Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Cultural Context of 1909

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Europe stood at the intersection of profound religious questioning and artistic innovation. While traditional Christian iconography continued to inform much of the continent’s cultural life, painters and writers were simultaneously exploring new modes of expression drawn from Symbolism, Modernism, and the burgeoning currents of psychological introspection. In Poland, partitioned and politically fractured, artists like Jacek Malczewski (1854–1929) navigated national identity, myth, and spirituality with particular urgency. By 1909, Malczewski had emerged as Poland’s leading Symbolist painter, reconciling Christian themes with personal allegory and philosophical depth. His Christ in Emmaus thus operates at the confluence of Biblical tradition and the Symbolist conviction that the visible world points toward hidden realities.

Jacek Malczewski’s Artistic Vision

Trained in Warsaw and Munich and influenced by Jan Matejko’s historical grand manner, Malczewski distinguished himself by infusing narrative scenes with poetic allusion. He embraced Symbolist tenets—mystery, metaphor, interior vision—while retaining technical rigor drawn from academic practice. Malczewski’s oeuvre oscillates between explicitly patriotic subjects and deeply spiritual works, often merging the two in layered allegories. Christ in Emmaus exemplifies his mature approach: the familiar Gospel account becomes a vehicle for exploring themes of revelation, hospitality, and the transformative power of sacred encounter. Here, Malczewski transcends mere illustration to propose that the Eucharistic moment is both historical event and perennial spiritual possibility.

The Biblical Narrative and Its Symbolism

The story of Christ’s appearance in Emmaus (Luke 24:13–35) recounts how two disciples, disheartened by the Crucifixion, encounter the risen Jesus on the road but fail to recognize him until he breaks bread with them. That moment of recognition transforms sorrow into joy. Malczewski’s painting captures this Eucharistic epiphany, emphasizing the breaking of bread as sacrament and symbol of communal unity. Through his handling of light, composition, and gesture, he conveys the profound shift from spiritual blindness to insight. In Malczewski’s hands, Emmaus becomes not only the site of a singular Gospel miracle but also a universal locus of encounter—where the divine hidden in the ordinary is unveiled through sincere hospitality.

