Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to “Adam and Little Eve”

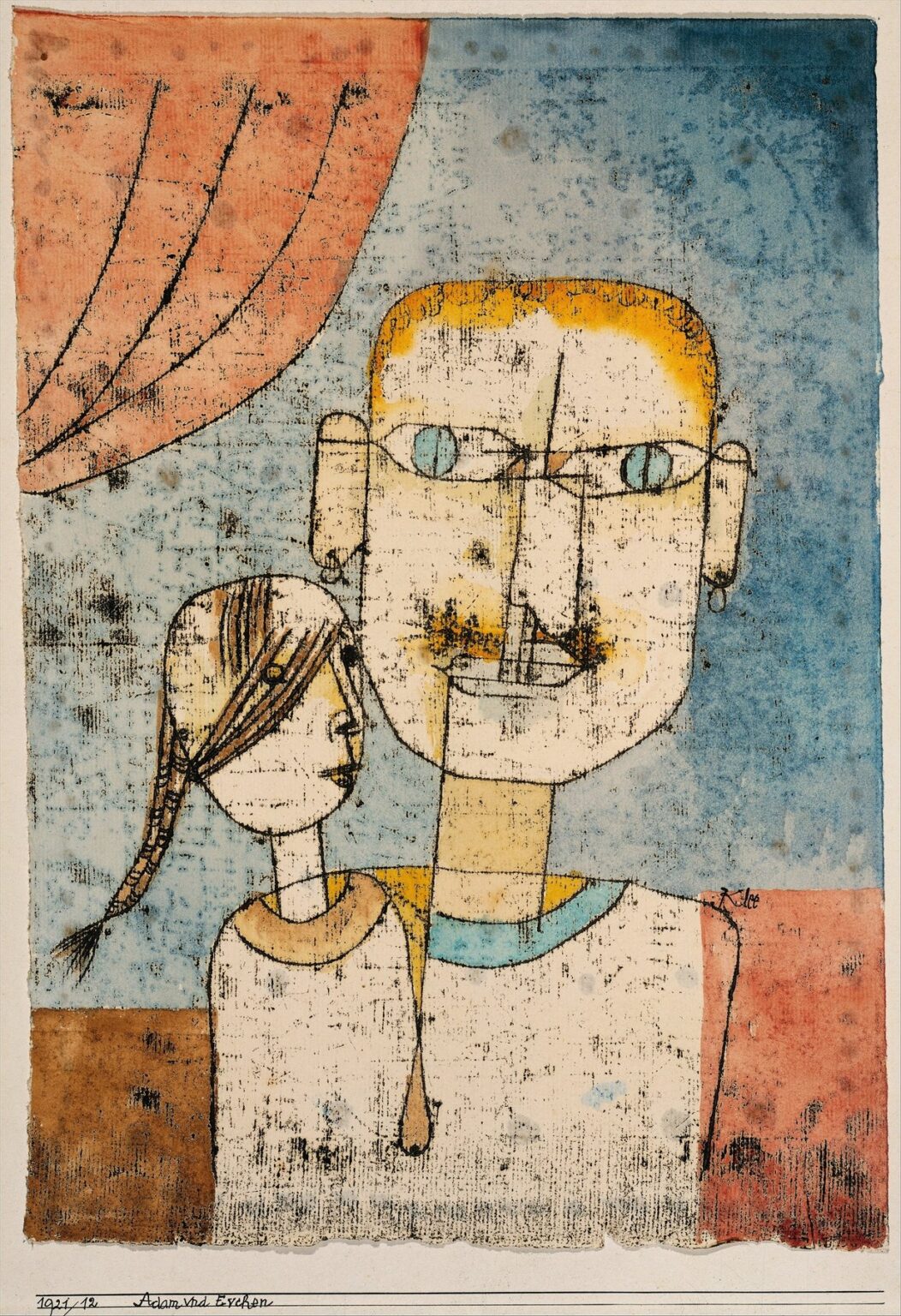

Paul Klee’s 1921 painting Adam and Little Eve offers a delicate yet profound meditation on origins, identity, and the bonds between parent and child. Situated at a pivotal moment in Klee’s career—shortly after joining the Bauhaus faculty—the work blends figurative suggestion with the artist’s trademark abstraction. At first glance, two stylized figures occupy a flattened pictorial space defined by soft washes of color and a tapestry of fine, sketch-like lines. The larger form, interpreted as Adam, gazes outward with an expression of quiet contemplation, while a smaller, childlike figure—Little Eve—nestles close by. Through careful composition, color harmonies, and subtle symbolism, Klee transforms a biblical narrative into a universal exploration of human connection.

