Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Cultural Context

In the first decade of the twentieth century, France was wrestling with a host of political, social, and cultural upheavals. The Dreyfus Affair had deeply polarized French society, pitting republicans, intellectuals, and progressives against conservative, nationalist, and militaristic elements. The rise of labor movements, anarchists, and syndicalists challenged established power structures, while artists and writers looked for new forms of expression. One of the most incendiary publications of this era was the satirical journal L’Assiette au Beurre (1901–1912), which combined biting cartoons, political commentary, and avant-garde illustrations to skewer everything from corrupt politicians to colonial ventures. Félix Vallotton (1865–1925), a Swiss-born painter and printmaker associated with the Nabis and later with bold graphic works, contributed several memorable plates to L’Assiette au Beurre. His 1902 lithograph titled “Ah ! bougre de salaud, tu m’as appelé vache !” epitomizes his ability to marry stark visual economy with savage social critique. In order to appreciate the full force of this image, one must situate it within the fraught political climate of the time, Vallotton’s evolving aesthetic, and the radical ambitions of Caran d’Ache and the journal’s editors.

Félix Vallotton: Life, Influences, and Graphic Turn

Félix Vallotton began his career in the early 1890s as one of the Nabis—a group of post-Impressionist painters including Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard—who sought to renew painting through flat planes of color, decorative pattern, and symbolic content. Vallotton’s early canvases and woodcuts exhibited an interest in psychological tension and domestic drama, often painted with a meticulous attention to line and design. By the late 1890s, however, he turned increasingly to graphic art—woodcuts and lithographs—drawn to their immediacy, reproducibility, and potential for social commentary. In 1899 he published a breakthrough series of provocative woodcuts depicting bourgeois hypocrisy; these works solidified his reputation as a master of black-and-white imagery. His collaborations with L’Assiette au Beurre gave him an outlet for overt political satire, and “Ah ! bougre de salaud, tu m’as appelé vache !” is among his most powerful contributions to the journal’s critique of state violence and social injustice.

