Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

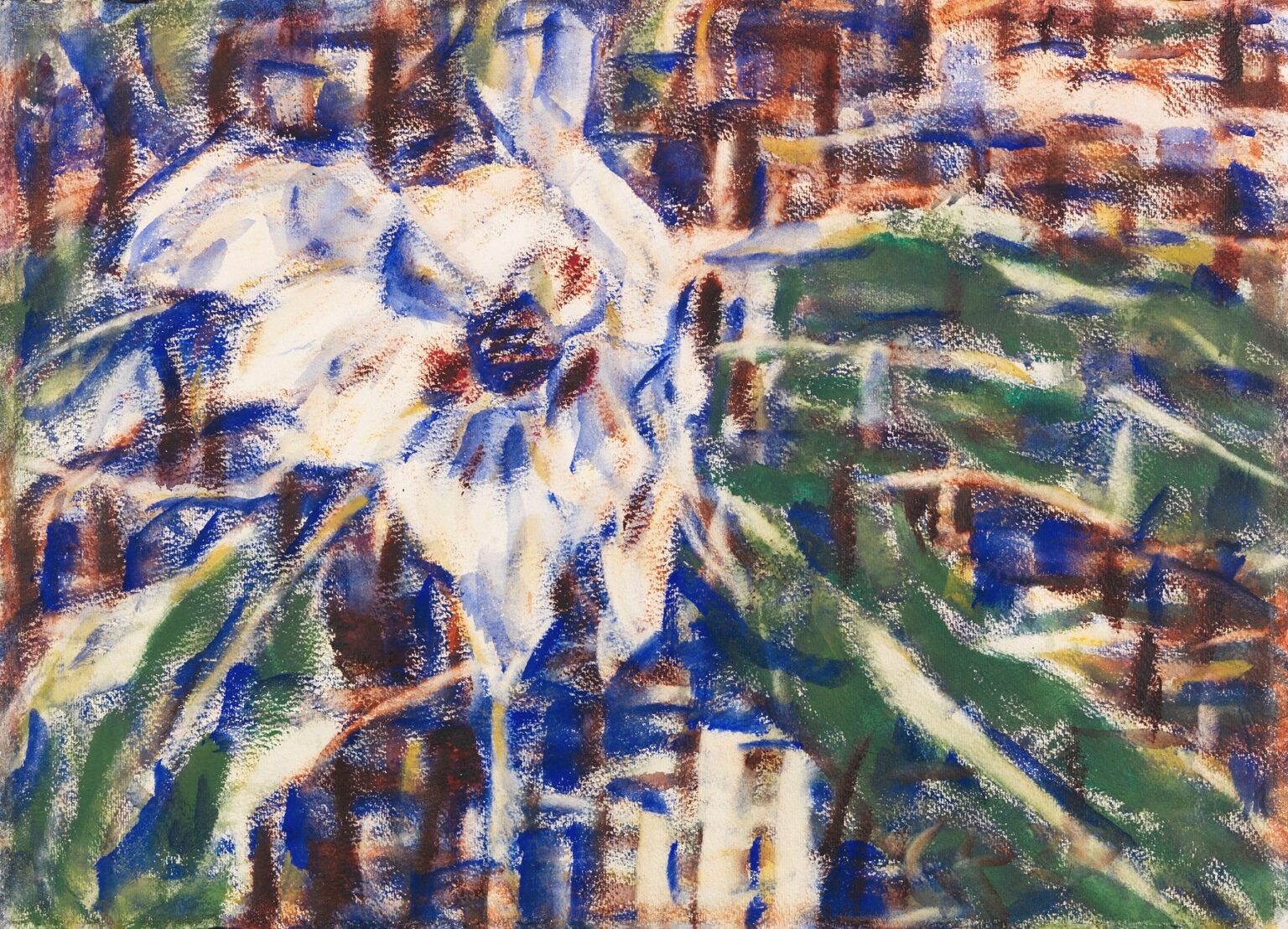

Christian Rohlfs’s Blue Magnolia (1929) stands as a breathtaking synthesis of natural observation and Expressionist innovation. In this late work, the magnolia blossom—usually rendered in soft whites or pinks—is reborn through Rohlfs’s daring use of blues, greens, and warm accents. Far from a mere botanical study, the painting transforms the flower into a dynamic interplay of color, light, and gesture. Rohlfs invites viewers to experience the magnolia not only as a visual delight but as an emotional and spiritual revelation. This analysis explores the work’s historical context, the artist’s late-career transformation, and the formal strategies—composition, palette, brushwork, medium—that make Blue Magnolia a seminal expression of twentieth-century modernism.

