Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

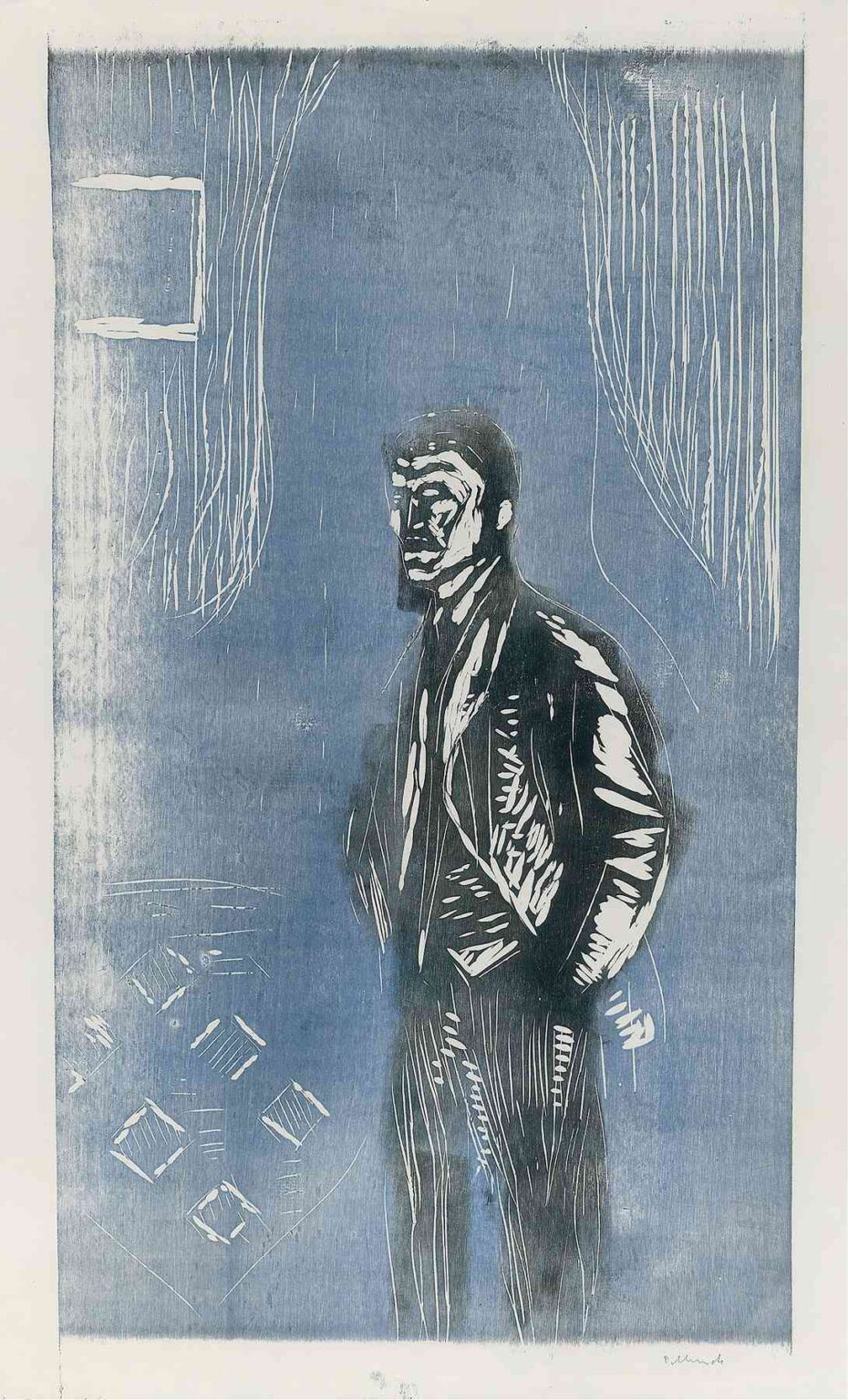

Edvard Munch’s Self-Portrait in Moonlight (c. 1902) is a striking exploration of identity, mood, and the interplay between artist and environment. Rendered as a color woodcut, this work presents the artist himself standing before a pale window, bathed in the chill glow of moonlight. Unlike Munch’s other nocturnal scenes featuring anonymous figures, here the artist turns the gaze inward, framing his own visage within a realm of shadow and reflection. Through a contemplative composition, restrained palette, and innovative printmaking technique, Munch transforms a self-portrait into a poetic meditation on solitude, creative self-awareness, and the liminal space between inner life and outer world.

Historical and Biographical Context

At the turn of the twentieth century, Munch was navigating personal and professional crossroads. Having established his reputation with emblematic works such as The Scream (1893) and Madonna (1894–95), he sought new means to express the intangible realms of emotion and psyche. His move to Berlin in 1896 had broadened his exposure to avant-garde circles and printmaking innovations. By 1902, Munch was increasingly drawn to graphic media—woodcut, lithography, and etching—to disseminate his ideas beyond the canvas. Self-Portrait in Moonlight emerges from this period of experimentation, reflecting his fascination with nocturnal light and the psychological resonance of liminal moments.

