Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

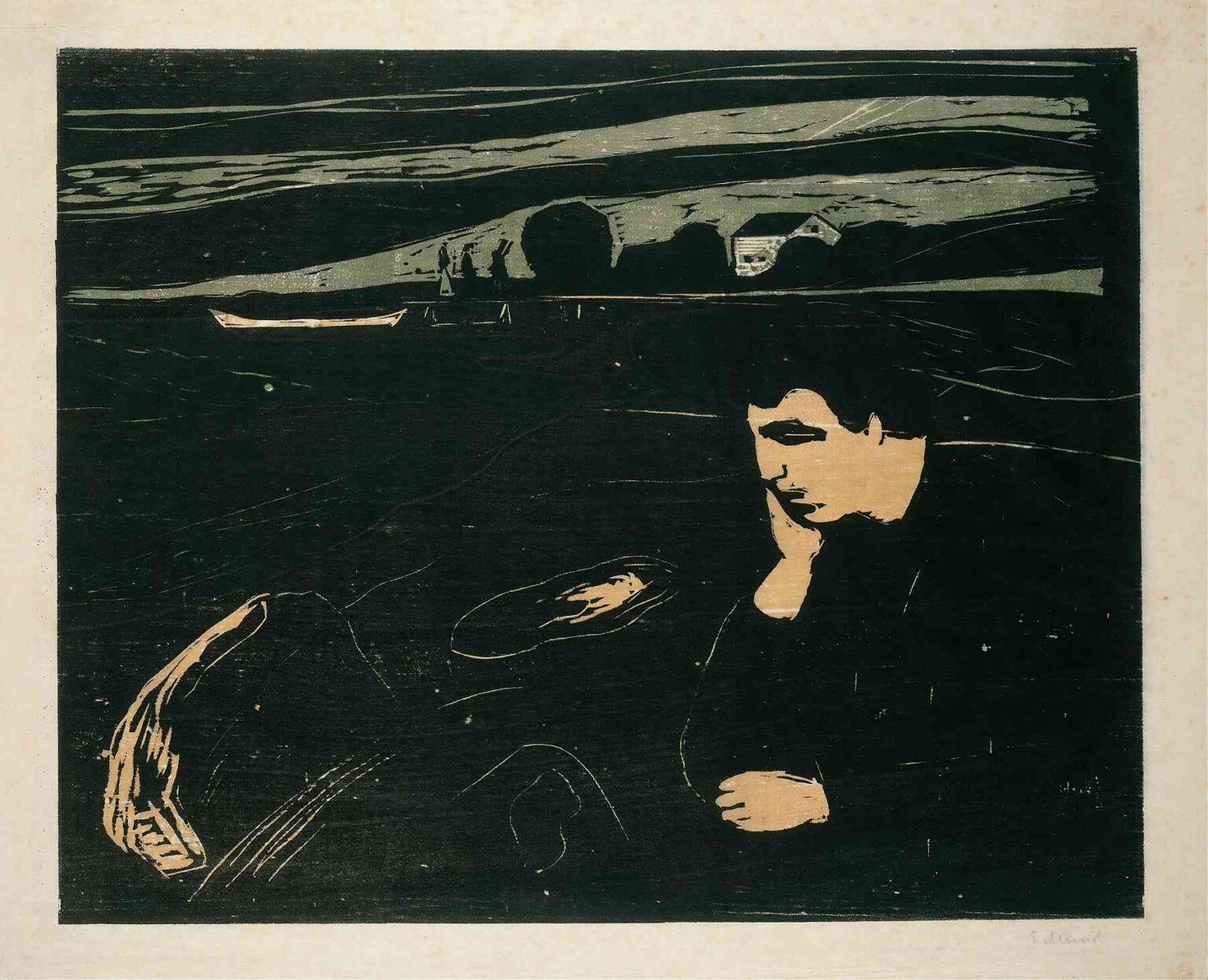

“Melancholy III” stands among Edvard Munch’s most poignant explorations of existential solitude and emotional introspection. Executed as part of his celebrated Melancholy series, this woodcut print distills the artist’s preoccupation with inner turmoil into a spare, almost meditative composition. A lone figure sits on a jutting shoreline, head cradled in hand, gazing out toward a distant boat and rolling hills. Although seemingly simple in execution, the work resonates with layered symbolism, technical innovation, and a profound sense of psychological depth. In this analysis, we will examine how Munch transforms an everyday scene into a universal allegory of longing, anxiety, and the human condition.

