Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Auvers-sur-Oise and the Closing Chapter of Van Gogh’s Life

When Vincent van Gogh arrived in the riverside village of Auvers-sur-Oise on 20 May 1890, he carried both fragile optimism and the weight of a decade’s psychic turbulence. Paris lay only an hour away by train, yet Auvers offered the pastoral calm his doctors prescribed after a year of confinement in the asylum at Saint-Rémy. In the seventy brief days before his death, Van Gogh produced more than seventy paintings, each one a distillation of urgency and lucidity. “Girl in White” dates from this incandescent final stretch—probably June 1890—when ripening wheat fields encircled the village and the artist felt compelled to record every nuance of a landscape that mirrored his own oscillation between hope and despair.

The Unknown Sitter: A Study in Quiet Poise

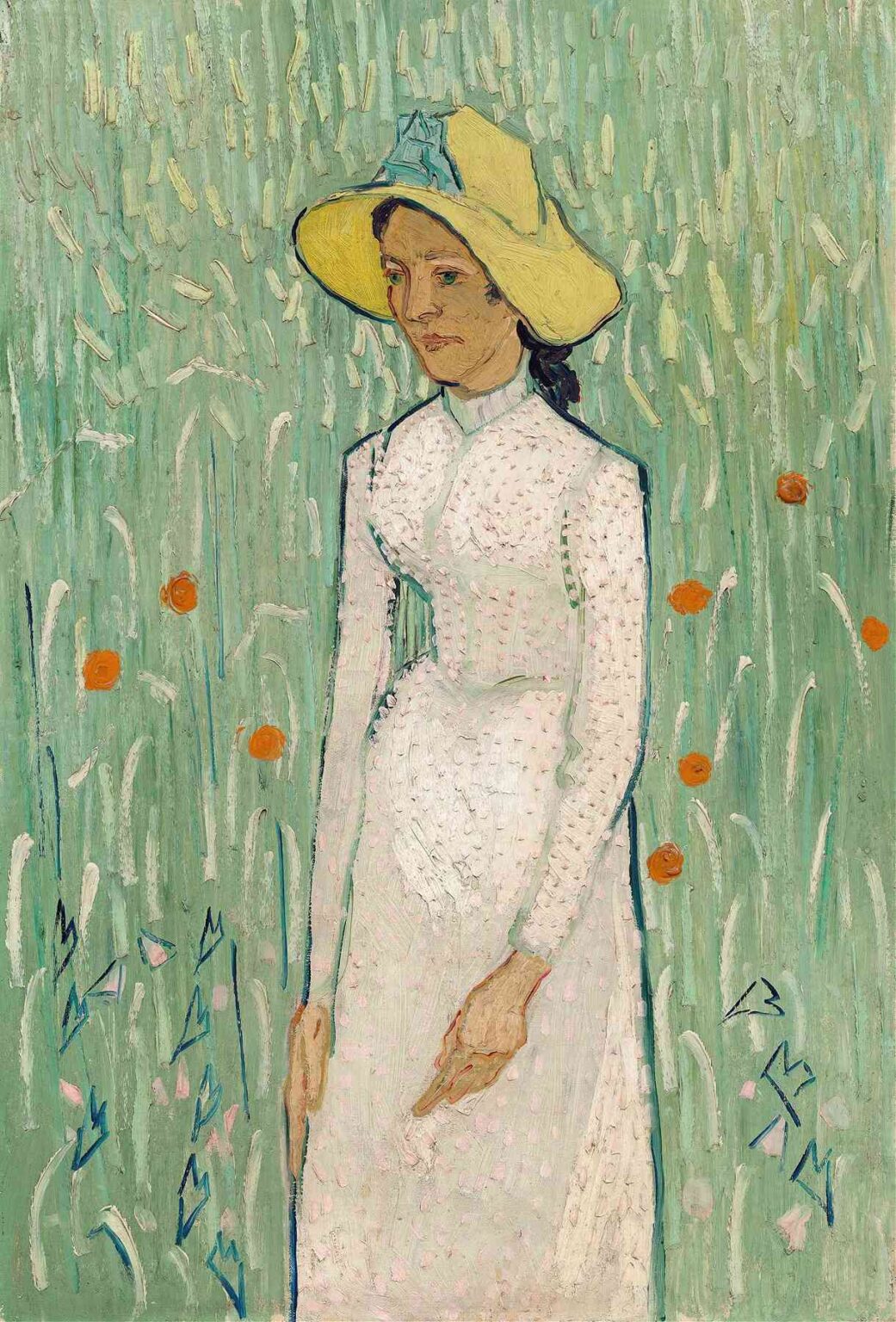

Unlike portraits in earlier periods, in which Van Gogh often named his models, the identity of the young woman in “Girl in White” remains undocumented. She might have been a farmer’s daughter, a domestic servant at the inn where he lodged, or simply a passer-by whose posture captured his attention. Her anonymity turns the painting into a universal meditation on youthful introspection. Clad in a modest high-necked dress, she stands motionless amid swaying wheat and scattered poppies, her downcast eyes suggesting self-containment rather than melancholy. The hat—broad-brimmed straw trimmed with a blue‐gray ribbon—signals rustic practicality more than fashion, grounding the portrait in the rhythms of agricultural life that framed Van Gogh’s final weeks.

Composition: Vertical Tension and Figure–Ground Dialogue

The canvas measures approximately 66 × 41 cm, a deliberately narrow format that elongates the figure and forces a subtle tension between vertical lines and the subject’s stillness. Van Gogh positions the girl slightly left of center so the rising stalks of wheat can cascade behind her, amplifying a sense of movement she does not share. A zig-zag of dark contour lines encircles her silhouette, separating flesh and fabric from background yet also binding them in rhythmic counterpoint—an approach indebted to Japanese ukiyo-e prints he collected in Arles. Because the foreground wheat tips echo the subtle slouch of her shoulders, the composition vibrates with calligraphic repetition, making the entire surface feel choreographed even though nothing overtly happens.

Chromatic Strategy and Emotional Temperature

For a painter celebrated for blazing complementary contrasts, Van Gogh limits his palette here to whisper-quiet harmonies. The field glows in cool celadon and mint, worked wet-into-wet so that individual strokes melt into seamless tonal gradients. Against this sea of greens, the girl’s dress appears almost gray-white, yet tiny rose-colored dabs fleck the bodice and sleeves, adding body heat to a composition that might otherwise feel spectral.