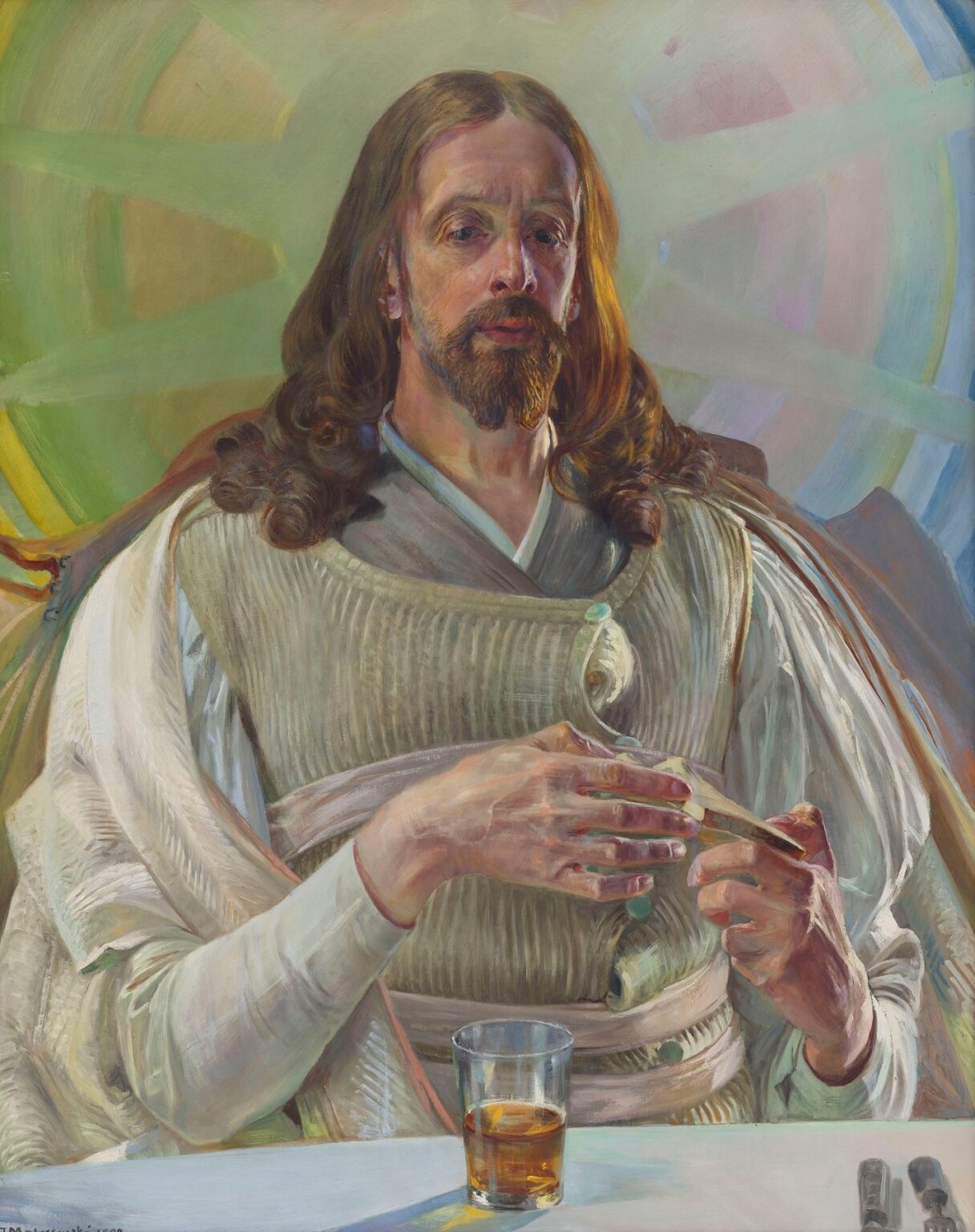

Composition and Spatial Arrangement

Malczewski structures the canvas around a low, luminous table that anchors the composition in the foreground. Christ sits centrally, elevated on a raised bench or throne-like chair that suggests both royal dignity and priestly function. His right hand breaks the loaf, fingers splayed in a gesture of blessing, while his left hand holds a small knife or implements for cutting. Flanking him are the two disciples, one standing and leaning in, the other seated or kneeling, each caught between motion and stillness. The room’s walls recede in gentle perspective, opening behind Christ into an ethereal halo of concentric arches and soft, prismatic bands—visual echoes of stained glass and spiritual radiance. This spatial choreography guides the viewer’s eye first to Christ’s face, then to the bread-breaking gesture, and finally into the luminous background that suffuses the scene with transcendent light.

Use of Color and Light

Color in Christ in Emmaus functions as theological language. Malczewski envelops Christ in vestments textured in warm ivory and gray-green, their subtle tonality distinguishing him from the richer hues around. The red of the disciples’ cloak and the blue of the tablecloth create complementary contrasts that heighten visual vibrancy. Yet it is the background’s iridescent bands—soft greens, pinks, lilacs, and sky blues—that impart the work’s mystical charge. These pastel arcs radiate from behind Christ’s head, functioning as a modern reinterpretation of the medieval halo or mandorla. Light itself becomes a character: it spills across hands and faces, pools in the bread’s crevices, and refracts through the unseen windows. Malczewski thus transforms the act of breaking bread into a cosmic event in which material substance becomes luminous sign.

Depiction of Christ and the Disciples

Malczewski presents Christ neither as ethereally aloof nor crudely human but as the perfect intersection of both. His countenance bears traces of sorrow and compassion—eyes half-lidded in solemn welcome, lips parted in mid-blessing. The hair and beard frame a face marked by the weight of passion yet tempered by gentleness. To Christ’s right, a disciple leans forward, expression caught between reverential awe and dawning comprehension. His hand reaches hesitantly toward the bread, as though preparing to partake in a sacrament. To the left, the other disciple kneels or sits, his posture more withdrawn, embodying the tension between doubt and faith. Malczewski invests each figure with individual psychology while uniting them in a single ritual act, underscoring Emmaus as a communal, not solitary, encounter.

