Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: A Moment of Sensory Transcendence

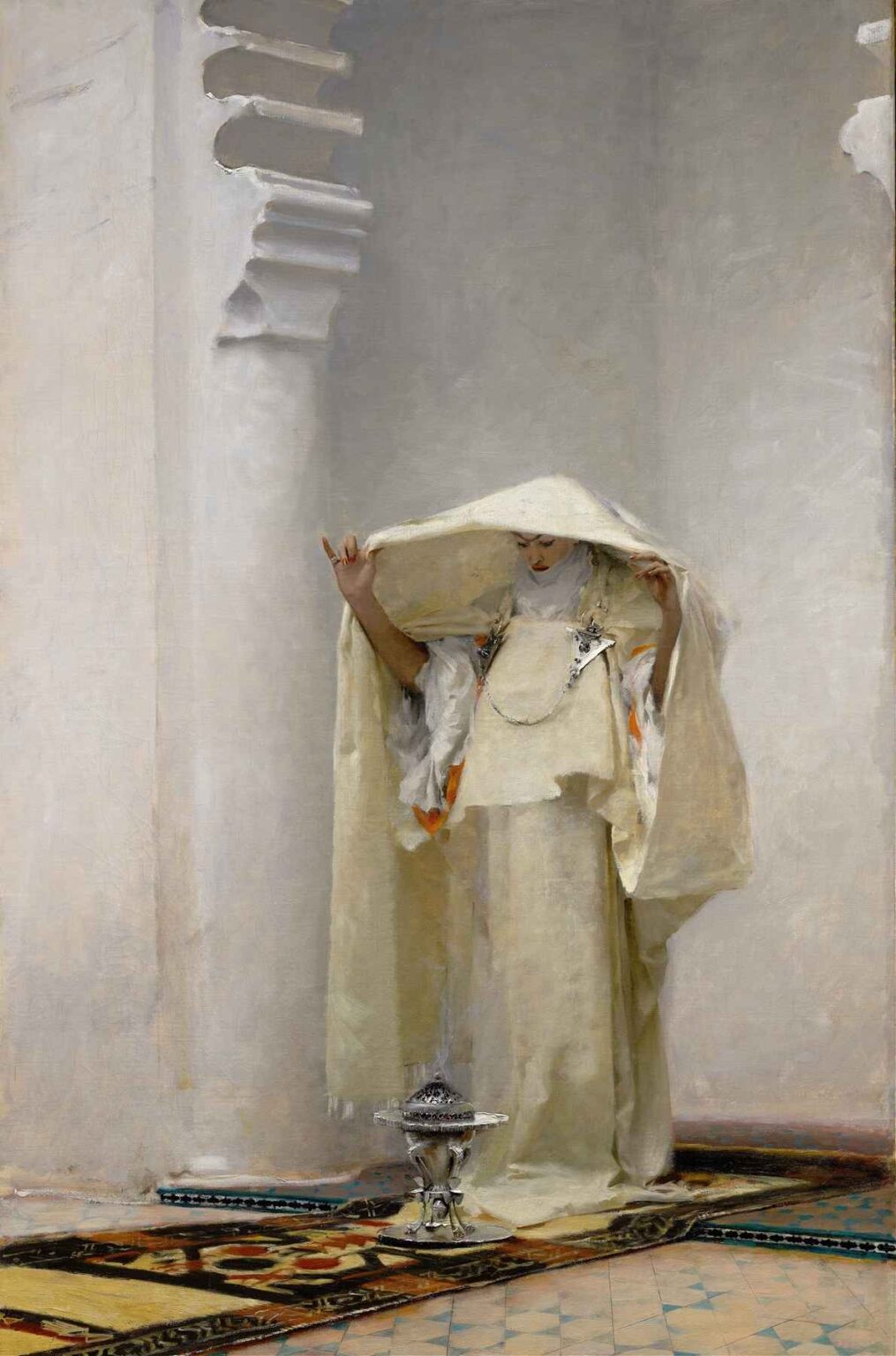

John Singer Sargent’s Smoke of Ambergris (1880) stands as a vivid testament to the artist’s affinity for evoking atmosphere and mood through his characteristic virtuosity with oil paint. Unlike his well-known society portraits or sunlit landscapes, this painting melds the exotic and the intimate, capturing a figure enshrouded in a cloud of fragrant smoke. The work offers viewers an immersive experience of texture, light, and scent—translated into visual form. In this analysis, we will explore how Sargent merges composition, palette, and cultural context to create a tableau that feels both timeless and deeply evocative of late-19th-century fascination with the Orient.

