Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

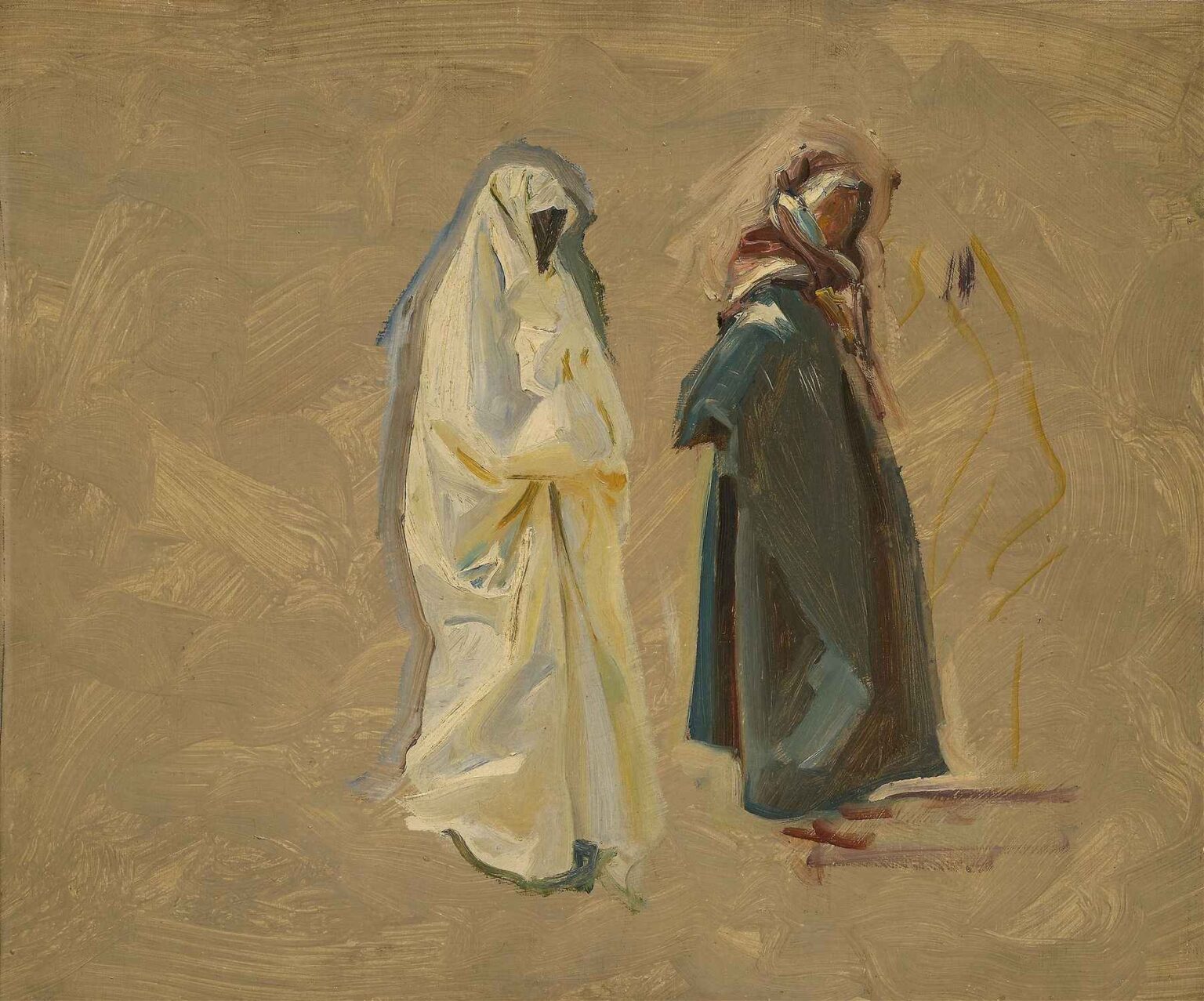

John Singer Sargent’s Study of Two Bedouins (1905) offers a captivating glimpse into the artist’s engagement with Orientalist subject matter and his mastery of alla prima oil sketching. Rather than a polished salon portrait, this work feels immediate and spontaneous—an on-the-spot study of two figures, wrapped in traditional robes, standing against a minimal, sand-toned ground. Through dynamic brushwork, a restrained palette, and a keen eye for form and gesture, Sargent transforms a simple sketch into a vibrant record of people, place, and culture. In this analysis, we will examine the painting’s historical context, compositional structure, use of light and color, brushwork, textiles and costume, cultural resonance, and its place within Sargent’s broader oeuvre.