Gesture, Expression, and Emotional Tone

Gesture plays a pivotal role in Malczewski’s narrative strategy. Christ’s bread-breaking motion is a precise ritual gesture—fingers splayed, wrist gently flexed—yet it carries electric emotional resonance. The disciples’ gestures mirror the act of receiving: one extends fingertips as though to catch crumbs of revelation; the other clasps his hands around a carved staff or fixed support, as if steadying himself against the surge of spiritual insight. The interplay of gazes and gestures creates a palpable tension that resolves only when the viewer’s eye ascends to the radiant background. Malczewski thus choreographs an emotional arc from human uncertainty to illuminated faith, tracing the disciples’ inner journey in bodily form.

Decorative and Allegorical Elements

Beyond its narrative core, Christ in Emmaus incorporates symbolic motifs drawn from Malczewski’s personal lexicon. The concentric bands behind Christ evoke not only sacred architecture—archways of church naves—but also the cyclical rhythms of time and eternity. Subtle vegetal ornament on the wall and faint glimpses of landscape through unseen windows hint at creation’s participation in the Eucharistic moment. The table itself, rendered with crisp realism, anchors the vision in everyday reality: a humble wooden slab, plain pottery, and simple glassware contrast with the scene’s spiritual intensity. Through these juxtapositions, Malczewski suggests that divine revelation occurs precisely when the ordinary and the sacred intersect, that Transfiguration need not transcend material life but can infuse it with meaning.

Technical Considerations and Painting Technique

Executed in oil on canvas, Malczewski’s Christ in Emmaus reflects his mastery of both academic and Symbolist techniques. X-ray studies reveal a carefully planned underdrawing wherein major forms—Christ’s posture, the table’s edge, background arches—are mapped out before color is applied. The paint handling varies: impasto in the robes and tablecloth contrasts with thin, translucent glazes in the background. Malczewski blends wet-into-wet on the disciples’ faces, achieving lifelike flesh tones, while the background’s pastel arcs require layering and delicate feathering. His choice of pigments—lead-tin yellows, cadmium reds, cobalt blues, and mixed earth greens—ensures both vibrancy and tonal subtlety. The painting’s well-preserved surface and minimal craquelure testify to the artist’s technical acumen and subsequent conservation.

Provenance and Exhibition History

Shortly after its completion in 1909, Christ in Emmaus was exhibited at the Zachęta National Gallery in Warsaw as part of a major showing of Malczewski’s Symbolist works. It drew considerable attention for its fusion of spiritual drama and modern style. In subsequent decades, the painting changed hands between private Polish collectors, surviving both wartime upheavals and the Communist era’s ambivalent attitude toward religious art. In 1967 it entered the permanent collection of the National Museum in Kraków, where it remains a centerpiece of early 20th-century Polish painting. Its inclusion in major retrospectives—most notably in Warsaw (1991) and Kraków (2009)—has reaffirmed its status as one of Malczewski’s most profound religious canvases.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Debate

Critics at the time lauded Malczewski’s Christ in Emmaus for its emotional immediacy and painterly innovation. Some traditionalists decried its pastel background as insufficiently “sacred,” yet many recognized in the concentric halos a uniquely modern apotheosis of medieval typology. Twentieth-century scholars have variously interpreted the work through theological, psychoanalytic, and national-cultural lenses. The painting’s emphasis on hospitality has been read as a parallel to Polish struggles for independence—welcoming international currents while preserving national identity. Psychoanalytic critics highlight the disciples’ ambivalent gestures as embodiments of conscience and faith in flux. Today, the work is celebrated for its capacity to speak across disciplines—art history, theology, psychology, and cultural studies.

Thematic Resonance and Contemporary Relevance

More than a historical curiosity, Christ in Emmaus continues to resonate with modern viewers seeking encounters between the mundane and the transcendent. Its depiction of revelation through shared ritual holds renewed relevance in an era marked by fragmentation and longing for authentic community. The painting’s delicate balance of physical realism and symbolic abstraction invites contemporary audiences to consider how art can mediate experiences of grace, recognition, and spiritual awakening. In a world often polarized between secular skepticism and religious literalism, Malczewski’s canvas offers a third path—one that honors tradition while embracing the artistic innovations that allow ancient mysteries to speak freshly to each generation.