Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

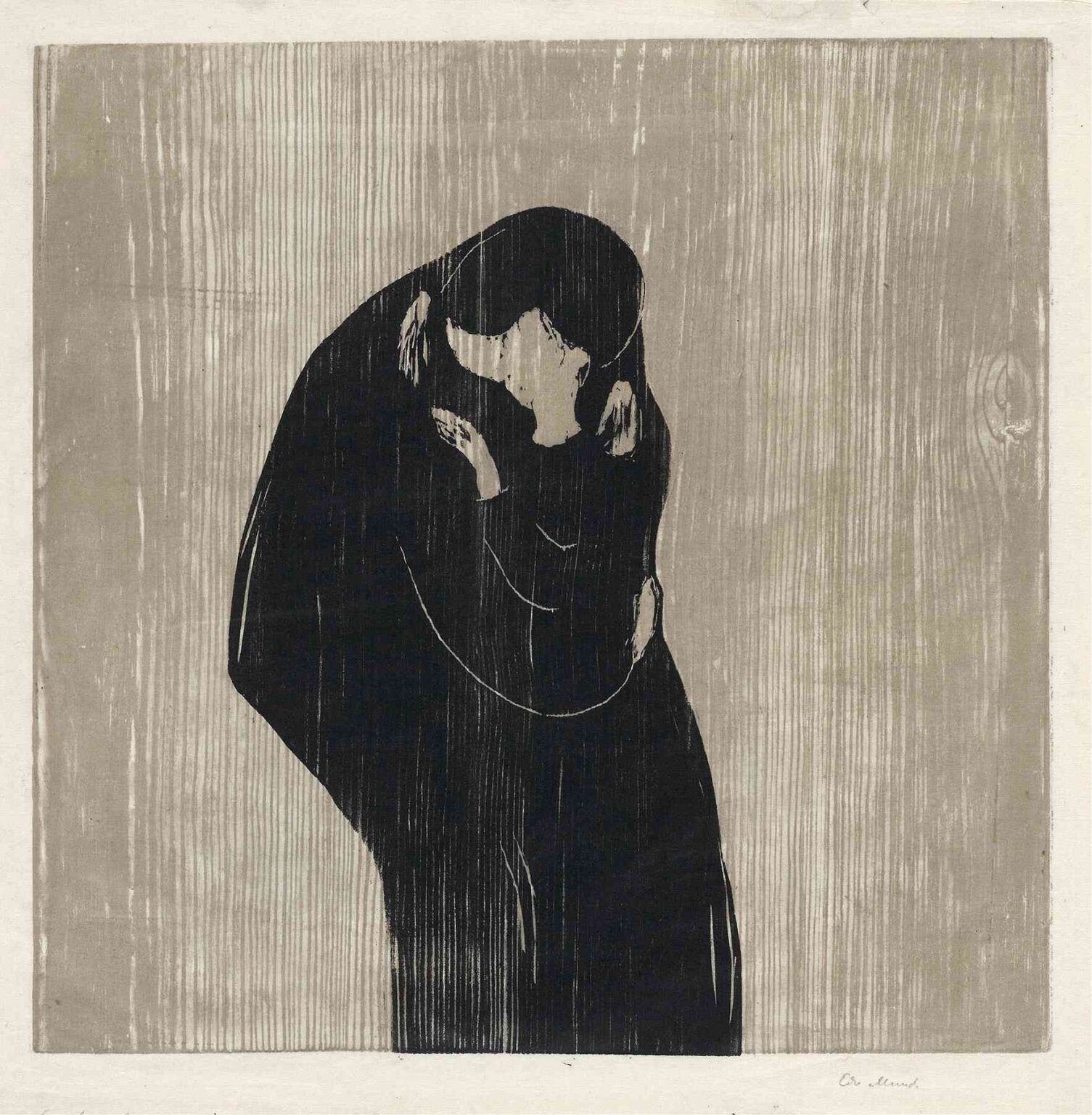

Edvard Munch’s The Kiss IV (1902) is one of the most intimate and psychologically charged of his many explorations of human relationships. Rendered as a color woodcut, the image depicts a pair of lovers locked in an embrace that simultaneously conveys passion, ambivalence, and existential unease. At first glance, the composition appears deceptively simple—a faceless couple wrapped in a dark cloak against an abstract background—yet its pared-down forms and stark contrasts reveal a complex interplay of desire, identity, and emotional tension. This analysis will examine how Munch transforms the universal theme of the kiss into a profound meditation on connection and alienation, using formal techniques and symbolic gestures that mark a pivotal moment in his artistic development.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1902, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had firmly established his reputation across Europe as a leading voice of Symbolism. His breakthrough painting The Scream (1893) and subsequent works such as The Madonna (1894–95) had drawn both acclaim and controversy with their raw emotional content. Munch’s life was punctuated by personal tragedy—his mother’s death when he was five, the loss of his sister Sophie in 1877, and ongoing health struggles—that fueled his fascination with themes of sickness, death, and psychological suffering. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, he spent extended periods in Berlin and Paris, absorbing avant-garde currents while refining his printmaking techniques. The Kiss IV emerges from this period of experimentation, reflecting Munch’s desire to distill emotional experience into elemental visual language and to disseminate his ideas through reproducible graphic media.

The Kiss Series and Evolution

Munch’s interest in depicting the kiss stretches back to his earliest works. He began with painted versions—cheerful and naturalistic—before shifting toward more introspective and stylized treatments. By the time of The Kiss IV, the motif had evolved from a symbol of romantic fulfillment into a more ambiguous emblem of emotional entanglement. Earlier woodcuts, such as The Kiss I (1894), retain hints of comfort and unity; in The Kiss IV, however, the lovers are subsumed by a shadowy garment, their faces rendered featureless and fused together. This progression mirrors Munch’s own shifting view of intimacy: once an affirmation of life, now an arena for exploring the fragility of selfhood and the tensions inherent in merging with another.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

