Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

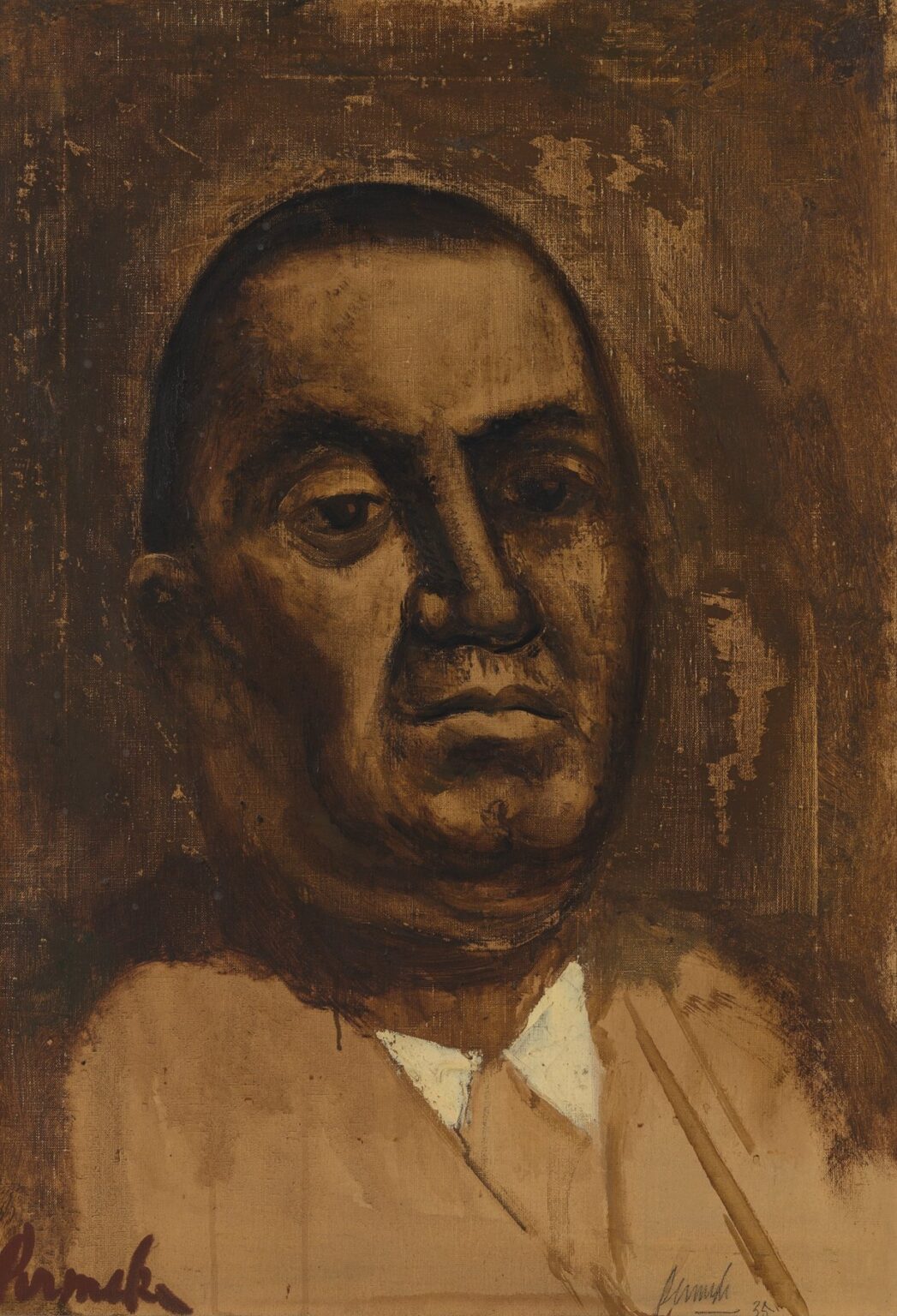

Constant Permeke’s “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” (1935) is a masterful testament to the artist’s shift from his early Expressionist celebrations of rural labor toward a quieter, more introspective mode of portraiture. In this work, Permeke distills his deep empathy for human presence into the solemn gaze and sculptural features of Gustave Van Geluwe. Rendered in warm earth tones and underpinned by a deliberate compositional economy, the portrait invites viewers into a private encounter with the subject’s character. Over the course of this analysis, we will explore the mid-1930s Belgian milieu that shaped the painting, trace Permeke’s artistic evolution up to this point, and examine the formal, chromatic, and textural qualities that give the work its enduring power.

