Image source: artvee.com

Vincent van Gogh painted “Adeline Ravoux” in June 1890, a scant six weeks before his death. Freshly discharged from the asylum at Saint-Rémy, he moved north to the rural village of Auvers-sur-Oise to be closer to his physician-friend Paul Gachet and within day-trip distance of Paris, where his brother Theo lived. The pace of Van Gogh’s production in those final seventy days is legendary—more than seventy canvases that channel a turbulent mix of hope, exhaustion, and creative urgency. “Adeline Ravoux” belongs to this late, incandescent burst. Its terse palette and compressed energy mirror both the artist’s fragile optimism about a new beginning and his gnawing fear that another psychological collapse lurked nearby.

The Sitter: Introducing Adeline Ravoux

Adeline was the shy, adolescent daughter of Arthur Ravoux, proprietor of the modest inn where Van Gogh lodged. She was fourteen, poised awkwardly between childhood and adulthood. Contemporary accounts describe her as reserved, with a quiet dignity that evidently intrigued the painter. Van Gogh saw in Adeline a still point amid the din of the inn’s taproom, a quality he immortalized through a profile view that resists direct engagement yet emanates silent intensity. Unlike his portraits of peasants or laborers from Nuenen, Adeline is not idealized social type but individual—her downcast gaze and compressed lips hint at an interior life still forming.

