Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

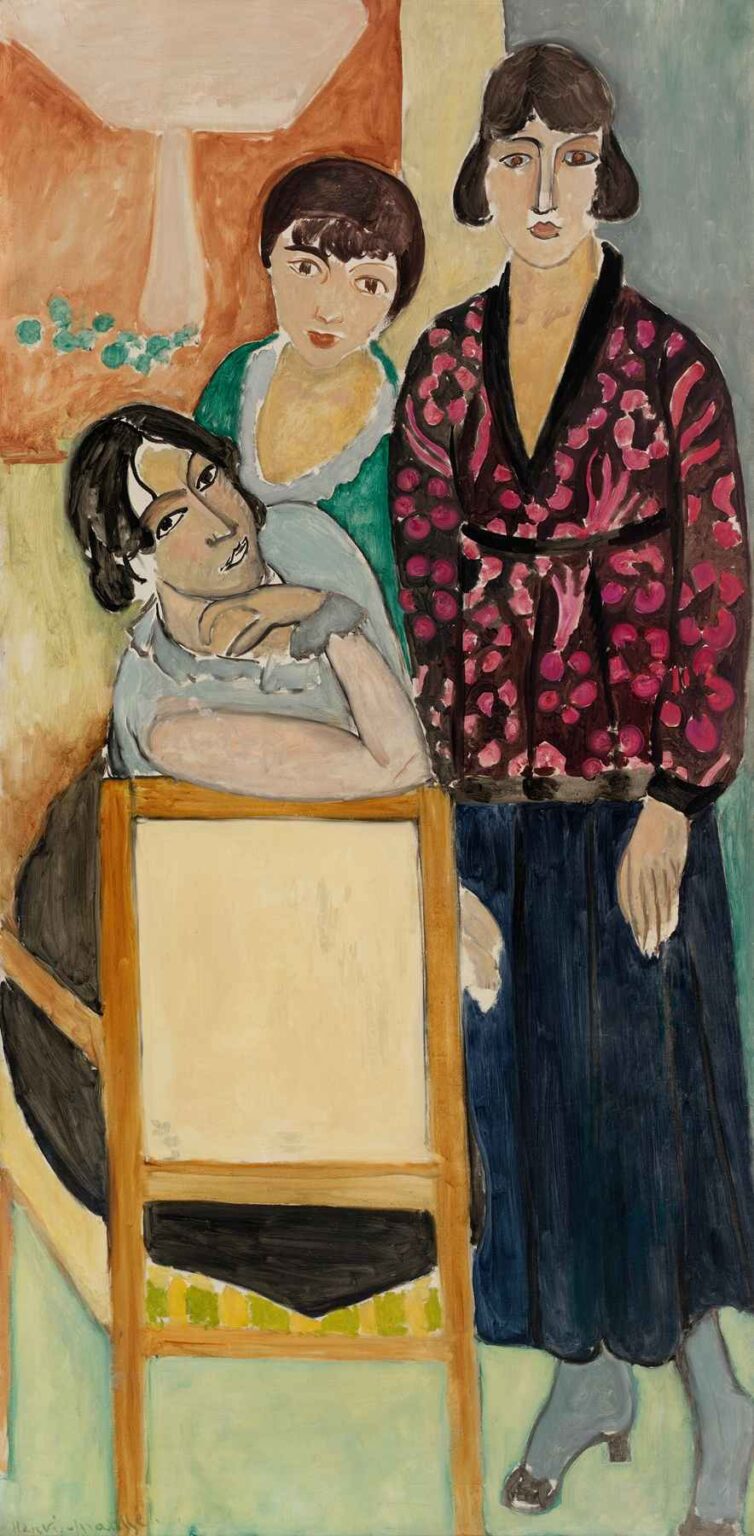

Henri Matisse’s Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” (1917) marks a high point in the artist’s wartime exploration of decorative harmony, familial intimacy, and flattened pictorial space. Painted in the closing year of World War I, this large‐scale canvas is neither a grand historical statement nor an overtly exotic tableau. Instead, Matisse turns inward, portraying three young women—seated and standing—around a softly veined, rose‐colored marble tabletop. With broad planes of color behind them and sumptuous patterns upon their clothing, the sisters inhabit a shallow interior that feels at once tenderly domestic and boldly modern. Over the next sections, we will examine how Matisse integrates historical context, compositional rigor, chromatic invention, spatial flattening, expressive brushwork, psychological depth, thematic resonance, and his own evolving artistic trajectory into a seamlessly unified work of art.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1917, Europe was still mired in the devastation of the Great War, and Matisse himself had interrupted his artistic pursuits to serve briefly as a Red Cross orderly. When he returned to the suburb of Garches, outside Paris, he resolved to make art that could provide solace rather than agitation. His early Fauvist canvases, notorious for audacious, non‐naturalistic color, had already given way to a more tempered yet still intensely decorative approach. Matisse realized that color could heal by restoring a sense of order and beauty, and he began to focus on domestic interiors, still lifes, and close acquaintances rather than public or mythological subjects. Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” emerges precisely from this climate of reflection and renewal. It is neither a political protest nor a nostalgic retreat; it is a vivid affirmation that intimate scenes, imbued with carefully orchestrated color and pattern, could renew the human spirit in troubled times.

Subject Matter and Setting

At the painting’s heart are three young women, arranged around a rose‐marble tabletop whose subtle pink and gray veins impart a quiet radiance. The figure in the immediate foreground sits, leaning forward with her folded arms resting upon the table. Clad in a pale blue blouse with a softly scalloped collar, she fixes the viewer with a direct, curious gaze. Behind her, the second sister stands slightly to the left, dressed in a vibrant green garment edged with white lace. Her head is tilted, as if in gentle conversation or contemplative listening. To the right stands the third sister, whose dark jacket is patterned with magenta blossoms that seem to float across its surface. She assumes an upright posture and maintains a serene, protective bearing. The background consists of three broad vertical panels—warm apricot on the left, soft lemon in the center, and muted slate‐gray on the right—each panel unadorned except for the subtle texture of brushstrokes. This simplified setting strips away any distracting details of room or environment, allowing the sisters and their rose‐marble table to dominate the viewer’s attention.