Historical Context

Europe in 1935 was defined by the uneasy aftermath of the Great War and the gathering storm clouds of economic depression and rising authoritarianism. Belgium—still recovering from World War I—grappled with widespread unemployment and social unrest, even as neighboring Germany solidified its dictatorship. In the arts, many creators turned toward abstraction or bitter social critique, reflecting disillusionment with tradition and upheaval. Permeke, however, pursued an alternative path. Rather than retreat into nihilism or abandon the human figure, he embraced portraiture as a means of reaffirming individual dignity amid collective uncertainty. The austerity of his color palette and the absence of decorative flourish in “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” mirror the era’s material and emotional constraints, while the sitter’s composed bearing hints at the resilience needed to face an unpredictable future.

Artist Biography and Evolution

Born in 1886 in Antwerp and raised on a coastal farm in Ostend, Constant Permeke’s early career was steeped in the elemental forces of sea and soil. His studies at the Antwerp Academy coincided with exposure to Fauvism and German Expressionism, yet he returned to Flanders intent on grounding his art in everyday life. By the 1920s, he had gained renown for monumental canvases depicting fishermen hauling nets and peasants working the fields, characterized by thick impasto, simplified forms, and a rich earth-rooted palette. As the economic and political climate darkened in the early 1930s, Permeke’s focus narrowed. Large communal scenes gave way to smaller, more intimate studies, and his palette grew more muted. “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” marks a culmination of this transition. Here, Permeke channels the vigor of his earlier Expressionism into a refined exploration of a single individual’s presence, experimenting with thinner paint layers and a controlled compositional clarity that would define his late work.

Formal Composition

The structural balance of “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” is at once disciplined and dynamic. The sitter’s head and shoulders fill the vertical space, anchored by the strong axis of his elongated neck and the gentle incline of his chin. This vertical thrust is counterpoised by the subtle tilt of the head to the viewer’s left, introducing just enough diagonal tension to animate the pose without unsettling its serenity. The pale triangle of the shirt collar and the suggestion of a jacket lapel provide the sole horizontal elements, drawing the eye back to the face. The background, rendered in broad, horizontal strokes of deep umber and sienna, remains deliberately nondescript, pressing the sitter forward and dissolving any sense of environment. In this compressed pictorial space, every glance returns to the subject’s solemn gaze and sculptural modeling, forging a compelling intimacy between viewer and sitter.

Color and Light

Permeke’s choice of warm, muted earth tones underscores both his Flemish heritage and the painting’s subdued emotional tenor. The background’s deep browns and russets evoke aged wood or weathered stone, while the figure’s flesh is modeled in delicate washes of ochre and light umber. Thin layers of translucent paint allow the raw canvas to show through in places, lending the skin a gentle luminescence. Highlights are applied sparingly—along the bridge of the nose, the ridge of the forehead, and the curve of the lower lip—suggesting an ambient light source rather than a dramatic spotlight. Shadows are built through successive glazing of darker pigment, deepening beneath the brows, in the hollows of the cheeks, and under the chin. The pale collar, almost white against the somber tones around it, anchors the composition and focuses attention on the sitter’s face, while the overall tonal harmony reinforces the portrait’s quiet gravity.

Brushwork and Texture

A key characteristic of Permeke’s mid-1930s approach is his tactile engagement with paint. The background is composed of sweeping, horizontal scumbles that reveal both the artist’s hand and the weave of the canvas. On the face, brushstrokes become more directional, following the planes of the brow, the curve of the cheek, and the slope of the jaw. In some areas—particularly around the temples and neck—Permeke employs scraping or lifting to expose underlayers, introducing a time-worn patina that heightens the work’s textural complexity. The shirt collar, drawn with a few confident, almost calligraphic gestures, contrasts with the painterly richness of the flesh tones and background. These variations in handling transform the portrait into an object of palpable materiality, reminding viewers that they are encountering paint as much as image.