Only two accents break the chromatic hush: the cadmium-orange poppies and the straw-yellow brim of the hat. Their strategic placement functions less as color-field fireworks than as subtle pivots that guide the viewer’s eye in a gentle diagonal from lower left to upper right, echoing the direction of the sun’s fall across a midsummer field. In effect, Van Gogh paints not just a figure but the low hum of an atmosphere, expressed chromatically rather than descriptively.

Brushwork: Calligraphy of Seeds and Stitches

Close inspection reveals a surface alive with texture. In the background, Van Gogh draws each wheat stalk with a single wrist-flick, letting the brush skid so paint gathers along one edge of every stroke, like wind-slanted grass. These marks are vertical yet broken, denying classical perspective in favor of a tapestry-flat plane. The poppies are single dabs of thick orange impasto, still carrying the imprint of hog-bristle.

The girl’s dress, by contrast, is built from ranked comma-shaped touches of white and pale pink that follow the curve of her torso like seed stitches in embroidery. This granular surface catches incident light, lending the garment a flicker reminiscent of pointillist technique without its rigidity. Around the outline, Van Gogh draws a single assertive contour, almost cartoon-like, then lets interior strokes breathe freely. The result is a portrait that toggles between sculptural solidity and optical shimmer—a plastic rendering of form dissolving in light.

Light and Spatial Ambiguity

Traditional portraiture locates its sitters in carved-out three-dimensional space, but Van Gogh spoonfully compresses depth until figure and field share one pictorial plane. There is no cast shadow, no horizon line, no atmospheric perspective to situate the girl metrically inside nature. Instead, depth is intimated through the overlap of strokes and the slight inflection of darker greens behind her head, giving the illusion that she stands a pace or two forward. This shallow relief invites viewers to read the painting simultaneously as landscape and decorative panel—a duality that anticipates modernist flatness.

Symbolism of Wheat, Poppies, and White Attire

In Van Gogh’s late iconography, wheat fields symbolize the eternal cycle of labor, nourishment, and mortality. Here, the grain is still green, not yet gold—an image of potential rather than harvest, aligning eloquently with the sitter’s youth. Poppies, their petals soon to scatter, whisper of transience. Their flaming hue against the muted field introduces a botanical memento mori, though rendered so gently it never lapses into didacticism.

White, in nineteenth-century color symbolism, carried layers of meaning: purity, modesty, even spiritual aspiration. Yet Van Gogh’s handling of the hue—flesh warm beneath thin paint, fabric animated by clots of impasto—rescues the dress from pious cliché. Instead, white performs a painterly function: it reflects surrounding greens and oranges, forging chromatic communion between human and habitat.