Historical Context: Western Fascination with the East

By 1880, Europe and North America were captivated by Orientalism—a cultural movement that romanticized and mythologized Middle Eastern and North African cultures. Explorers, writers, and artists flocked to cities such as Cairo, Damascus, and Algiers, seeking inspiration in unfamiliar customs and architectures. Ambergris, a rare aromatic substance produced by sperm whales, was prized in perfumery and incense ceremonies across the Islamic world. Sargent, who traveled extensively in the Mediterranean region, absorbed these influences into his work. Smoke of Ambergris emerges from this milieu of cross-cultural curiosity, reflecting both the era’s appetite for exotic subject matter and the artist’s skill in representing sensory phenomena.

The Sitter and Subject: Enshrouded in Fragrance

At the heart of the painting stands a veiled figure, her features obscured by a pale drapery that she raises with poised hands. She appears to perform a ritual, centering herself within the tending flames of an incense burner positioned at her feet. The ambergris smoke swirls around her, illuminated by the ambient light, creating a halo of aromatic vapor. Sargent does not specify her identity or provenance, leaving her as an emblematic presence rather than a particular individual. This choice enhances the universality of the scene: she embodies a timeless ritual of sensory immersion, invoking both mystery and reverence.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Sargent arranges Smoke of Ambergris within a near–symmetrical vertical format, allowing the viewer’s gaze to ascend from the incense burner at the bottom to the raised drapery framing the figure’s face. The painting’s lower third is anchored by the ornate burner and richly patterned carpet, while the upper two-thirds open into a luminous, architectural niche. Subtle receding lines in the carved arch hint at a marble alcove or mosque interior, though these details remain softly suggested. The central placement of the figure, combined with the vertical thrust of her garments, creates a sense of stillness and solemnity, as if one is witnessing a sacred moment of sensory devotion.

Use of Light and Color: Illuminating the Invisible

One of Sargent’s greatest achievements in this work lies in his depiction of translucent smoke. He uses delicate off-white and pale gray glazes to render the swirling vapor, letting the warm tonality of the background emerge through the thinner layers. Warm ochres and siennas in the walls and floor reflect the glow of an unseen light source, possibly a concealed lamp or shaft of sunlight. The figure’s pale robes echo this light, their folds catching highlights that reinforce the ethereal quality of the scene. Contrasting these luminosities are the deep shadows in the niche’s recesses, which amplify the sense that the smoke itself is a tangible, sculptural medium.

Costume and Textiles: Drapery as Ritual Vestment

The veiled figure’s garments—soft, off-white robes trimmed with subtle orange and gold accents—suggest ceremonial attire. The layers of fabric cascade in gentle waves, their edges rendered with swift, confident strokes that capture both volume and fluidity. The veil she lifts, painted with near-transparent brushwork, frames her hidden visage like a shroud of incense itself. Sargent’s tactile handling of fabric underscores the importance of textile in ritual: the act of donning robes, the sensation of cloth against skin, and the visual poetry of draping. The painter’s nuanced palette for the garments—balancing warm underpainting with cool highlights—renders drapery as both costume and extension of the surrounding smoke.

The Incense Burner as Symbol and Centerpiece

At the figure’s feet, a silver incense burner occupies a place of prominence. Rendered with sharp, reflective strokes, it stands in contrast to the soft textures of smoke and textiles. Its intricate latticework allows tendrils of smoke to escape, emphasizing the source of the aromatic mist that envelops the sitter. The burner anchors the composition, serving as a focal point for the viewer’s eye before leading upward along the stream of vapor. Symbolically, the burner connects earth and spirit—a vessel that transforms solid resin into sensory experience. Sargent’s attention to its metallic gleam and artisanal detail underscores its ceremonial significance and the artist’s respect for craft.

Brushwork and Technique: Suggestion Over Exhaustion

A defining feature of Sargent’s style is his ability to suggest form with minimal strokes, and Smoke of Ambergris exemplifies this economy. The smoke itself dissolves into the pale wall behind the figure, with feathered brushwork that leaves soft edges and wet-into-wet transitions. In contrast, the incense burner and the folds of heavier drapery receive more precise modeling, with thicker impasto and directional lines. This contrast between controlled detail and impressionistic freedom animates the canvas, allowing the eye to linger on areas of clarity before drifting into more atmospheric passages. Sargent’s technique invites viewers to participate in the painting’s making, filling in details with their own perception.

