Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

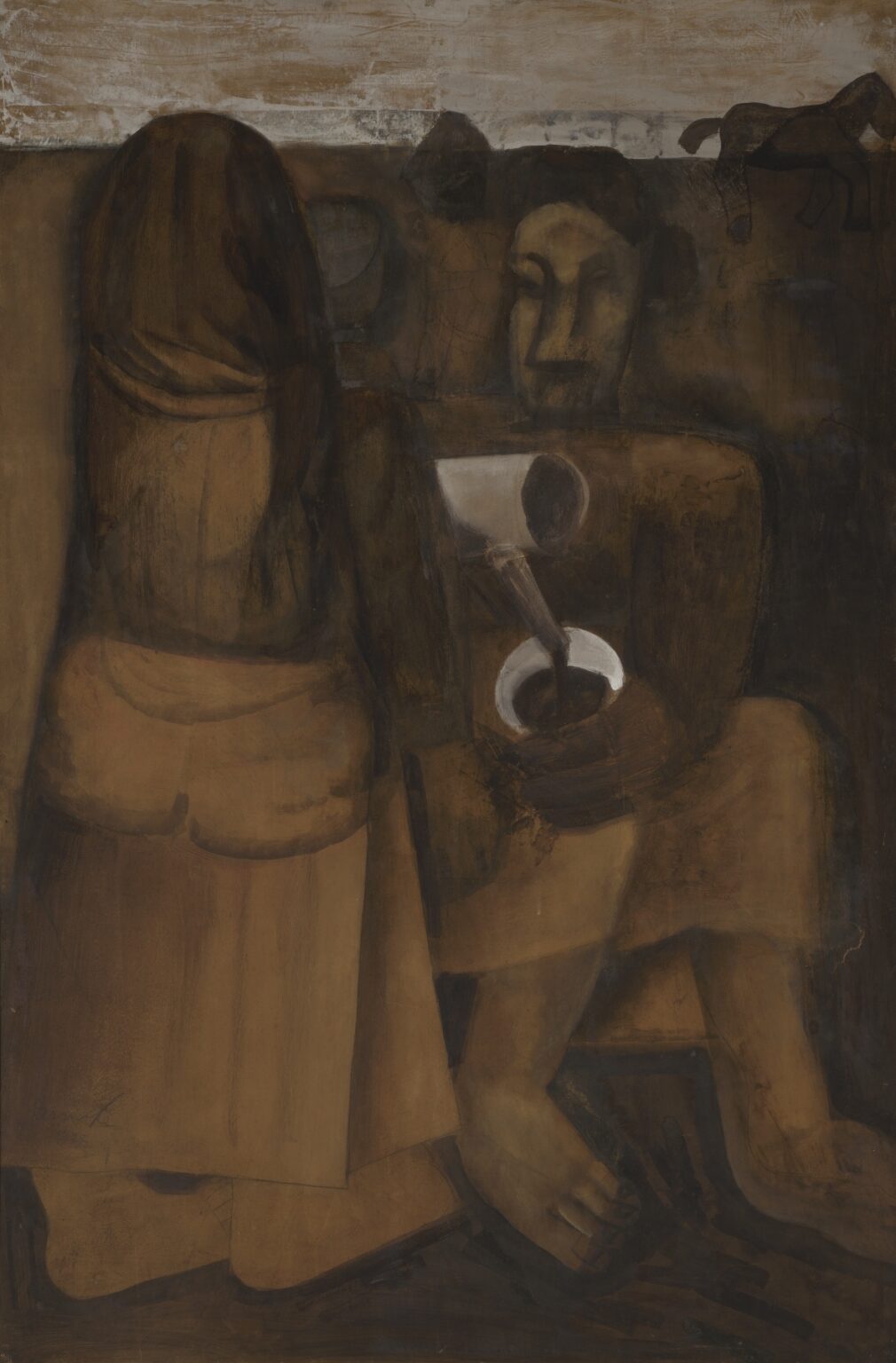

Constant Permeke’s Coffee Drinkers (1927) offers a striking window into the Belgian Expressionist’s mature period, when he distilled everyday rural scenes into powerful statements of human resilience and communal ritual. In this oil painting, Permeke captures two villagers—seated side by side—engaged in the simple yet intimate act of sharing coffee. Far from a cozy domestic scene, Coffee Drinkers pulsates with psychological intensity: massive, sculptural forms, an earth-toned palette, and emphatic brushwork convey the weight of everyday labor, the necessity of small comforts, and the quiet dignity of rural life in interwar Belgium. Through its evocative composition, nuanced handling of light and color, and layered symbolism, Coffee Drinkers transcends genre painting to become a meditation on human connection, endurance, and the sanctity of simple rituals.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1927, Constant Permeke (1886–1952) had firmly established himself as the leading figure of Flemish Expressionism. Born into a family of artists in Antwerp, he trained at the Royal Academy before traveling to the Belgian coast and West Flanders countryside. There, he befriended fishermen and farmers, immersing himself in their laborious routines. World War I interrupted his early promise—he served briefly in the Belgian army and witnessed wartime devastation—but the postwar years rekindled his commitment to rural subjects. In the 1920s, Permeke’s palette darkened, his forms grew more monumental, and his expressionist leanings deepened. Coffee Drinkers emerges from this mature phase, reflecting both the social hardships of the interwar period—economic uncertainty and the search for communal solidarity—and Permeke’s abiding interest in the intersection of work, ritual, and humanity.

Subject Matter and Symbolism

At first glance, Coffee Drinkers depicts two humble figures—a man and a woman—sharing a pot of coffee. Yet Permeke elevates this commonplace act into a symbolic ceremony. Coffee here stands for communal respite, a momentary reprieve from daily toil in fields or fisheries. The figures’ oversized hands and sturdy limbs emphasize physical labor, suggesting that coffee is not a luxury but a necessity that sustains work-worn bodies. Their downward gazes and slightly bowed heads evoke reverence: this is less a casual break than a shared ritual, verging on spiritual communion. The painting thus transforms a simple beverage into a metaphor for human solidarity and the search for warmth and connection amid hardship.