Historical Context: Sargent’s Travels and Orientalism

At the turn of the 20th century, Sargent was at the height of his international reputation, admired for his society portraits in Paris, London, and New York. Yet beneath his formal commissions lay a restless curiosity about the wider world. Like many Western artists of his time, Sargent traveled extensively through Spain, Italy, North Africa, and the Middle East, seeking fresh subjects and chromatic inspiration. Orientalism—the Western fascination with Eastern cultures—provided artists a means to explore exotic motifs and dramatic light effects. In 1905, Sargent spent time in Morocco and Algeria, sketching local people in bustling markets and desert encampments. Study of Two Bedouins emerges from this period, capturing not an imagined fantasy but an encounter with individuals amid the shifting dunes of North Africa.

Subject and Setting: Two Bedouin Figures

The painting centers on two male figures, likely Bedouins—nomadic herders known for traversing desert regions. One wears a pale, voluminous mantle that envelops his form, while the other is draped in darker fabrics and a loosely wrapped head covering. Neither figure looks directly at the viewer; instead, Sargent depicts them in profile or three-quarter view, their faces partially obscured. This choice emphasizes observational detachment and respect, allowing the viewer to witness a candid moment rather than a staged tableau. The unadorned background suggests open space—perhaps a desert expanse—reinforcing the men’s connection to the land and the transient nature of their nomadic existence.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Sargent arranges the two Bedouins in a roughly vertical alignment, their bodies rising from the lower edge nearly to the top of the canvas. The left figure, clad in white, stands with more rigid posture, his mantle creating a sculptural silhouette. The right figure, in darker attire, leans slightly forward, adding a subtle diagonal tension. Between them, a narrow gap allows the warm ground tone to show through, separating their forms just enough to maintain individuality. The lack of horizon or architectural markers situates the figures in an abstract space, focusing attention on their attire and stance. This spatial economy mirrors Sargent’s intent: to capture the essence of the subjects rather than depict a full environment.

Use of Light and Color

The palette is deliberately limited. The ground is rendered in warm, sandy ochres, providing a neutral stage. Against this, Sargent sets the luminous white of the left figure’s mantle and the muted blues, greens, and browns of the right figure’s robes. Highlights—applied with quick, decisive strokes—catch the eye on the folds of cloth and the edges of head coverings. Shadows, built up through transparent glazes of warm umber and cool gray, ground the figures without overwhelming the sketch’s airy quality. The contrast between light and dark attire also enhances the figures’ individuality: one becomes a bright focal point, the other recedes into quieter contemplation. Overall, Sargent’s color choices evoke desert light—harsh yet warm, revealing form through subtle tonal shifts.

Brushwork and Technique

A defining feature of Study of Two Bedouins is its fluid, economical brushwork. Sargent works alla prima, applying paint wet-into-wet to capture instant impressions. The white mantle of the left figure is built from broad strokes of ivory, pale yellow, and cool white, merging seamlessly yet retaining visible brush edges that suggest fabric texture. The darker robes of the right figure employ shorter, staccato marks in deep greens and browns, conveying heavier textiles. Facial features and hands receive only the barest indications—just enough to register presence without distracting from the overall sketchlike quality. Sargent’s technique celebrates paint’s materiality: each stroke remains legible, infusing the work with vitality and spontaneity.