Artistic Background and Influences

Munch’s portrait draws upon multiple artistic traditions. His admiration for Japanese ukiyo-e is evident in the simplified forms and flat planes of color. At the same time, Symbolist concerns with mood and inner states shape the work’s thematic core. The tradition of the self-portrait as a means of self-examination—from Rembrandt to van Gogh—provides another layer of reference, yet Munch subverts convention by placing himself not in a brightly lit studio, but against the ambiguous backdrop of night. The result is a hybrid that melds printmaking’s graphic clarity with Symbolism’s evocation of emotion.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

In Self-Portrait in Moonlight, Munch positions himself slightly off-center, facing toward the right edge of the image. The edge of a window frame appears behind his head, its panes delineated by pale lines that suggest cool lunar light filtering inward. The figure’s shoulders and upper torso occupy the foreground, while behind him the wall dissolves into a vertical wash of muted blue. Munch’s use of vertical lines—from the hanging curtain to the drips of ink—creates a sense of downward motion, as if the moonlight is softly cascading over the scene. This interplay of figure and field generates an intimate yet spacious atmosphere: the artist exists both within the domestic interior and under the vast canopy of night.

Color, Light, and Atmosphere

Munch employs a limited palette dominated by soft blues, silvery whites, and deep blacks. The primary hue—a translucent cerulean—spreads across the background, invoking the cool hush of moonlit night. In contrast, the artist’s face and hands are rendered in pale white paper tones, creating a spectral luminosity that seems to emit from within. Black ink outlines his features and garments, anchoring the composition and providing weight. Subtle gradations—achieved by variable inking and wiping—allow the moonlight to shimmer across surfaces. The overall effect is one of quiet intensity: the scene feels still yet alive, suspended between wakefulness and dream.

Technique and Medium

As a color woodcut, Self-Portrait in Moonlight showcases Munch’s mastery of relief printing. He carved separate blocks for each color layer—a demanding process that required precise registration. The result is a layered image in which the blue background, white highlights, and black outlines interlock seamlessly. Munch treated the wood grain as a textural partner, allowing it to remain visible in areas of lighter ink, which adds an organic irregularity to the print surface. His approach marries painterly sensitivity—through nuanced washes of color—with the bold directness of printmaking, demonstrating how graphic media can convey subtle mood and form.

Symbolism and Thematic Interpretation

Moonlight in Munch’s work often symbolizes the unconscious, the realm of dreams, and emotional reflection. In this self-portrait, the moonlit window becomes a metaphorical threshold: the artist stands at the boundary between his interior world and the external cosmos. His gaze, directed slightly away from the viewer, suggests introspection rather than confrontation. The empty room behind him speaks of solitude and creative isolation. Yet the window’s glow also hints at inspiration drawn from the night sky. Thus the work embodies a dual theme: the tension between self-imposed seclusion and the yearning for illumination that drives the artist’s vision.

Psychological Dimensions

Munch understood art as an avenue for exploring the psyche. Here, the artist’s own image becomes a proxy for universal states of mind: the isolation of the creative process, the vulnerability of self-revelation, and the allure of solitude. The delineation between dark clothing and luminous skin echoes the dialectic of conscious and unconscious. The downward cascade of the background lines can be read as tears or the gentle pull of memory. By depicting himself in a moment of quiet reverie rather than dramatic anguish, Munch broadens his psychological palette, offering a nuanced portrait of artist-as-observer, poised between introspection and outward gaze.

Relation to Munch’s Broader Oeuvre

While Munch is celebrated for his vivid oil paintings, his contributions to printmaking are equally significant. Self-Portrait in Moonlight sits alongside other nocturnal prints such as Moonlight (1896) and Self-Portrait at the Easel (1906). Yet this particular image stands apart through its integration of self-portraiture and night imagery. Compared to canvases like The Scream, where color intensifies emotion, this print relies on subtle tonality and line to evoke mood. It presages later Expressionist printmakers—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Käthe Kollwitz among them—who would adopt woodcut for its raw emotional potential.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its release, Self-Portrait in Moonlight attracted attention for its technical innovation and introspective subject. Collectors prized hand-colored impressions for their painterly nuance, while critics lauded Munch’s ability to convey complex mood within the constraints of relief printing. The work influenced early twentieth-century graphic artists who saw in it a model for using minimal means to powerful effect. In modern retrospectives, scholars highlight the print’s role in expanding notions of self-portraiture—showing that identity can be expressed not only through likeness, but through atmosphere and light.

Conservation and Provenance

Original impressions of Self-Portrait in Moonlight are housed in collections such as the Munch Museum (Oslo) and the British Museum (London). Conservationists emphasize the fragility of the lightly inked blue layer, which can fade if exposed to strong light. Paper supports—often thin Japanese vellum—require careful humidity control to prevent warping. Scientific imaging has revealed Munch’s finger marks in the inking process, offering insight into his hands-on approach. Provenance records trace early impressions through private Nordic collections before acquisition by major institutions in the early twentieth century.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond its art-historical importance, Self-Portrait in Moonlight resonates with broader cultural themes of solitude, creativity, and self-examination. Poets and writers have drawn upon its imagery to evoke the artist’s inner night. Photographers reference its composition when framing human subjects against minimal backgrounds. In contemporary psychology, the work appears in discussions of reflective practice and the role of space and light in mood regulation. Its legacy endures in how it demonstrates the power of pared-down form and subtle color to engage viewers in a dialogue about presence, awareness, and the creative impulse.

Conclusion

Self-Portrait in Moonlight stands as a testament to Edvard Munch’s genius in fusing technical innovation with profound psychological insight. Through a delicate interplay of moonlit hues, bold outlines, and evocative composition, Munch captures the artist’s dual role as observer and participant in the nocturnal world. The print invites us into a contemplative realm where identity unfolds in light and shadow, affirming the enduring capacity of art to reflect the depths of human experience.