The composition of The Kiss IV is built on stark contrasts of dark and light, figure and void. The lovers occupy the central vertical axis, their bodies concealed beneath a heavy cloak that approximates an abstract silhouette. The cloak’s sweeping curve creates a rhythmic counterpoint to the simple rectangular border of the woodcut. Behind them, a flat ground plane is bisected by a pale strip of uninked paper that suggests horizon or threshold. Above this line, vertical brushlike strokes of muted ochre and green evoke a distant landscape or interior wall. Munch’s elimination of detailed setting intensifies the focus on the act of embrace itself, while the empty background amplifies a sense of isolation—two figures in a vast, undefined space.

Color, Light, and Mood

In The Kiss IV, Munch employs a limited yet resonant palette: deep blacks dominate the cloaked figures, while soft ochres, pale greens, and faint pinks animate the surrounding field. The lovers’ faces—mere outlines of nose and chin—emerge in the pale paper, as if illuminated from within by an inner glow. This chiaroscuro effect underscores the intimacy of the moment even as it casts the scene in an eerie light. The dark cloak absorbs most of the ink, creating a silhouette that feels at once protective and suffocating. The surrounding hues shift subtly across the surface, hinting at atmospheric changes—perhaps the waning light of day or the inner turbulence of the lovers. Overall, the mood is one of quiet intensity, poised between solace and unease.

Technique and Medium

As a color woodcut, The Kiss IV showcases Munch’s mastery of relief printmaking. He carved multiple blocks—each corresponding to a different color—requiring exact registration to align the final image. Departing from the crisp precision of traditional Japanese woodcuts, Munch allowed the grain of the wood to show through in areas of light application, creating a tactile, organic texture. His inking method varied from dense imprints to delicate, uneven layers, imparting a painterly quality to the print. The lovers’ cloak, for instance, bears the rich, velvety black of heavy inking, while the background colors are applied more sparingly, allowing the wood grain’s natural tonality to animate the surface. This hybrid approach blurs the line between print and painting, underscoring Munch’s desire to capture fleeting emotional states.

Symbolism and Thematic Interpretation

The act of kissing has long symbolized union, passion, and affirmation of life. In Munch’s hands, however, it becomes a site of psychological ambiguity. The lovers’ featureless faces meld into a single mass, erasing individual identity and suggesting a potential loss of self within the relationship. The enveloping cloak functions as both shelter and prison: it conceals the lovers from external view, yet its weight and darkness hint at the oppressive aspects of intimacy. The horizon line behind them may symbolize a threshold—between self and other, inside and outside, life and death. Some interpretations view The Kiss IV as an allegory for death: the embrace resembles a mortuary shroud, and the faint, otherworldly glow of the faces suggests spirits glimpsed in twilight. Others read it as a critique of romantic idealization, exposing the subtle anxieties that accompany physical and emotional closeness.