Historical Context and Klee’s 1921 Oeuvre

In the early 1920s, Europe was still reeling from the aftermath of World War I, and the Bauhaus school in Weimar sought to renew creative practice by integrating art, craft, and design. Klee joined the Bauhaus faculty in 1921 alongside Wassily Kandinsky, bringing a unique perspective shaped by travels in Tunisia, studies of folk art, and early Expressionist collaborations. His works from this period often fuse playful formal experiments with deeper philosophical questions. Adam and Little Eve emerges from this climate of innovation, reflecting Klee’s interest in primitive imagery, children’s drawings, and the search for elemental forms. It stands alongside other 1921 pieces—such as Mother and Child, Two Men Meet in the Street, and Insula dulcamara—in its exploration of human figures through simplified means.

Formal Composition and Spatial Arrangement

Klee arranges his composition with a balance of symmetry and gentle asymmetry. The two figures dominate the foreground, their torsos occupying the lower half of the canvas, while a broad swath of pale blue rises behind them like a sky. Above this, a rectangular red form in the upper left suggests a draped curtain or architectural element, hinting at an enclosed space. The larger figure’s head tilts slightly to the right, guiding the viewer’s eye toward the smaller head of Little Eve. Horizontal and vertical strokes—some echoing measurement marks—create a subtle grid that underpins the loose figuration. This interplay of geometric structure and organic line typifies Klee’s capacity to unify spontaneity with compositional rigor.

Line Quality and Gestural Drawing

At the heart of Adam and Little Eve lies Klee’s mastery of line. He employs a fine-tipped pen or brush to trace the contours of faces, torsos, and limbs with an economy of strokes. Facial features are rendered through vertical and horizontal hatches, resembling a technical diagram or schematic. The heads—oversized relative to their bodies—carry elongated necks, emphasizing the act of looking and listening. The line work brims with both precision and lyricism: a single curving stroke defines the shoulder, while multiple parallel lines sketch the smaller figure’s hair in simplified braids. These gestures reveal Klee’s belief that drawing is a form of expressive notation, capable of conveying both form and psychological nuance.

Color Palette and Symbolic Tonality

While Klee often embraced vibrant palette experiments, Adam and Little Eve employs a restrained color scheme that enhances its emotional resonance. The larger figure’s hair is brushed in a warm ochre, subtly highlighting the skullcap shape. Skin tones emerge from delicate washes of off-white and pale pink, allowing the underlying paper texture to suggest flesh without heavy modeling. The child’s hair and the background’s sky-blue are similarly applied in thin, translucent layers, conveying an airy, dreamlike atmosphere. The red rectangle—in contrast to these muted hues—injects a note of warmth and grounding, perhaps alluding to the earth or a hearth-like presence. Overall, the palette balances cool and warm tones, evoking both intimacy and distance.

Depiction of Figures: Adam and Little Eve

Klee’s interpretation of Adam and his daughter—or “Little Eve”—eschews literal biblical representation in favor of archetypal silhouettes. Adam’s broad shoulders and rectangular torso suggest strength and stability, while the slight curve of his mouth and the vertical hatch across his eyes hint at introspection. Little Eve, by contrast, appears fragile and inquisitive: her head is smaller and more circular, her neck slender, and her gaze turned toward her father. The proximity of their forms—Eve’s profile nearly touching Adam’s cheek—speaks to dependency and affection. Yet the two figures remain distinct entities, their outlines never fully merging, emphasizing both unity and individuality within familial bonds.

Expression and Psychological Depth

Despite the painting’s apparent simplicity, Klee imbues his subjects with a rich emotional subtext. Adam’s direct, almost schematic gaze confronts the viewer, inviting questions about responsibility, protection, and the burden of guardianship. Little Eve’s turned profile conveys curiosity and reverence, capturing the child’s implicit trust. The absence of overt narrative details—no garden, no serpent—shifts the focus inward to the psychological interplay. Viewers sense a timeless exchange: a moment suspended between innocence and awareness, autonomy and dependence. Klee’s abstracted faces thus function less as portraits and more as universal symbols of relational dynamics.