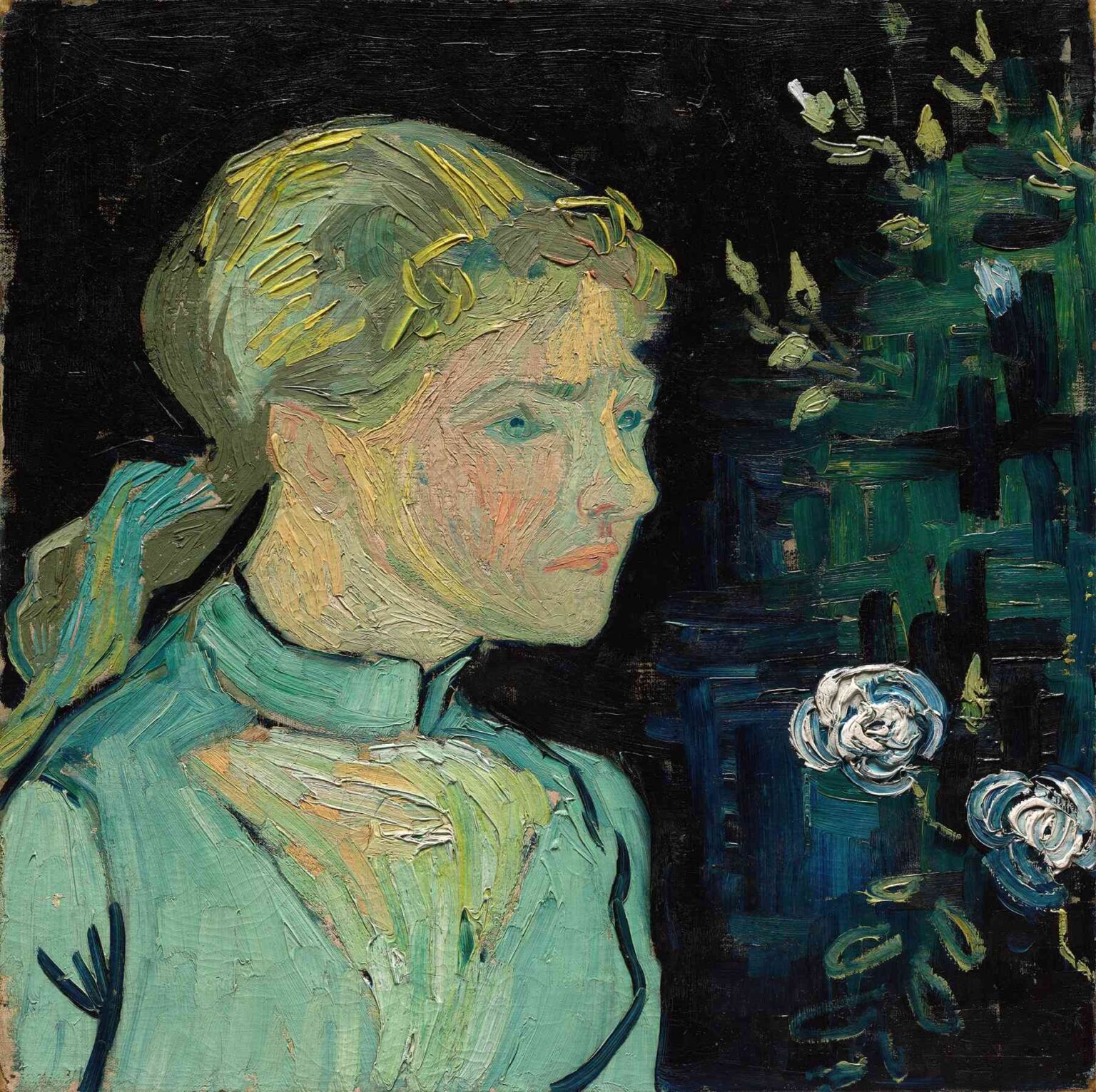

Composition: Severe Profile, Lyrical Counterpoint

Van Gogh sets the young sitter in rigid profile against a pitch-black void, anchoring her at left while allowing the right half of the canvas to breathe with loosely suggested foliage and three white roses. The arrangement feels almost classical: the line of Adeline’s nose echoes the longest diagonal of the rectangle, and the horizontal that cuts through her collarbone aligns with the bottom of the floral cluster, forging a subtle geometric grid. Negative space is as eloquent as pigment; the inky background pushes the pale figure forward, intensifying her presence. The rightward orientation of her gaze propels the viewer’s eye toward the roses, creating narrative tension even in stillness.

Palette and Chromatic Psychology

Narrow tonality defines the work. Van Gogh confines himself to cool sea-greens, viridian, turquoise, and thin inflections of ochre in the hair and flesh. The chromatic austerity distances this portrait from the blazing yellows and cobalt skies of Arles, underscoring the painter’s darker psychological climate. Yet the color choices are not purely somber. By pairing cool greens with pearly whites, he evokes purity and the tentative promise of renewal—sentiments frequently attached to adolescent sitters in late-nineteenth-century portraiture.

Key interaction of hues

The emerald ribbon binding Adeline’s hair repeats in the botanical forms, linking human and floral domains in a closed chromatic loop.

Flecks of chrome yellow in the highlights counteract the greens, adding pulse without disrupting tonal unity.

Brushwork and the Language of Impasto

As always, Van Gogh’s brushwork is content in itself. Thick, dragged strokes model Adeline’s cheek and forehead; directional ridges march across her bodice like geological strata. The paint is laid on wet-into-wet, giving edges a soft, wavering vibration—note how the shoulder melts into background. In the roses, impasto ridges render petals in sculptural relief, each stroke turned slightly to catch light. Such bravura technique grants otherwise ordinary subjects an emblematic charge; the portrait pulses between materiality (the movement of oil across canvas) and immateriality (the sitter’s introspective mood).

Light, Shadow, and Spatial Depth

No explicit light source glimmers; instead, Van Gogh builds luminosity by juxtaposing thick, opaque highlights against matte, absorbent blacks. The absence of cast shadows flattens the figure, aligning it with Japanese woodblock aesthetics that long captivated him. Spatial depth arises primarily through color recession—greens recede, whites advance—rather than Renaissance modeling. This deliberate shallowness corners the viewer into confronting the painting’s surface, calling heed to paint as paint even while musing on the sitter’s psyche.

Roses as Silent Symbols

The trio of white roses may at first seem incidental, but Van Gogh rarely painted without coded resonance. White roses traditionally signify innocence tinged with melancholy—a perfect metaphor for Adeline’s threshold state. Moreover, in Van Gogh’s personal iconography, flourishing plant forms often symbolize cycles of life and hope. Contrasted against an enshrouding black backdrop, the blossoms acquire poignant fragility, mirroring the precarious balance of youthful promise and existential uncertainty.