Anatomical Realism and Expressive Nuance

Although Permeke retains accurate proportions, he allows himself expressive license to emphasize character. The sitter’s neck is slightly elongated, granting an air of poise and drawing the eye upward. The brow ridge is pronounced, casting a thoughtful shadow over the deep-set eyes that meet the viewer’s gaze with calm intensity. Subtle asymmetries—one eye set marginally higher than the other, lips that curve ever so slightly uneven—grant the portrait vitality and guard against static perfection. The jawline is modeled with soft transitions of light and dark, suggesting bone structure without rigid line work. These anatomical choices serve not only to capture Van Geluwe’s likeness but to convey an inner life: a man shaped by experience, exhibiting both firmness of purpose and the vulnerability inherent in human existence.

Psychological Insight

More than a mere likeness, “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” is a psychological study. The sitter’s direct gaze creates an almost confrontational intimacy, yet the deep shadows under his brows and the careful modeling of his features evoke reserve rather than bravado. The slight downturn at the corners of the mouth hints at contemplation or even unspoken concern. The viewer senses a tension between vulnerability and resilience, as if Van Geluwe stands at the threshold between past tribulation and future uncertainty. In 1935, with Europe teetering on the brink of new conflict, such an expression would have carried profound resonance. Permeke’s portrait thus becomes an act of empathy, offering recognition of the sitter’s inner state without exploiting it for sensational effect.

Relation to Flemish Tradition

Flemish painting has long prized the truthful depiction of individuals, from Renaissance masters like Jan van Eyck to 19th-century realists. Permeke’s “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” inherits this commitment to honest observation but infuses it with modernist sensibilities. Where earlier Flemish portraits favored polished surfaces and meticulous detail, Permeke celebrates the visible mark of the artist’s hand and the canvas’s raw texture. His earth-rooted palette and insistence on corporeal presence tie the work to his rural and maritime scenes, even as the subject is urban and introspective. This synthesis—of local tradition and international Expressionist influence—makes the portrait feel both timelessly Flemish and strikingly of its era.

Position in Permeke’s Oeuvre

Within Permeke’s prolific career, the portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe stands as a milestone. It reflects the artist’s journey from the communal vigor of his 1920s labor scenes to the introspective refinement of his late work. Earlier large-scale canvases celebrated the physicality of rural toil; by 1935, Permeke had turned his gaze inward, seeking to capture the elemental humanity of a single individual. The painting anticipates his later nude studies—where he would explore vulnerability and resilience through the body—by demonstrating how compositional restraint and textural richness can convey profound emotional truth. As such, the portrait occupies a unique bridge between two defining phases of Permeke’s artistic evolution.

Conservation and Legacy

Since its creation, “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” has been exhibited in major Belgian salons and acquired by prominent museums dedicated to twentieth-century Flemish art. Conservators note that Permeke’s layering of translucent washes over thicker passages has remained remarkably stable, though the scraped and lifted areas require gentle environmental control to prevent abrasion. In scholarly discourse, the painting is often cited as exemplary of the artist’s mature portraiture, highlighting his ability to balance expressive brushwork with formal clarity. Its continued presence in retrospectives and publications cements its reputation as a pivotal work that illuminates both Permeke’s mastery and the broader currents of interwar European art.

Conclusion

In “Portrait of Gustave Van Geluwe” (1935), Constant Permeke transcends mere representation to craft a compelling study of individuality and resilience. Through a harmonious interplay of earth-toned palette, sculptural modeling, and tactile brushwork, he renders Gustave Van Geluwe’s presence with both fidelity and expressive depth. The sitter’s solemn gaze and composed posture evoke the quiet dignity of a man confronting uncertain times, while the painting’s material richness invites viewers to appreciate the act of painting itself. Situated at the nexus of Flemish tradition and modernist innovation, this portrait endures as a masterful affirmation of human dignity in the face of history’s pressures.