Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

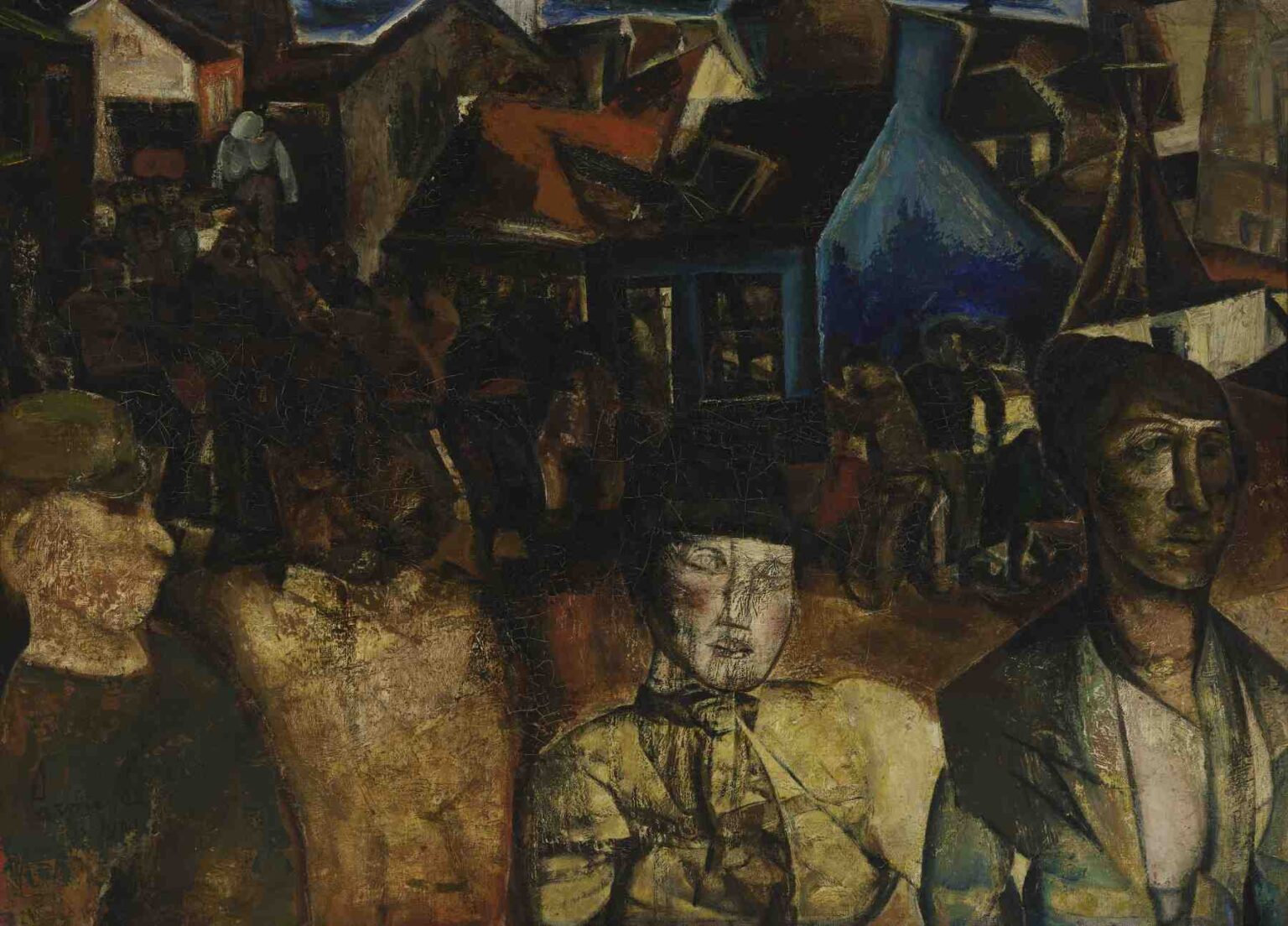

Constant Permeke’s Fair (1921) stands as a masterful synthesis of rural authenticity and Expressionist intensity. Painted in the interwar period, this canvas captures the lively yet somber spirit of a Belgian village fête—a fair where locals gather to trade, socialize, and momentarily escape the rigors of everyday labor. Far from a bucolic idyll, Permeke’s interpretation is layered with psychological depth: clustered figures stand before fair stalls and banners, their faces marked by solemn introspection rather than carefree revelry. Through a dynamic composition, a richly muted palette, and bold, textured brushwork, Fair transforms a communal event into a study of human resilience, social ritual, and the complex interplay between tradition and modernity.