Compositional Structure and Spatial Dynamics

Permeke arranges the two figures in the central band of the canvas, their forms interlocking to create a unified compositional mass. The woman, on the left, is shown from behind in three-quarter view; her long hair and draped shawl frame the seated man at right, whose broad shoulders and bowed head form a counterbalance. Between them, a white coffee cup and pot become focal points, punctuating the warm browns and ochres with luminous contrast. The background, rendered in a patchwork of muted earth tones, recedes softly into ambiguity, allowing the figures to dominate the viewer’s attention. Horizontal lines—suggestive of a bench or hearth—anchor the scene, while the diagonal tilt of the woman’s body and the curve of the man’s arm introduce gentle dynamism. This interplay of stable horizontals and subtle diagonals grants the painting both solidity and expressive movement.

Palette and Color Harmony

In Coffee Drinkers, Permeke relies on a deliberately restrained palette of browns, ochres, siennas, and muted greens, evoking the earth, wood interiors, and work‐worn textiles of rural homes. The figures’ clothing—her shawl, his jacket—are painted in deeper umbers and umber mixed with black, establishing a warm yet somber mood. The coffee pot and cup, rendered in near-white highlights, stand out against this chromatic restraint, drawing the eye to the ritual at hand. Touches of pale pink on the faces and hands add subtle warmth, humanizing the massive forms without detracting from their monumentality. This chromatic economy reinforces both the painting’s emotional unity and its thematic emphasis on necessity over opulence.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Permeke’s brushwork in Coffee Drinkers is both bold and nuanced. He applies thick impasto to the figures’ coats and the coffee cup’s rim, creating relief-like surfaces that invite tactile engagement. In contrast, the man’s face and the woman’s hands receive more controlled strokes—short, crosshatched marks that model bone structure and skin texture. The background fields of color are laid in broader washes, their edges softened to prevent distraction. This variation—sculptural impasto for outer forms, finer modeling for flesh—demonstrates Permeke’s technical mastery and his commitment to expressing both physical weight and emotional nuance. Every stroke remains visible, contributing to the painting’s raw authenticity and immediacy.