Psychological Dimensions

Munch’s enduring fascination with the human psyche informs every facet of The Kiss IV. By abstracting the lovers’ features, he universalizes their experience—viewers can project their own feelings of desire, fear, or resignation onto the figures. The imbalance between the enveloping cloak and the fragile glow of the faces creates a palpable tension: the longing to merge with another versus the instinct to maintain personal boundaries. This dynamic mirrors psychoanalytic theories of the turn of the century, particularly Freud’s notions of eros and thanatos (life and death drives). According to Munch’s own writings, he saw love as inseparable from longing and loss; The Kiss IV makes this dialectic visible, offering a visual metaphor for the interplay of attraction and anxiety.

Relation to Munch’s Broader Oeuvre

The Kiss IV occupies a key position in Munch’s exploration of relational themes alongside series such as Frieze of Life (1893–1918). Earlier paintings in the sequence—Love and Pain (1895), Ashes (1894), Madonna (1894–95)—all address the paradoxes of love, death, and creativity. Yet the woodcut medium allows Munch to distill these concerns into elemental contrasts and gestures. Compared to his color paintings, the prints reveal a more restrained formal language, one that emphasizes silhouette and tonal interplay over elaborate composition. Munch’s influence on German Expressionists—Kirchner, Heckel, and Nolde—can be traced directly to works like The Kiss IV, where heightened emotion is conveyed through minimal means. The print also foreshadows later modernist experiments in abstraction, where the figure becomes a cipher for universal psychological states.

Reception and Legacy

At its initial publication, The Kiss IV drew admiration from critics for its technical innovation in color woodcut and its evocative emotional resonance. Avant-garde journals reproduced select impressions, and collectors sought out the hand-colored versions for their painterly subtleties. Over the past century, the print has been featured prominently in retrospectives of Munch’s graphic work, where scholars highlight its pivotal role in expanding the expressive potential of printmaking. Its imagery has permeated popular culture—from stage design in modern theater to cinematic motifs of lovers escaping into shadow. Today, The Kiss IV is recognized not only as a masterful example of early 20th-century printmaking but also as a timeless meditation on the complexities of human connection.

Conservation and Provenance

Original impressions of The Kiss IV are held in leading collections, including the Munch Museum (Oslo), the British Museum (London), and the Museum of Modern Art (New York). Conservationists emphasize the need to preserve the delicate layers of colored ink, especially the subtle ochre and green overlays that can fade under strong light. Technical studies—using microscopy and spectral imaging—have documented Munch’s inking variations, revealing slight differences between impressions that underscore his hands-on involvement in each print. Provenance records trace early editions through private collectors in Scandinavia and Germany before acquisition by major public institutions in the early 20th century. Scholars often compare multiple impressions side by side to illustrate Munch’s evolving inking techniques and color choices.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond its art-historical impact, The Kiss IV resonates with universal experiences of desire, union, and the tensions they engender. In literature, the image has been invoked to illustrate themes of consuming passion and existential dread. Psychologists reference it when discussing the interplay of intimacy and individuation. Contemporary photographers and filmmakers echo its formal economy, using shadow and silhouette to suggest emotional complexity. In design, the motif of the embracing cloak has inspired motifs in fashion and graphic identity projects that explore themes of protection and vulnerability. The enduring power of The Kiss IV lies in its ability to speak across disciplines and eras, reminding viewers that even the most universal human gestures can harbor hidden depths.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch’s The Kiss IV stands as a testament to the artist’s singular vision: the capacity to render the most intimate human act with a spare, almost abstract, formal language that lays bare its psychological underpinnings. Through the color woodcut medium, Munch harnesses contrasts of light and dark, silhouette and glow, to evoke a moment of embrace that is at once comforting and fraught. As both a milestone in the evolution of printmaking and a profound inquiry into the nature of love, The Kiss IV endures as a work of enduring mystery and emotional power—an invitation to contemplate the fragile boundary between self and other that defines human connection.