Subject Matter and Narrative

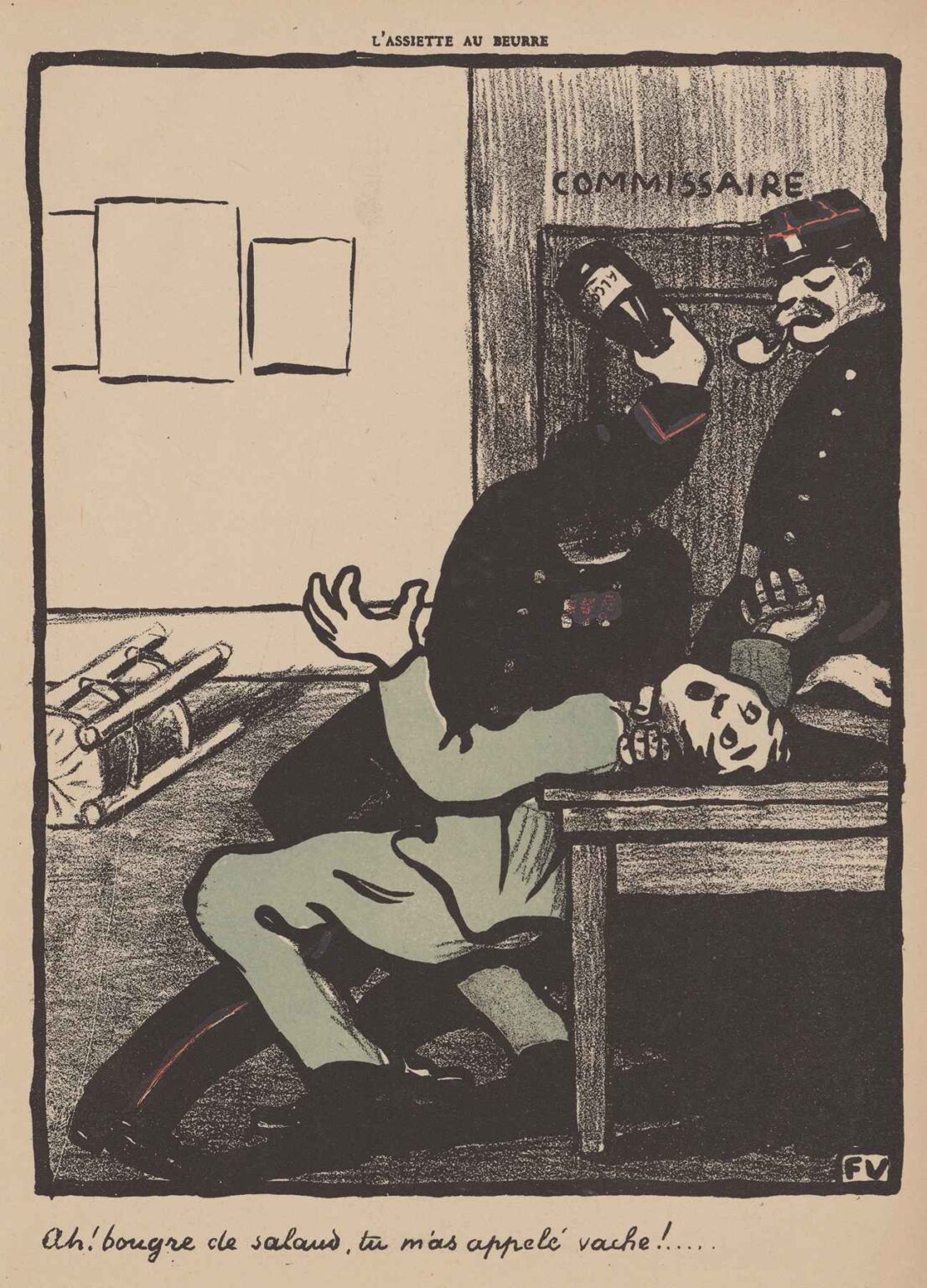

At first glance, the image depicts two figures in a cramped interior: a civilian, slumped over a wooden bench or table, and a uniformed policeman bearing down on him from behind. The victim’s head tilts backward over the edge of the bench, mouth slack and eyes half-open, as though stunned by a blow. The assailant grips a dark, rectangular object—likely a baton or truncheon—raised high, ready to strike again. Above the doorway behind the officer, the word “Commissaire” identifies the setting as a police station or magistrate’s office. Below the scene, the caption reads:

“Ah ! bougre de salaud, tu m’as appelé vache !…”

Translated loosely, it means: “Ah, you rotten bastard, you called me a cow (bitch)!” The irony is merciless: the magistrate’s representative, enraged by an insult and brandishing violence, is himself the transgressor of law and order. The cartoon thus exposes state brutality, lampooning the hypocrisy of officials who equate verbal insult with criminal offense while wielding lethal force with impunity.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Vallotton arranges the space on a shallow, near-vertical plane that flattens the background against the figures. The cropping is tight: the seated man’s bent legs and broken crutch jut in from the left edge, while the officer’s heavy torso and arm fill the right. This claustrophobic composition heightens the sense of aggression and suffocation. The horizontal line of the bench or table provides a base that anchors the victim’s head, forming a right angle with the officer’s raised arm. Diagonal lines—of the victim’s arm flung back, of the crutch on the floor—lead the eye toward the central point of violence: the baton poised to strike. The door frame behind the assailant establishes verticals that echo his imposing stance, further delineating the dual roles of arbiter of order and perpetrator of brutality.

Line, Shape, and Graphic Economy

Vallotton was a master of reductive line. Here, he uses thick, black contours to define bodies, clothing folds, and architectural elements. Unnecessary detail is omitted: the policeman’s hat is indicated by a simple curve and three stripes, while the commissaire’s sign above the door consists of block letters in a rudimentary font. The victim’s features—a fallen jaw, a single eyelid, an open mouth—are rendered with just a few strokes. The crutch behind him appears as a pair of parallelograms connected by slender bars. Negative space functions as much a compositional element as line: the blank beige of the wall emphasizes the stark black of uniforms and the pale green of the victim’s jacket. This graphic economy allows the drama to radiate from minimal visual cues, ensuring that no detail distracts from the central act of violence.

Tonal Contrast and Registered Color

The lithograph employs three main tonal values: deep black for uniforms and outlines, pale ochre for walls and floor, and a muted green-gray for the victim’s clothing. The limited palette underscores the moral binary at play: black for the state’s oppressive force, pale hues for the defenseless citizen. The victim’s jacket in greenish-gray marks him as neither criminal nor hero but as an everyman dragged into the gears of state machinery. The stark contrast between black and light also evokes the chiaroscuro tradition—an artistic tool for dramatizing crime and punishment—while remaining resolutely modern in its flat rendering and lack of gradient shading.