Historical and Cultural Context

In the aftermath of World War I, Belgian society grappled with reconstruction, economic hardship, and cultural recalibration. Rural communities, whose men had fought at the front and whose women had maintained farms through deprivation, looked to local fairs for a sense of normalcy and communal bond. Fairs served as crucial social and economic gatherings—sites for selling livestock, purchasing household goods, and renewing social ties. Permeke, deeply rooted in West Flanders and attuned to rural life, turned his attention from fishermen and field laborers to the festive yet poignant spectacle of village fairs. Painted in 1921, Fair reflects this transitional moment: hope tempered by hardship, celebration shaded by collective memory of conflict.

Compositional Framework

Permeke structures Fair around two main registers: a dense foreground of standing figures and a busy midground of fair stalls and crowd activity. In the lower portion, roughly one third of the canvas, five figures stand almost shoulder to shoulder, their bodies rendered in sculptural mass. Their blank stares and stiff postures create tension, as if the ordinary joy of a fair has been paused for contemplation. Above them, tightly packed booths, banners, and indistinct shapes of wagons form a horizontal band. This midground is more loosely articulated, its forms overlapping in a flurry of angular brushstrokes that suggest movement and noise. The uppermost register, a narrow strip of sky, offers a momentary respite—a thin slice of pale blue that frames the turbulent scene below.

Focal Figures and Psychological Presence

Unlike conventional festival scenes, Permeke’s Fair does not invite viewers into the crowd but rather positions them before a group of detached onlookers. The central female figure, her head slightly tilted and hands clasped in her coat pockets, embodies quiet determination. To her left, a man with a flattened hat gazes unseeingly past the viewer; to her right, two more figures stand in empathetic solidarity, their forms partially obscured by painterly shadows. Each figure is given roughly equal visual weight, reinforcing the sense of collective experience rather than individual portraiture. Their solemn expressions—eyes downcast or unfocused—imbue the fair with a subdued, almost ritualistic atmosphere. In Permeke’s hands, the gathering becomes an act of communal endurance rather than simple amusement.

The Fairground as Social Microcosm

The midground’s fair stalls and signage are rendered with abbreviated lines and blocks of earthy color—ochres, siennas, burnt umbers—punctuated by flashes of cobalt blue and crimson. These shapes evoke vendors’ tents, wooden booths, and banners fluttering in a chilly breeze. Although details are minimal, the viewer can sense the fair’s commercial vitality: the trading of livestock, the sale of fabrics, the exchange of news. Yet the energy here is implied rather than explicit; the crowd behind the foreground figures is a blurred mass of activity. Permeke captures the fair as a social microcosm—an intersection of work and leisure, commerce and kinship—while maintaining the Expressionist focus on inner states over literal depiction.

Color Palette and Tonal Relationships

Permeke’s palette in Fair is tightly controlled, dominated by muted earth tones and punctuated by strategic color accents. The standing figures wear coats in shades of olive, sepia, and slate gray, their faces highlighted in pale cream. These low-key hues blend with the background stalls, creating visual unity. Against this, Permeke introduces small but brilliant accents: a triangular patch of cobalt on a booth roof, a red pennant at the canvas’s far left, and a pale banner arch spanning the middle register. These color notes guide the viewer’s gaze back and forth between figure and fête, linking the two realms thematically. The interplay of warm and cool tones—rusty browns against gray-blues—heightens the painting’s emotional tension, suggesting both the warmth of community and the chill of uncertainty.

Expressive Brushwork and Surface Texture

Visible, textured brushstrokes are central to Permeke’s expressive vocabulary. In the foreground, he applies thick impasto to sculpt the coats’ folds and the figures’ hats, giving them a monumental presence. Crosshatched strokes model their faces, carving out planes of light and shadow with urgency. By contrast, the midground fair stalls are painted more loosely: flat blocks of color overlaid with swift, directional dashes that suggest wood grain, canvas wrinkles, and bustling movement. The roughness of the surface—relief-like in areas—reinforces the work’s raw authenticity. Permeke’s brush never conceals itself; each stroke remains part of the narrative, conveying the tactile reality of cloth, wood, and weathered skin.