Architectural Setting and Atmosphere

Although the architectural elements are secondary, they play a vital role in situating the ritual. The carved arch framing the figure suggests Moorish or Andalusian design, hinting at Sargent’s exposure to Islamic architecture during his travels in Spain and North Africa. Vertical ridges on the wall recall scalloped arches seen in Alhambra and other palaces. Yet these references remain muted; Sargent avoids explicit geographic detail in favor of an impression of sacred space. The result is an environment that feels universal to any setting of fragrant devotion—whether a temple, palace, or private chamber.

Sensory and Psychological Impact

Smoke of Ambergris transcends visual representation to evoke the sensation of fragrance itself. The viewer can almost smell the sweet, animalic perfume of ambergris, inhaling the swirling mist that animates the scene. Sargent’s delicate color harmonies and atmospheric effects create a sensory synergy: sight becomes scent, paint becomes perfume. Psychologically, the painting invites contemplation—drawing viewers into a moment of meditation where the external world recedes and the ritual of scent becomes a gateway to introspection. The veiled figure’s downward gaze reinforces this inward focus, suggesting an intimate communion with the ineffable.

Orientalism and Cultural Dialogue

While the painting participates in Orientalist tradition by depicting an exotic ritual, Sargent approaches the subject with reverence rather than caricature. He refrains from sensationalizing the scene; instead, he treats the ambergris ceremony with the solemnity of a religious act. This restraint distinguishes Sargent from some contemporaries who indulged in lurid fantasies of the East. His nuanced palette, focus on sensory immersion, and respect for cultural artifacts point to a more empathetic engagement. Smoke of Ambergris thus becomes a bridge between Western viewers and non-Western practices, honoring the ritual’s aesthetic and spiritual potency.

Comparison with Sargent’s Other Orientalist Works

Sargent’s oeuvre includes several works inspired by his travels—watercolors of Moroccan souks, oils of Spanish dancers, and sketches of Middle Eastern architecture. Compared to more vivid tableaux like Moroccan Street Scene or The Street of the Tombs, Smoke of Ambergris is hushed and inward. It shares with Fumée d’Ambre Gris (its original French title) a focus on subtle atmospheric nuance rather than bustling activity. The painting’s emphasis on ritual and sensory experience sets it apart, reflecting Sargent’s evolving interest in capturing not only the visual exoticism of foreign lands but also the intangible qualities that define cultural practices.

Sargent’s Artistic Philosophy: Transcending Surface

Throughout his career, Sargent championed the idea that painting should convey the essence of a subject rather than slavishly reproduce every detail. In Smoke of Ambergris, this philosophy is manifest: the work communicates the vaporous quality of incense, the hush of ritual, and the weight of drapery through carefully calibrated paint handling. Sargent understood that paint could evoke emotion as powerfully as line. By allowing forms to dissolve into atmosphere, he invites viewers to move beyond surface appearances and engage with the painting’s deeper sensory and symbolic resonances.

Legacy and Influence: Sensory Abstraction

Smoke of Ambergris presages 20th-century explorations of abstraction and sensory immersion. Its prioritization of atmosphere over narrative and its use of paint to evoke scent and sound anticipate modern artists who sought to break from strict representationalism. Painters such as James McNeill Whistler and later abstractionists recognized Sargent’s achievements in atmospheric painting. Contemporary creators working with installation and olfactory art can trace a lineage to Sargent’s recognition of scent as an integral component of aesthetic experience.

Conclusion: The Alchemy of Paint and Perfume

John Singer Sargent’s Smoke of Ambergris remains a singular achievement in late-19th-century painting. Through a synthesis of refined technique and sensory imagination, Sargent transforms a fleeting ritual into an enduring visual poem. The painting’s careful composition, nuanced palette, and transparent brushwork fuse sight and scent, inviting viewers into a realm where the boundaries between art and ritual dissolve. More than a depiction of exotic ceremony, Smoke of Ambergris stands as a monument to the power of painting to evoke the invisible—perfume, prayer, and the ineffable beauty of transience.