Compositional Architecture

Matisse structures the composition around a graceful interplay of verticals and horizontals, overlapped in shallow relief. The seated figure’s torso forms a broad horizontal band that aligns with the marble tabletop, creating a base upon which the standing sisters rise. Their shoulders trace a gentle diagonal from left to right, guiding the eye upward and across. The rhythmic repetition of the three figures—two vertical postures flanking one seated—establishes a subtle triangular arrangement, lending stability to the whole scene. Behind them, the three colored background panels act like decorative frames, each one echoing or contrasting the hues in the sisters’ garments. The marble tabletop itself asserts a semi‐circular arc that softens the verticality and hints at a larger circular motif beyond the canvas’s edge. Rather than receding into deep perspective, these planes overlap gently—table over skirt, figures over panels—creating a tapestry‐like unity in which each element participates equally in the painting’s decorative harmony.

Chromatic Invention and Light

Color in Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” functions as both structure and emotional catalyst. The marble tabletop’s rosy veins mirror the blossoms on the rightmost sister’s jacket, forging an immediate visual link between figure and furnishing. The middle sister’s green dress resonates with minute flecks of foliage implied at the table’s edge. The leftmost sister’s pale blue blouse echoes the cooler slate‐gray panel behind her. Matisse refrains from dramatic modeling; the sisters’ skin is rendered in warm peaches and soft pinks, with subtle shifts in hue suggesting the volume of limbs and torsos rather than forceful chiaroscuro. Instead of pronounced shadows, adjacent color changes—a cooler glaze beneath an arm, a warmer tint on a forehead—convey the effect of diffused daylight, perhaps filtered through a window beyond the frame.

The three background bands—apricot, lemon, and slate—act as discreet color harmonizers, each one selected to resonate with the sisters’ attire and the marble’s blush. The apricot echoing flesh tones, the lemon invigorating the green dress, and the slate‐gray providing a measured counterpoint to the jacket’s magenta blossoms together form a carefully calibrated palette. Hints of coral and chartreuse in the table’s veins and the garment patterns add further chromatic punctuation, animating the scene without disrupting its serene balance.