Psychological Resonance: Stillness amid Motion

Although the standing figure is physically static, the painting hums with kinetic energy. Jagged wheat strokes and hovering poppies suggest a breeze, yet her slight forward cant implies she is weighing an inner question rather than enjoying the scenery. This contrast—nature in flux, human consciousness stilled—dramatizes the existential gap Van Gogh often contemplated in letters to his brother Theo. He wrote of longing to lose himself in nature even as he remained excruciatingly self-aware; “Girl in White” visualizes that tension.

Relation to Other Late Portraits

During the Auvers period, Van Gogh painted roughly a dozen portraits, including “Adeline Ravoux,” the “Portrait of Dr. Gachet,” and several images of children. Compared with those, “Girl in White” is unusually frontal and refined. The elaborate patterned wallpaper behind Dr. Gachet, for instance, is here replaced by a living pattern of vegetation. Likewise, the introspective gloom of “Adeline Ravoux” yields to a muted serenity; if “Adeline” is a nocturne, “Girl in White” is a dim morning reverie. Such variety underscores Van Gogh’s refusal to settle on a single psychological key in his final weeks, exploring instead a spectrum of emotional timbres through portraiture.

Provenance and Museum Journey

After Van Gogh’s death, the painting passed to his sister-in-law Jo van Gogh-Bonger, whose stewardship of the estate shaped the artist’s posthumous fame. By the early twentieth century, it joined several private European collections before crossing the Atlantic. Since 1955 it has resided in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., where its refined palette and meditative aura distinguish it among the museum’s post-Impressionist holdings. Each shift of ownership marked a new chapter in Van Gogh’s ascendance from fringe painter to cultural touchstone, and “Girl in White” has frequently featured in retrospectives that map his final oeuvre.

Conservation and Technical Insights

Infrared reflectography shows no substantial under-drawing, indicating Van Gogh drafted directly with paint—a habit born of speed and confidence. X-ray fluorescence confirms a limited pigment array: lead white, chromium oxide green, viridian, chrome yellow, and cadmium orange, all typical of his Auvers palette. Microscopy of the impasto reveals ragged peaks where brush hairs lifted away, corroborating accounts of his quick, nervous touch. The painting’s relatively stable condition, with only minor craquelure in thicker strokes, testifies to the robust quality of his late-period canvases, which often used coarser linen and thicker priming than those from Arles.

Critical Reception and Interpretive Evolution

Early twentieth-century critics, still acclimating to Van Gogh’s audacious color, praised the canvas for “restrained lyricism”—a virtue they believed offset his more “violent” works. Mid-century formalists highlighted its flattened depth as a proto-modernist experiment. Feminist art historians later interrogated the sitter’s anonymity, reading the painting as symptomatic of patriarchal invisibility. Contemporary scholarship, drawing on neuroaesthetics, links the rhythmic brushwork to embodied viewer response: eye-tracking studies show that spectators follow the same zig-zag paths Van Gogh’s hand once carved, forging an uncanny kinesthetic bond with the artist’s gesture. Each interpretive layer enriches, rather than exhausts, the painting’s quiet power.

Modern Resonance and Cultural Afterlives

Beyond academia, “Girl in White” circulates widely in visual culture—book covers, lifestyle magazines, even fashion color palettes reference its sage greens and powdered pinks. Digital reproductions flood social media feeds each summer, often captioned as tributes to calm or mindfulness. Such ubiquity risks trivialization, yet it also proves the work’s adaptable emotional bandwidth: viewers detect in the girl’s gaze whatever nuance—solitude, resilience, anticipation—they themselves carry. In this portability lies Van Gogh’s modern relevance: a capacity to mirror the inner climates of successive generations without forfeiting his own.

Conclusion: An Intimate Epitaph in Verdant Tones

In “Girl in White,” Van Gogh compresses landscape, portrait, and silent narrative into a single, slender panel. The result is neither grand statement nor sentimental vignette but a poised meditation on arrested time: a breeze cuts across wheat, poppies flare and fade, and a young woman pauses at the edge of adulthood, immune for a moment to both turmoil and relief. Through chromatic restraint and nervous brushwork, Van Gogh translates the hum of a June afternoon into paint—an offering of stillness from an artist whose mind rarely stilled.

Seen today, the canvas reads as a paradoxical epitaph: created in feverish haste, yet broadcasting calm; rooted in a specific summer, yet timeless. It asks viewers to listen closely, for beneath the pale dress and muted field lies a pulsing heartbeat—Van Gogh’s own, counting down the weeks while pouring itself into color, line, and the unspoken depths of a girl who remains forever young amid eternal grass.