Historical and Biographical Context

By the late 1890s, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had already established himself as a leading voice of Symbolism, marked by canvases such as “The Scream” (1893) and “Anxiety” (1894). During this period, personal tragedy—most notably the successive deaths of his mother and sister—intensified his focus on themes of grief, isolation, and psychic disturbance. Relocating intermittently between Kristiania (now Oslo) and Berlin, Munch absorbed influences from German and Norwegian avant-garde circles, deepening his interest in printmaking as a means of disseminating his ideas more broadly. “Melancholy III” emerges from this fertile junction of artistic innovation and emotional vulnerability, reflecting Munch’s determination to probe the depths of human feeling through simplified forms and evocative contrasts.

The Melancholy Series and Its Evolution

Munch’s Melancholy series comprises multiple versions—paintings, lithographs, and woodcuts—created between 1894 and 1902. Each iteration revisits a similar subject: a solitary figure confronting the vastness of sea and sky. While earlier versions lean more heavily on painterly detail, “Melancholy III” strips the scene to essential shapes and tones. This progressive distillation enriches the work’s expressive power: by paring down visual information, Munch encourages viewers to project their own emotional narratives onto the figure. The woodcut’s sparing use of black and the pale ground heighten the sense of void and introspection, making “Melancholy III” both a culmination of the series’ thematic arc and a turning point toward greater formal abstraction.

The Role of Landscape in “Melancholy III”

Landscape in this print is far more than a backdrop; it becomes a partner in the figure’s emotional state. The undulating hills above the horizon line evoke both sheltering womb and looming barrier, while the flat expanse of water suggests an emotional chasm to be crossed. The horizontal bands of tone—dark water, lighter shoreline, mid-tone hills—establish a rhythmic structure that propels the eye across the composition. Yet these bands also feel confining, as if the figure is hemmed in by nature itself. In Munch’s hands, landscape transcends mere setting to act as a mirror for inner life, its rhythms echoing the ebb and flow of melancholy itself.

Composition and Spatial Arrangement

Munch positions the figure off-center, in the lower right quadrant, creating an inward pull toward the sitter’s thoughtful pose. The outstretched shoreline beneath the figure’s feet extends diagonally into the composition, guiding the viewer’s gaze toward the small, solitary boat on the left. This dynamic counterpoint between figure and vessel underscores the tension between stasis and movement, contemplation and potential escape. The high horizon line compresses the pictorial space, intensifying the isolation of the human presence. Negative space envelops the scene, amplifying the visual weight of the printed shapes while underscoring the emptiness that the figure confronts.

The Use of Negative Space

Negative space is central to “Melancholy III.” Munch allows vast swaths of uninked paper to define form as much as the black ink itself. The figure emerges from the void in a single silhouette, head, shoulders, and arm delineated by absence rather than line. Similarly, the distant boat and shoreline are carved out by the paper’s pale tone. This interplay of black and blankness creates a haunting sense of simultaneous presence and absence: we see the figure, yet feel the emptiness that surrounds him. The tension between filled and unfilled areas invites viewers into a meditative space, where suggestion replaces explicit detail and the imagination completes the narrative.

Color Palette and Tonal Contrast

Though monochrome, the print exploits the full expressive range of black ink against creamy paper. The richest blacks define the water’s surface and the figure’s clothing, while intermediate grays—achieved through hatching and varied pressure—model the distant hills and sky. Light areas, where the paper remains exposed, articulate the boat, the figure’s hand, and highlights in the water. This binary palette heightens the work’s stark emotional tenor: the line between light and shadow feels almost moral, suggesting the fragile balance between hope and despair. By limiting chromatic distraction, Munch focuses our attention on form, gesture, and the inherent drama of tonal interplay.

Technique and Medium

Munch’s choice of woodcut printmaking for “Melancholy III” reflects his innovative spirit. He adapted traditional relief techniques to serve his expressive goals, carving broad, sweeping shapes rather than intricate details. The visible grain of the woodblock enriches the surface texture, adding organic irregularities that echo the natural world depicted. Munch’s method often involved inking the block unevenly and wiping selectively, producing subtle tonal gradations uncommon in conventional woodcuts. This painterly approach to printmaking allowed for greater nuance of mood and facilitated wider circulation of his imagery, aligning with his ambition to reach a broader audience.