Textiles and Costume

Sargent demonstrates a profound sensitivity to textiles, rendering diverse fabrics through calibrated brushwork. The left figure’s mantle—perhaps a traditional Bedouin dishdasha or cloak—appears voluminous and soft, its layers suggested by gently overlapping strokes. The right figure’s garments, possibly comprised of a woolen outer robe and a woven headscarf, are articulated through plainer masses of color, punctuated by swift highlights along creased edges. The subtle interplay of line and tone conveys not only the physical qualities of the materials but also their cultural significance: these are garments shaped by desert life, protecting wearers from wind and sun. By focusing on drapery rather than detailed costume ornament, Sargent underscores authenticity over exotic spectacle.

Psychological and Cultural Resonance

Though Study of Two Bedouins is an observational sketch, it resonates with cultural depth. The lack of direct eye contact and the modest posture of both figures suggest humility and resilience—qualities essential to desert nomads. Sargent avoids oriental cliché (such as overly theatrical poses or overtly decorative patterns), instead presenting the men with dignity and restraint. The painting prompts viewers to consider the complexities of cultural encounter: the artist’s gaze is respectful yet curious, documenting without exoticizing. In doing so, Sargent elevates the work beyond ethnographic record to a portrait of human presence transcending cultural boundaries.

Influence of Arab Art and Islamic Tradition

While Sargent did not overtly imitate Islamic art’s ornamental aesthetics, his time in North Africa exposed him to the region’s architectural and decorative traditions. The broad, neutral background and emphasis on silhouette echo the effect of desert light on whitewashed walls and intricate stone reliefs. The interplay of shadow and light on draped fabric recalls the chiaroscuro found in Andalusian interior courtyards. Though Study of Two Bedouins remains resolutely Western in execution, its sensibility absorbs elements of Islamic art’s focus on form, pattern, and the interplay of clarity and mystery.

Comparison with Other Sargent Orientalist Works

Sargent’s later watercolors of Morocco and his oil Fumée d’Ambre Gris (1880) share with Study of Two Bedouins a fascination with atmospheric effects and immediate impressions. However, Repose and his Venetian scenes unfold in interior or urban contexts, whereas Study of Two Bedouins captures a more rugged, rural life. Compared to his detailed watercolors of Berber costumes, this sketch feels bolder and more abstract—an intentional reduction to essentials. In all these works, Sargent’s hallmark remains the same: an emphasis on light, energy, and the painter’s direct engagement with subject.

The Role of Sketch Studies in Sargent’s Practice

Sketch studies like Study of Two Bedouins were integral to Sargent’s creative process. He often used oil sketches to explore poses, lighting, and compositional ideas before tackling larger commissions. These studies were not mere preludes but standalone artworks valued for their spontaneity and freshness. Sargent recognized that the immediacy of sketching in situ—whether capturing a moment on a couch or in a desert encampment—imbued his work with an authenticity that studio paintings sometimes lacked. Collectors and museums later prized these sketches for the insight they provided into the artist’s method and his ability to seize the fleeting qualities of light and character.

Legacy and Influence

Study of Two Bedouins exemplifies how Sargent’s plein-air expeditions enriched Western art’s understanding of non-European cultures. His respectful approach influenced later portraitists and travel painters who sought authenticity over exotic fantasy. In the 20th century, artists like John Singer Sargent’s successor, Sir Alfred Munnings, continued the tradition of travel sketch studies, while contemporary painters cite Sargent’s brushwork and compositional boldness as models for capturing cultural encounter. The painting’s enduring appeal lies in its balance of documentary quality and painterly flair—a testament to Sargent’s belief that art thrives on direct observation and empathetic engagement.

Conclusion

John Singer Sargent’s Study of Two Bedouins (1905) stands as a vivid, respectful, and beautifully rendered glimpse into nomadic life. Through a masterful fusion of compositional clarity, nuanced color, and expressive brushwork, Sargent captures both the physical presence and cultural dignity of his subjects. The sketch exemplifies the artist’s skill in transforming on-the-spot observations into timeless works of art. Beyond its aesthetic virtues, Study of Two Bedouins invites us to reflect on the nature of cultural encounter—honoring difference through empathy and capturing fleeting moments of humanity amid the sweeping desert landscape.