Light and Atmosphere

The light in Fair is diffuse, as if emerging through overcast skies. Permeke does not depict a distinct light source; instead, gentle illumination seems to envelope the scene, softening edges and unifying forms. Highlights on the figures—forehead, cheekbones, knuckles—are subtle, lacking the stark contrast of direct sunlight. This ambient lighting contributes to the mood of introspection: the fair takes place under a subdued sky, where spectacle is tempered by communal sobriety. The narrow strip of pale sky visible above the stalls hints at momentary clarity, a reminder of the world beyond the fête’s immediate concerns.

Symbolism of Gathering and Isolation

Permeke’s Fair embodies a paradox: a large gathering reduced to a handful of isolated individuals. While fairs serve to bring people together, the painting emphasizes personal interiority within a crowd. The foreground figures are physically close yet psychologically distant, each absorbed in thought. This dynamic suggests that communal rituals, even in festive settings, can coexist with individual solitude. The blurred crowd in the midground reinforces this tension: a mass where individual identities dissolve, contrasted with the sharply defined figures before it. Through this arrangement, Permeke comments on the human condition—the need for community alongside the privacy of inward reflection.

Comparison with Permeke’s Fishermen and Farmer Works

Permeke’s earlier canvases often depicted fishermen braving North Sea surf or farmers ploughing fields through mud. In those works, bodies dominate the scene, portrayed with muscular force. Fair shifts the focus from labor to social ritual, yet retains Permeke’s concern with physical presence and endurance. The festival-goers’ coats and hats echo the heavy protective gear of fisherfolk, emphasizing survival in harsh climates—social as well as natural. Both thematic strands—work and festivity—reflect Permeke’s holistic view of rural life: labor and leisure are intertwined, each demanding fortitude and community support.

The Fair as Cultural Ritual

Beyond its economic function, the fair in Permeke’s painting serves as a cultural ritual: a periodic reaffirmation of community ties, identity, and tradition. Stalls bearing local crafts and agricultural goods, banners marking familiar gathering spots, and the ritual procession of villagers through booths all speak to a cyclical rhythm that structures rural life. Permeke captures this ritualistic dimension, not through precise depiction but via composition and mood. The painting’s static solemnity hints at the serious importance of such gatherings—moments when community bonds are tested and renewed.

Psychological Underpinnings and Expressionist Aims

As an Expressionist, Permeke sought to convey psychological truth rather than optical realism. In Fair, this aim manifests in the painting’s emotional tenor: the solemn faces, muted light, and rugged textures create a sense of communal introspection. The work resonates with Expressionist concerns about modern alienation: even amidst social gatherings, individuals can experience isolation. Permeke transforms the fair from mere spectacle into a stage for exploring universal anxieties, hopes, and the search for meaning in shared rituals.

Technical Mastery and Conservation

Executed in oil on canvas, Fair demonstrates Permeke’s adept handling of both thick impasto and thin washes. The painting’s surface bears signs of fine craquelure in heavily textured areas, now stabilized through conservation. Retrospective varnishing has preserved the original color notes—particularly the vibrant cobalt and crimson accents—ensuring the scene’s emotional impact endures. Exhibited in major retrospectives of Belgian Expressionism, Fair continues to be recognized for its technical virtuosity and thematic depth.

Legacy and Influence on Rural Genre Painting

Permeke’s Fair has influenced subsequent generations of artists interested in the intersection of social ritual and individual psychology. Its fusion of genre painting traditions with Expressionist urgency offers a model for depicting community life with emotional authenticity. Contemporary painters exploring festival culture, street fairs, or communal gatherings often cite Permeke’s work as a touchstone, recognizing its capacity to convey layered meanings through figuration, color, and gesture.

The Viewer’s Experience and Interpretive Layers

Encountering Fair, viewers are drawn into multiple interpretive layers. At one level, the painting invites admiration for its compositional harmony and painterly technique. At another, it prompts reflection on community rituals and personal isolation. Still deeper, it resonates with historical realities of post-war Europe, where collective celebrations coexisted uneasily with the shadow of recent conflict. Permeke thus engages audiences not merely visually but intellectually and emotionally, fostering a rich dialogue between past and present.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s Fair (1921) stands as a landmark of Belgian Expressionism—a painting that transforms a familiar rural festival into a profound meditation on community, individuality, and the human spirit. Through his masterful composition, muted yet purposeful palette, bold brushwork, and empathetic portrayal of figures, Permeke captures the fair’s dual nature: a site of economic exchange and social ritual, joy tempered by introspection. More than a depiction of local custom, Fair speaks to universal themes of endurance amid hardship and the search for meaning in shared traditions. Over a century later, it continues to captivate viewers with its emotional depth and artistic brilliance.