Emotional Narrative and Psychological Insight

The portrait is less an objective likeness than a psychological probe. Adeline’s averted eyes, compressed mouth, and slightly furrowed brow suggest self-consciousness under scrutiny. Yet the profile view also protects her; she withholds full access to her thoughts. For Van Gogh—who wrestled constantly with feelings of acceptance and isolation—this silent reserve likely resonated. The painting becomes a dialog between two sensitivities: the teenage model negotiating new social visibility and the artist confronting his own isolation within a bustling inn.

Relation to Van Gogh’s Late Portraiture

During his Auvers period, Van Gogh produced portraits of Dr. Gachet, Gachet’s daughter, and several local children. Compared with those works, “Adeline Ravoux” is sparer, almost austere. Where the “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” shimmers with ornamental pattern, Adeline’s background is aggressively pared down. Van Gogh seems to be seeking the distilled essence of character, a minimalism that anticipates modernist portraiture by two decades. This severity reflects his admiration for Jean-François Millet’s moral earnestness but also signals a personal shift: fatigue with decorative excess in favor of concentrated emotion.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh’s death, the canvas remained with Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, who tirelessly championed Vincent’s reputation. It changed hands among private collectors before entering a European museum collection (now often exhibited in retrospectives of the late works). Each transfer coincided with milestones in Van Gogh’s rising critical stature—from near-obscurity in 1890 to post-Impressionist titan by the 1920s, to market superstar by the late twentieth century. The portrait’s price appreciation is not merely economic trivia; it charts shifting cultural appetites for psychological depth in art.

Conservation and Technical Findings

Recent infrared reflectography reveals no major compositional changes, indicating Van Gogh’s first conception remained intact. X-ray fluorescence shows a relatively limited pigment set—lead white, chrome yellow, viridian, ultramarine, and small traces of red lake—consistent with letters in which he lamented dwindling funds for materials. Conservators note moderate craquelure in thicker impasto regions, typical of his rapid drying technique. Varnish was sparingly applied, in keeping with Van Gogh’s skepticism toward glossy finishes he felt dulled color intensity.

Critical Reception Through the Decades

Early reviews of Van Gogh’s portraits oscillated between fascination and discomfort. Critics praised color daring yet questioned draftsmanship. By the mid-twentieth century, scholars like Meyer Schapiro saw in works such as “Adeline Ravoux” an existential gravitas akin to contemporary literature; later feminist readings explored the sitter’s emergent identity within patriarchal settings. Most recent discourse frames the portrait through neuroaesthetic lenses, examining how viscous brushwork triggers embodied viewer responses. In each epoch, the canvas has answered cultural longings—to witness authenticity, vulnerability, or the neurological roots of empathy.

Echoes in Modern and Contemporary Art

The portrait’s directness forecast trends later explored by Expressionists and Fauves: Egon Schiele’s raw adolescent sitters, Matisse’s economical line. Even contemporary painters like Marlene Dumas, who probes psychological fragility through simplified form, owe an unspoken debt. Beyond the studio, “Adeline Ravoux” circulates in pop culture—appearing on book covers, inspiring fashion editorials that replicate its seawashed palette, and featuring in documentaries as emblem of Van Gogh’s humanist focus.

Personal Reflection and Interpretive Synthesis

Standing before “Adeline Ravoux,” viewers are struck by how few elements can evoke such complexity. A band of green, a sliver of yellow, three terse roses, and silence—yet from this sparseness emerges a symphony of questions: What apprehensions flicker behind her pale lashes? Did Van Gogh glimpse in her uncertainty a mirror of his own? The painting’s austere beauty rests on that shared vulnerability, suspended forever in a heavy quiet that feels both consoling and urgent. In tracing the ridges of paint, we sense the artist’s heartbeat; in following Adeline’s gaze beyond the frame, we enter a realm where potential and loss coexist.

Ultimately, “Adeline Ravoux” exemplifies the paradox at the core of Van Gogh’s art: a boundless empathy expressed through uncompromising formal economy. It is a portrait of a single young girl and, simultaneously, of restless modern consciousness, still searching for light amid encroaching night.