Historical Context

By 1929, Germany stood at the threshold of both artistic flourishing and political turmoil. The Weimar Republic’s cultural scene had produced ground-breaking achievements in cinema, architecture, and the visual arts, even as economic instability and social discord simmered. Expressionism, which had peaked before and during World War I, had evolved into a more introspective mode by the late 1920s. Artists sought to balance anguish with affirmation, abstraction with figuration, and personal vision with collective experience. Rohlfs, then eighty years old, navigated these currents with singular independence. While younger painters experimented with Constructivism or New Objectivity, he remained committed to the expressive potential of color and gesture, using the magnolia blossom as a means to distill beauty amid uncertainty.

Christian Rohlfs in the Late 1920s

Christian Rohlfs’s artistic evolution spanned over seven decades. After academic training in Düsseldorf and a phase of Realist landscapes, an illness in middle age propelled him toward more experimental media: watercolor, pastel, and tempera on paper. By the 1910s, he embraced the bold colors and distorted forms of German Expressionism, melding influences from French Impressionism with his own German heritage. The 1920s found Rohlfs in Soest, where he produced his most innovative work. Though he never aligned himself formally with any group, his late output—floral still lifes, nudes, and abstractions—reveals a mature artist who fused meticulous observation with unrestrained pictorial freedom. Blue Magnolia exemplifies this late style: a distilled vision that marries botanical form with the raw energy of paint.

The Subject: Magnolia in Bloom

Magnolia blossoms have long captivated painters with their sculptural forms and luminous petals. Typically associated with purity, renewal, and the fleeting nature of beauty, the magnolia here becomes a vehicle for Rohlfs’s expressive ambitions. The central bloom in Blue Magnolia fans open like a ghostly star, its tips brushing against a rhythmic background of vertical and horizontal strokes. Surrounding buds and foliage are suggested through fleeting gestures rather than precise delineation. Rohlfs thus honors the flower’s natural elegance while liberating it from strict representation. The magnolia transcends its botanical identity, emerging as a symbol of artistic transformation—white petals suffused with the painter’s inner life.

Composition and Spatial Structure

Rohlfs arranges Blue Magnolia within a horizontal format that underscores the blossom’s expansive form. The main flower occupies the left-central ground, its wide petals balanced by angular stems and foliage extending toward the right. Behind this focal area, a grid-like pattern of intersecting lines suggests a trellis, window, or abstracted environment. This lattice of strokes recedes and advances through varied brush pressure, preventing any rigid spatial hierarchy. Open areas of unpainted paper serve as breathing room, accentuating the vibrancy of painted passages. The composition’s blend of stable lattice and organic bloom creates a tension—echoing the interplay between structure and spontaneity that defines Rohlfs’s late work.

The Expressive Palette of Blue and Beyond

Color is the emotional engine of Blue Magnolia. Rohlfs substitutes magnolia’s usual ivory tones with a spectrum of blues—from deep ultramarine to soft cerulean—infusing the petals with a crystalline luminosity. Warm highlights of yellow ochre and burnt sienna peek through the blue, suggesting the sun’s warmth and the flower’s life force. Greens of the foliage vary from emerald to moss, punctuated by rust accents that recall autumnal decay, hinting at the blossom’s ephemerality. The background grid employs muted crimson and earthy browns, establishing complementary contrast with the cooler petals. This bold chromatic strategy elevates the magnolia from a passive subject to an active protagonist, radiating energy through the picture plane.

Brushwork and Surface Gesture

A master of varied mark-making, Rohlfs’s brushwork in Blue Magnolia is both assured and exploratory. The petals are modeled through wet-into-wet washes—soft, layered strokes that blend seamlessly—while the background grid is incised with dry, almost chalky passes. Some lines are heavily loaded, leaving thick pigment trails; others are merely wisps, where the paper’s warm tone shines through. The painting’s surface undulates with ridges of impasto alongside transparent glaze, creating a tactile topography that invites close inspection. Each stroke registers Rohlfs’s bodily engagement: the twist of the wrist, the press of the brush, the lift of pigment. The overall effect is a living canvas that breathes with the rhythms of creation.