Use of Geometric Abstraction

Though rooted in figuration, Adam and Little Eve employs geometric abstraction to reinforce thematic content. The rectangular red form in the upper left, the grid lines behind the figures, and the simplified shapes of torsos and heads recall architectural and mathematical diagrams. These geometric elements ground the figures within a constructed space, suggesting that relationships—like buildings—are built on foundational frameworks. At the same time, the harmonious alignment of forms and the rhythmic repetition of lines create a visual melody, akin to musical counterpoint. Through this blend of geometry and organic line, Klee demonstrates that abstraction can serve both structural and expressive ends.

Symbolism and Biblical Allusion

While Klee’s painting does not depict Edenic flora or fauna, its title and central figures evoke the Genesis narrative. “Adam and Little Eve” suggests a reimagining of the original couple’s story through a modern lens—one that focuses not on fall from grace but on the continuity of life through offspring. The absence of a female Adam partner and the introduction of a child figure hint at themes of lineage and rebirth. The red rectangle might symbolize both knowledge (as the forbidden fruit) and unconditional love (as a hearth fire). Klee’s sparse symbolism invites multiple readings, encouraging viewers to project personal and cultural associations onto these universal archetypes.

Materiality and Techniques

Klee executed Adam and Little Eve in watercolor and pen on prepared board or heavyweight paper. His technique begins with a light pencil framework, followed by pen and ink line work to define forms. Watercolor washes are then applied over or under these lines, creating areas of soft color that interact with the underlying hatch marks. The paper’s tooth shows through, contributing to the image’s textured patina. Subtle erasures and reworkings—visible in faint ghost lines—reveal Klee’s iterative process: he often returned to make adjustments, balancing spontaneity with refinement. The result is a work that retains the freshness of a sketch while achieving the depth of a finished painting.

Klee’s Pedagogical and Philosophical Influences

As a Bauhaus instructor, Klee developed theories on form, color, and teaching that emphasized art as a language. His Pedagogical Sketchbook codified principles such as the importance of line, rhythmic balance, and unity through contrast. Adam and Little Eve can be seen as a practical embodiment of these ideas: the line carries meaning, color unifies, and every mark contributes to the whole. Philosophically, Klee was influenced by anthroposophy and the writings of Goethe, which championed the spiritual dimension of art. By abstracting a biblical motif into elemental forms, he bridges these intellectual currents, proposing that art can reveal spiritual truths through material gestures.

Interaction of Figure and Ground

Klee’s handling of figure-ground relationships in Adam and Little Eve exemplifies his nuanced spatial awareness. The pale blue background recedes, while the red rectangle and ochre hair highlight advance, creating subtle depth without traditional perspective. The wash extends over the figures’ edges in places, integrating them into the environment. At the same time, the dark pen lines define separation, ensuring that forms remain legible. This interplay underscores the dynamic tension between subject and setting: Adam and Little Eve are both contained by and emergent from their pictorial world. The technique illustrates Klee’s belief in permeable boundaries between form and space.

The Role of Scale and Proportion

In Klee’s figurative works, proportions often shift to convey meaning. Here, Adam’s head is disproportionately large relative to his shoulders, emphasizing intellectual or spiritual dimensions. Little Eve’s smaller scale suggests youth, vulnerability, and burgeoning awareness. The rectangular red element looms above them like a shelter or canopy, its size balancing the composition. These intentional distortions reflect Klee’s conviction that scale is a tool of expression rather than mere replication of reality. By altering proportions, he directs emotional focus and creates a poetic rather than documentary image.

Reception and Legacy

While Paul Klee gained modest recognition during his lifetime, modern scholarship has elevated Adam and Little Eve as a fine example of his mid-career synthesis of figuration and abstraction. Exhibited in retrospectives of Bauhaus works and in thematic shows on mythic imagery, the painting is often cited for its refined economy of means and psychological subtlety. Graphic designers, illustrators, and contemporary artists continue to draw inspiration from Klee’s method of integrating line and wash. The work’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to speak across contexts—religious, psychological, and aesthetic—without prescribing a single interpretation.

Conclusion

“Adam and Little Eve” encapsulates Paul Klee’s genius for forging universal narratives from elemental forms. Through a balanced interplay of line, color, and geometry, he transforms a biblical allusion into a timeless exploration of human bonds. The painting’s deceptively simple surface—sketch-like lines, pale washes, and a bold red form—masks a complex web of symbolism, pedagogical insight, and emotional depth. Nearly a century after its creation, Adam and Little Eve continues to resonate, reminding viewers that art can distill the most profound human experiences into a few thoughtful strokes.