Symbolism and Motifs

The central motif of a lone, seated figure is rich with symbolic resonance. The posture—head propped on hand—evokes classical personifications of Melancholy and Melpomene, the muse of tragedy. The distant boat, small on the horizon, can signify hope, escape, or existential distance: it floats just beyond reach, beckoning yet unattainable. The empty water represents both a barrier and a mirror, reflecting the figure’s state of mind even as it remains inscrutable. Hills in the background recall the archetype of the threshold or horizon of possibility, reinforcing the tension between remaining and moving on. In unifying these elements, Munch creates a symbolic tableau of emotional exile.

Psychological Themes and Emotional Resonance

“Melancholy III” epitomizes Munch’s lifelong engagement with the psyche. The figure’s anonymity—features obscured—transforms him into everyman, a universal vessel of introspection. The scene embodies a moment of acute self-awareness, where the mind drifts between rumination and yearning. By isolating the figure in a minimal environment, Munch externalizes internal states: the void becomes a visible form of the mind’s emptiness. This externalization foreshadows Expressionist strategies, wherein landscape and figure merge to convey subjective experience rather than objective reality. The resulting emotional resonance is uncanny in its familiarity: viewers recognize their own moments of solitude in the sitter’s silent vigil.

Relation to Munch’s Broader Oeuvre

While Munch’s painted works often feature bold color and dramatic lines, his prints reveal a parallel exploration of form and contrast. “Melancholy III” connects to earlier paintings such as “Moonlight” (1895) and “Dancer by the Water” (1896), where water and shore become stages for emotional revelation. Yet the woodcut’s austerity represents a crystallization of Munch’s pictorial concerns: here, narrative is subordinated to mood. This emphasis on mood over story aligns him with modernists like Wassily Kandinsky and Egon Schiele, who would likewise seek abstraction to capture psychic realities. In this sense, “Melancholy III” serves as both a culmination of Munch’s Symbolist phase and a vital precursor to twentieth-century Expressionism.

Reception and Influence

Initially reproduced in avant-garde journals and limited print editions, “Melancholy III” garnered critical attention for its innovative handling of relief technique and emotional directness. Collectors and fellow artists admired Munch’s ability to imbue a simple image with such narrative ambiguity. The print influenced German Expressionists in Dresden and Berlin, who embraced the power of stark contrasts and personal symbolism. In subsequent exhibitions, Munch’s graphic work earned renewed interest, shaping critical assessments of his versatility. Today, scholars view “Melancholy III” as a landmark in the history of printmaking, illustrating how technical experimentation can amplify psychological depth.

Conservation and Provenance

Original impressions of “Melancholy III” reside in major institutions including the Munch Museum (Oslo) and the Museum of Modern Art (New York). Conservation records highlight the delicate nature of the thin Japanese-style paper Munch often favored, necessitating careful climate control to prevent embrittlement and ink flaking. Infrared reflectography and microscope analysis reveal Munch’s intentional variations in ink density, testifying to his hands-on approach during printing. Provenance trails show the print passing through private European collections before entering public holdings in the early twentieth century, attesting to its lasting appeal among collectors and curators.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond its place in art history, “Melancholy III” resonates with universal experiences of solitude and introspection. Its imagery has appeared in literary contexts—illustrating themes of alienation in turn-of-the-century novels—and in contemporary psychology writings exploring visual metaphors for depression. Filmmakers and photographers have echoed its composition to convey emotional stasis, while contemporary artists reference its spare elegance in installations about mental health. As discussions around vulnerability and emotional well-being gain prominence, Munch’s print retains fresh relevance, demonstrating how art can bridge historical and contemporary understandings of the human psyche.

Conclusion

“Melancholy III” exemplifies Edvard Munch’s mastery of reducing complex emotion to elemental form. Through judicious use of black and blank space, fluid composition, and symbolic motifs, Munch crafts an image that speaks to the universality of melancholy. The woodcut’s technical innovations and psychological depth mark it as a pivotal work in both Munch’s career and the broader trajectory of modern art. Over a century after its creation, “Melancholy III” continues to engage viewers, inviting them to confront the silent vastness within and beyond themselves.