two slanting strokes, stick-like limbs. These figures are not anatomical studies but fleeting traces—ghosts of human presence whose gestures register time, movement, and emotion in a few spare marks. In one corner, a reclined figure appears to merge with the ground, while at center, upright shapes hint at dancers or sentinels. The pencil’s graphic immediacy contrasts with the painted rectangles’ solidity, creating a dialogue between the ephemeral and the enduring.

Symbolic Resonances of the Human Figure

Though abstract in execution, Composition with Figures carries symbolic weight through its figural allusions. The crudely drawn silhouettes evoke childhood doodles, primal cave paintings, and the most rudimentary hieroglyphs. Klee was fascinated by the art of children, believing that their unselfconscious marks tapped into a universal visual language. Here, the child-like figures serve as archetypes of human existence—humble and vulnerable within the larger matrix of colored fields. The gridded structure may represent societal order, while the figures embody the individual spirit striving for expression. This tension between collective structure and personal gesture speaks to the broader human condition, especially poignant in the shadow of global conflict.

Materiality and Painterly Technique

Composition with Figures is executed in watercolor, gouache, and pencil on heavyweight paper mounted to canvas. Klee likely applied the colored rectangles as flat washes, allowing pigments to pool and granulate at the edges. In some areas, the paint appears scraped or rubbed away, revealing the white ground beneath—a technique he used to evoke age and material complexity. Once the washes dried, Klee introduced the small white speckles by flicking or spattering paint, further enhancing the illusion of surface erosion. The final step involved drawing the figures and gestural lines in soft graphite or charcoal, the marks ranging from delicate scribbles to more assertive strokes. This layering of media—transparent wash, opaque gouache, pastel-like matte—yields a rich tapestry of textures that both conceals and reveals the painting’s process.

Relationship to Klee’s Theoretical Writings

In his later Pedagogical Sketchbook, Klee emphasized the interplay of improvisation and structure, of the “inner necessity” guiding each mark. Composition with Figures embodies these principles: the grid of color fields provides the structural framework, while the freehand figures and splattered flecks introduce improvisational vitality. Klee believed that art should embody the “ascent to the spiritual,” and here that ascent is mapped in the rising gestures of stick figures and the upward sweep of diagonal lines. Color, for Klee, was akin to musical harmony; the muted yet varied palette in this work could be likened to a melancholic nocturne, with its subtle dissonances and gentle resolutions.

Comparative Context within Klee’s Oeuvre

1915 marked a prolific period for Klee. Works such as The Twittering Machine and Angelus Novus also explored the tension between whimsical imagery and ominous undertones. However, Composition with Figures is distinctive in its explicit grid structure, foreshadowing the pointillist virtuosity of Ad Parnassum (1932) and the cellular abstractions of Polyphony (1932–34). The marriage of geometric partition and spontaneous line here can be seen as a laboratory for ideas that would later crystallize into Klee’s mature style. Unlike pure abstractionists who dispensed with representation entirely, Klee maintained a poetic link to the human figure, ensuring that even his most abstract works resonated with the human spirit.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Openness

Klee’s Composition with Figures does not offer a single narrative; instead, it beckons viewers into a space of contemplation and discovery. One might first notice the interplay of color blocks, then uncover the faint silhouettes and their interconnections. Are the figures interacting, dancing, or merely floating alone? Does the grid imprison or protect them? Such questions engage the viewer in an ongoing dialogue with the painting, making each encounter unique. The open-endedness of Klee’s symbolism ensures that the work remains fresh and resonant, accommodating new interpretations as individual viewers bring their own memories and emotions to the experience.

Legacy and Influence

Composition with Figures has influenced generations of artists interested in the boundary between abstraction and figuration. The use of grid structures populated with gestural marks can be traced in the work of mid-century Abstract Expressionists like Adolph Gottlieb and later in Post-Abstractionists who reintegrated figurative elements. In contemporary art, echoes of Klee’s method appear in works that mix digital pixelation with hand-drawn gestures, underscoring the timeless appeal of his pioneering synthesis of order and spontaneity.

Conservation and Exhibition History

As a mixed-media work on paper, Composition with Figures demands careful preservation. The watercolor and gouache layers are vulnerable to humidity fluctuations, while graphite marks can smudge if not properly protected. Museums housing the piece display it in low-light conditions with stable humidity, often using UV-filtering glazing. Recent technical analyses, including infrared reflectography, have revealed preliminary pencil sketches beneath the color fields, confirming Klee’s practice of drawing directly onto the ground and adjusting composition as the work progressed.

Conclusion

Paul Klee’s Composition with Figures (1915) captures a moment of transition—historically, artistically, and personally. Through a simple arrangement of colored rectangles and spontaneous pencil marks, Klee grapples with the fundamental questions of modern art: How do we balance structure and freedom? In what ways can abstraction carry the essence of human presence? By integrating geometric order with child-like figures, Klee forges a unique visual language that continues to speak to viewers over a century later. His painting remains a testament to the power of minimal means to evoke maximal significance, encouraging us to find wonder in the interplay of line, color, and form.