Light, Atmosphere, and Mood

Rather than depicting a specific light source, Permeke employs an overall diffuse illumination that suggests the glow of a hearth or the filtered daylight of a farm kitchen. Highlights on the coffee cup, the man’s forehead, and the woman’s clasped hands are soft but distinct, guiding the viewer through the composition. Shadows, rendered in deep browns and muted greens, envelop the lower parts of the figures, enhancing their volumetric presence. This ambient lighting fosters an intimate atmosphere—part domestic interior, part sacred space—where ritual and daily life merge. The painting’s mood is contemplative: viewers sense quiet conversation, the rich aroma of brewing coffee, and the solace found in shared pauses.

Psychological Depth and Character

Permeke’s true gift lies in conveying psychological weight through simplified forms. The woman’s posture—turned slightly away, head inclined—suggests both reserve and attentiveness. The man’s drooping head and hidden face evoke weariness yet also absorption in the moment. Neither figure meets the viewer’s gaze directly; their focus remains on the cup and pot, reinforcing the coffee ceremony’s centrality. This inward orientation heightens the painting’s emotional resonance: viewers become privileged observers of a private ritual, invited to share in the protagonists’ unspoken bond. Permeke thus transforms rural realism into a study of human empathy.

Comparison with Permeke’s Other Works

Coffee Drinkers shares thematic DNA with Permeke’s earlier depictions of fishermen and farmers, where he portrayed labor’s physicality and camaraderie. In those works, figures often emerge from turbulent seas or muddy fields. Here, the action moves indoors, yet physicality remains palpable—evident in the figures’ solid forms and calloused hands. Compared to his 1925 Woman at Prayers, which channels spiritual devotion, Coffee Drinkers channels social devotion: the church replaced by the hearth, prayer by shared sustenance. Together, these works underscore Permeke’s holistic vision of rural life: a landscape of labor, ritual, and communal bonds.

Technique, Materials, and Conservation

Coffee Drinkers is executed in oil on canvas, a medium well-suited to Permeke’s layered approach. Examination of the painting reveals fine craquelure in thickly impastoed areas—particularly on the coat folds—and minor retouching along the coffee pot’s rim to preserve its luminous clarity. Conservation efforts have maintained the painting’s original tonal subtlety, ensuring the brown and ochre hues remain warm without darkening. Exhibited in major retrospectives of Permeke’s work, Coffee Drinkers continues to draw scholarly interest for its technical finesse and emotional power.

Cultural Significance and Social Commentary

Beyond its aesthetic merits, Coffee Drinkers offers insight into interwar Belgian society. Coffee—then a prized commodity—represented both modernity and comfort, a luxury that villagers saved for. By portraying this ritual, Permeke comments on the delicate balance between tradition (homebrew, communal sharing) and modern consumer culture (imported coffee beans). The painting thus engages with broader social currents: globalization’s early reach into rural life, the persistence of communal values, and the negotiation between old and new economic structures.

Legacy and Influence

Permeke’s Coffee Drinkers has inspired generations of artists exploring genre painting through expressive means. Its fusion of monumentality and intimacy offers a blueprint for depicting everyday rituals with psychological depth. Contemporary painters interested in food culture, domestic ritual, or rural heritage often cite Permeke’s work as a touchstone, recognizing its capacity to elevate the mundane into the universal. In Belgian art history, Coffee Drinkers remains a cornerstone, illustrating how Expressionist techniques can illuminate the human condition within familiar contexts.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Layers

The power of Coffee Drinkers lies in its layered complexity. On one level, viewers appreciate its compositional harmony, textural richness, and tonal subtlety. On another, they engage with its narrative: Who are these coffee drinkers? What have they endured? Why this moment of pause? Deeper still, the painting prompts reflection on communal rituals in audiences’ own lives: morning coffee, family gatherings, shared breaks at work. In this way, Permeke’s 1927 canvas transcends its specific setting to resonate with universal human experiences.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s Coffee Drinkers (1927) exemplifies the Flemish Expressionist’s ability to transform a simple domestic ritual into a profound meditation on community, labor, and emotional sustenance. Through sculptural composition, an earthy palette, dynamic brushwork, and empathetic characterization, Permeke captures the ritualistic gravity of sharing coffee—a moment of warmth and solidarity amid the demands of rural life. Over ninety years later, the painting continues to engage viewers with its emotional authenticity and technical brilliance, affirming its place as a masterpiece of 20th-century European art.