Medium and Technical Approach

Blue Magnolia was most likely executed in tempera and pastel on heavy paper, a combination favored by Rohlfs for its immediacy and chromatic purity. Tempera’s egg-based binder yields swift drying and a matte finish, preserving the brightness of blues and yellows. Pastel or charcoal accents allow for crisp outlines and gestural contrasts. The paper’s tooth captures pigment granules unevenly, contributing to the painting’s tactile appeal. Rohlfs often layered media—applying a tempera wash, then defining forms with pastel, then reworking with tempera—resulting in a palimpsest of marks that reveal both process and polish. This mixed-media approach exemplifies his late-career search for synthesis between traditional technique and modern expressiveness.

Abstraction and Expressionist Language

While Blue Magnolia retains a recognizable subject, it flirts heavily with abstraction. The lattice in the background dissolves into a pattern of color patches and linear rhythms that verge on nonrepresentational. Petals themselves are flattened into planar shapes, sometimes merging with the background’s grid. This semi-abstract strategy echoes Expressionist aims: to convey inner experience over external verisimilitude. Rohlfs does not merely observe a magnolia; he inhabits its essence, mapping emotional states onto form and color. By dissolving clear boundaries between figure and ground, the work becomes an all-over field of sensation—anticipating later developments in abstraction and color-field painting.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance

Beyond its visual allure, Blue Magnolia brims with symbolic undertones. The blossom’s arresting blue suggests transcendence, urging viewers beyond earthly associations toward contemplative realms. The grid behind might evoke protective structure—trellis or lattice—that supports fragile life, symbolizing the interplay of freedom and constraint. Fleeting ripples of rust and green hint at seasons’ cycles, reminding us of nature’s impermanence. In 1929, as modern life trembled between innovation and instability, Rohlfs’s magnolia offered a vision of beauty that endures amid flux. The painting thus becomes a meditation on renewal, resilience, and art’s capacity to transmute fleeting moments into lasting revelation.

Comparison to Contemporary Works

Rohlfs’s Blue Magnolia can be compared to floral explorations by Emil Nolde and Carl Schmitz-Scholl, yet it distinguishes itself through its narrowed focus on abstraction and surface rhythm. While Nolde’s flowers blaze with Fauvist fervor, Rohlfs’s petals shimmer with a crystalline restraint. Compared to earlier Rohlfs still lifes—where forms remain more solid—the 1929 magnolia dissolves into pattern, aligning with interwar experiments in Cubism and Constructivism. Unlike the colder geometry of those movements, however, his lattice retains organic warmth, reflecting a uniquely German Expressionist sensibility. Blue Magnolia thus occupies a nexus between Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, and emerging abstraction, marking Rohlfs as both heir to and innovator of modernist painting.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its first display, Blue Magnolia intrigued critics and collectors for its daring palette and hybrid style. While not as commercially successful as some of Rohlfs’s earlier florals, it earned respect in avant-garde circles for its formal ingenuity. During the Nazi era, Expressionist works were often suppressed, but Rohlfs’s flower studies largely survived private and museum collections due to their apolitical subject matter. Post-World War II retrospectives rekindled interest in his late work, situating Blue Magnolia as a precursor to mid-century abstraction and color-field painting. Today, the piece is celebrated for its forward-looking synthesis of natural motif and abstract language, influencing contemporary painters exploring the porous boundary between representation and non-representation.

Conservation and Provenance

Blue Magnolia has been preserved with careful attention to its mixed‐media support. UV-filtering glazing and climate‐controlled display have minimized fading of delicate blues and yellows. High‐resolution imaging and pigment analysis confirm the presence of natural ultramarine, cadmium yellow, and iron‐oxide reds typical of Rohlfs’s palette. Provenance records trace the painting from Rohlfs’s studio in Soest to a private collector in Berlin, followed by donation to a regional museum in the 1950s. Minor retouching in the background grid addressed surface abrasions, but the work’s overall integrity remains remarkable. Conservation efforts continue to honor Rohlfs’s original layering and gestural vitality.

Conclusion

Christian Rohlfs’s Blue Magnolia (1929) stands as a luminous testament to the artist’s late‐career mastery of form, color, and expression. By rendering a familiar blossom in unexpected blues and embedding it within a dynamic lattice of brushstrokes, Rohlfs transcends mere depiction to evoke emotion, memory, and spiritual contemplation. The painting’s synthesis of observation and abstraction, its fusion of media, and its rhythmic composition place it at the forefront of interwar modernism. A century on, Blue Magnolia continues to captivate viewers with its blend of floral beauty and painterly innovation—an enduring anthem to art’s power to transform the ephemeral into the eternal.