Thematic Resonances: Authority and Impotence

At its core, Vallotton’s image indicts the arbitrary exercise of authority. The victim is clearly powerless: his broken crutch at left hints at injury or accident, yet the policeman interprets his weakness as insolence. The man’s slumped posture and raised hand imply a futile attempt at defense or appeal, while the commissaire’s glare and raised baton demonstrate the official’s contempt for due process. By labeling the scene with the commissaire’s office, Vallotton underscores that the very seat of justice has become a site of injustice. This resonates with broader critiques of the Third Republic’s state apparatus, especially in the wake of repressive responses to strikes, protests, or Dreyfusard demonstrations. The cartoon thus functions as radical political commentary: exposing how the letter of the law is bent to serve the whims of those in power.

The Power of Insult and Reaction

The caption’s reference to being called “vache” (cow or bitch) is significant. In French colloquial speech, vache connotes baseness or cruelty when applied to a person, yet it remains merely an insult—no crime. The commissaire assumes the mantle of offended dignity and retaliates with state-sanctioned violence. This juxtaposition of word and deed underscores Vallotton’s point: physical assault, theft of liberty, and mental anguish are trivialized, while a verbal slight becomes a capital offense. It is a satirical inversion of justice that raises questions about courage, rhetoric, and the disproportionate use of force. The image invites viewers to consider how authority figures manipulate minor provocations to justify brutality, thereby maintaining a climate of fear and obedience.

Artistic Influences and the Woodcut Tradition

Though Vallotton produced both woodcuts and lithographs, his style in this plate recalls the bold black-and-white aesthetic of classic German Expressionist printmakers and Japanese ukiyo-e artists. The heavy outlines and flat planes of color echo Hokusai’s portraits, while the psychological intensity and economy of line anticipate the work of later Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Vallotton’s early Nabis training—in which flat color fields and linear patterning were prized—also informs the image’s surface. Yet he adapts these lessons to political satire, demonstrating how modern print media could harness avant-garde visuals for social critique. The image sits at the intersection of fine art and political cartoon, a hybrid that allowed Vallotton to reach wider audiences beyond the gallery.

Context within L’Assiette au Beurre

L’Assiette au Beurre, under the direction of Samuel Sigismond Schwarz, differentiated itself from other satirical weeklies through full-page illustrations, high-quality paper, and contributions by leading artists. Each issue had a thematic focus—militarism, prostitution, colonialism—and invited a roster of illustrators to provide singular plates. The 1902 issue containing Vallotton’s plate targeted the police and judicial system. Contemporary readers would have seen this image alongside other scathing lampoons of state dysfunction. The magazine’s radical reputation contributed to its demise in 1912, after accusations of incitement and censorship pressures. “Ah ! bougre de salaud…” stands as one of the most memorable examples of the journal’s fearless satire, embodying its ethos of graphic innovation married to uncompromising politics.

Reception, Censorship, and Legacy

At the time, officials decried L’Assiette au Beurre as subversive. Police and magistrates recognized themselves in Vallotton’s caricatures and lobbied for bans or prosecutions. The artist himself faced criticism for encouraging disrespect for authority. Yet the journal’s popularity soared among intellectuals, workers, and liberal circles. In retrospect, Vallotton’s image is celebrated as a milestone in political illustration, prefiguring the advent of modern editorial cartoons. His fusion of avant-garde aesthetics with polemical content influenced later movements—Dada, Surrealism, and the anti-fascist prints of the 1930s. Today, the plate is studied both for its artistry and as a document of early 20th-century dissent, reminding us of art’s capacity to challenge entrenched power.

Conclusion

Félix Vallotton’s “Ah ! bougre de salaud, tu m’as appelé vache !” is a tour de force of political satire and graphic invention. Through its spare composition, biting caption, and stark tonal contrasts, the image exposes the brutality of state authority and the absurdity of its claims to moral superiority. Rooted in the turbulent climate of Third Republic France and the radical mission of L’Assiette au Beurre, Vallotton’s plate transcends its immediate context to become a universal indictment of power’s caprice. Over a century after its publication, its precise lines and indignant humor continue to resonate, reminding us that the graphic arts remain a vital forum for social critique.