Spatial Flattening and Decorative Surface

Although clearly depicting a domestic interior, Matisse deliberately flattens spatial depth to focus on surface design. The marble tabletop overlaps the seated figure but casts no realistic shadow; it reads as a decorative plane balanced atop the sisters’ folded arms. The background bands function like wallpaper or textile motifs, each panel’s uniform color serving as a decorative field rather than a receding wall. Overlapping is minimal and nearly schematic—the sisters’ bodies over the panels, the table over the figure—but the illusion of three‐dimensional space dissolves into a series of decorative zones. The painting thus becomes a visual tapestry in which figure, architecture, and furnishing merge into a single, rhythmical surface. This flattening of space exemplifies Matisse’s decorative modernism, where surface rhythm and color relationships outweigh illusionistic depth.

Brushwork and Textural Variation

Matisse’s brushwork in this painting strikes a balance between even color fields and expressive gestures. The background panels are executed in broad, horizontal strokes that leave the weave of the canvas visible, creating a softly luminous field. The marble tabletop receives rhythmic, veined strokes that replicate the stone’s natural pattern without slavish imitation. Garment patterns—particularly the magenta blossoms—are painted with short, calligraphic dashes, each dab retaining the artist’s hand gesture. Flesh areas are glazed in thin, translucent layers, imparting a supple softness to skin. Subtle highlights on collars, cuffs, and lace are registered with fine, almost chalky strokes that stand out against broader passages. This interplay of brushstroke types—flat fields, textural motifs, glazed glimmers—imbues the painting’s surface with tactile richness, even as the overall effect remains decorative.

Psychological Depth and Emotional Tone

Although the composition is decorative, it also conveys poignant psychological nuance. The seated sister’s direct gaze and slight forward lean suggest openness and youthful curiosity. The central sister’s head tilt and softened features evoke empathy and quiet presence. The rightmost sister, with her protective stance and composed expression, embodies calm guardianship. Together, their varied gestures form an emotional dialogue: curiosity, empathy, and stability. The marble table, cold and enduring, anchors their exchange in a domestic ritual of shared presence—perhaps a moment of study, reflection, or conversation. In this sense, the painting captures sisterhood not as a static arrangement but as a dynamic emotional system, where each figure contributes her distinct temperament to the collective harmony.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance

Beyond its formal grace, Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” resonates with thematic layers. The marble table—ancient and enduring—contrasts with the fleeting youth embodied in the sisters’ figures. Yet the table’s rose veins and the floral motifs on the jacket link natural cycles of growth and renewal to the solidity of stone. The sisters themselves, arrayed in garments of blue, green, and magenta, evoke the primary harmonies of nature—water, vegetation, and bloom—while the background panels recall dawn’s apricot sky, midday light, and twilight shadow. In this way, the painting becomes a symbolic meditation on time, continuity, and the restorative power of beauty. Matisse does not construct a narrative but invites viewers into a visual poem, where each element—color, gesture, material—echoes the theme of unity amid difference.

Relation to Matisse’s Oeuvre

Executed the same year as Three Sisters with an African Sculpture, this painting deepens Matisse’s exploration of group portraiture within flattening decorative space. Unlike the earlier work’s exotic reference to African art, Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” remains rooted in the domestic, emphasizing what is closest to the artist’s heart: family, home, and personal ritual. It also anticipates Matisse’s 1920s interiors, where pattern and figure fuse more seamlessly, and his late “gouaches découpées,” where color fields and simple contours become the sole building blocks. In the trajectory of his career, the canvas represents a crucial pivot: the bold chromatic freedom of Fauvism refined into an elegant decorative modernism and a psychologically rich humanism.

Influence and Legacy

Matisse’s integration of familial intimacy, color, and decorative flattening influenced generations of artists and designers. Abstract Expressionists admired his surface authority and color autonomy, seeing in his work a model for how paint could assert its own presence. The Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s drew directly on his tapestry‐like surfaces and the fusion of figure with ornament. Contemporary portraitists continue to reference his group compositions when seeking to balance individuality and unity. In interior design and textile arts, the painting’s palette and spatial organization remain a touchstone for creating harmonious, people‐centered spaces.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” (1917) transcends simple portraiture to become a symphony of color, form, and emotional resonance. Through its masterful composition, harmonized palette, spatial flattening, and expressive brushwork, the painting affirms art’s capacity to bind personal intimacy and universal beauty into a single decorative vision. In the context of wartime weariness and his own search for renewal, Matisse turned to the quiet power of family and domestic objects, transforming them into a testament to color’s healing force. More than a century later, Three Sisters and “The Rose Marble Table” endures as a radiant celebration of human connection, material beauty, and the transcendent potential of painting.