Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context and the Emergence of Realism

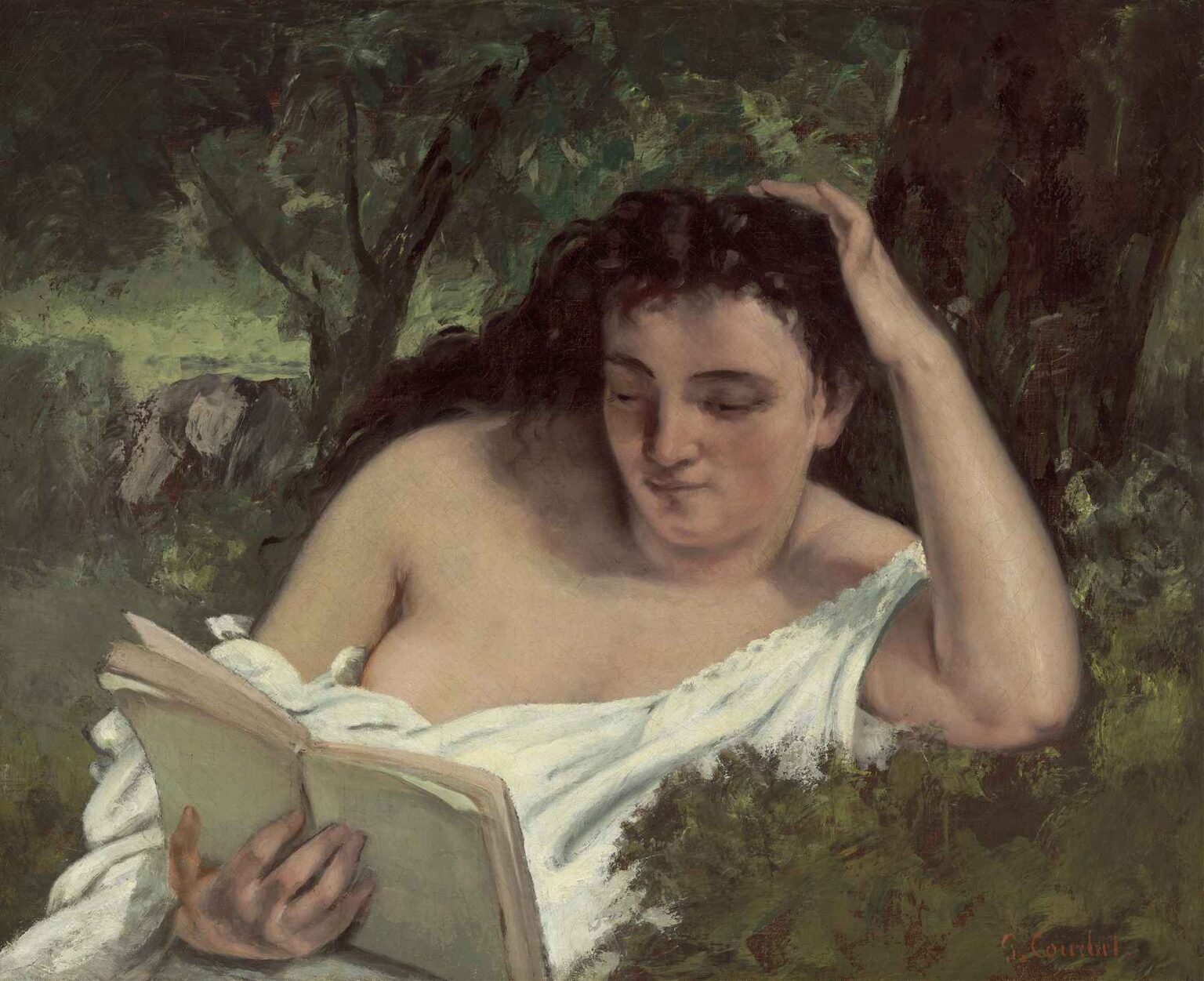

Painted in 1865, A Young Woman Reading (La Liseuse) belongs to a pivotal moment in French art when the academic hierarchy of subject matter and style was being challenged by a new generation of artists. Courbet, a leading figure of the Realist movement, rejected the idealized mythology and Romantic excesses favored by the École des Beaux-Arts and the Paris Salon. Instead, he sought to portray ordinary people and scenes drawn from contemporary life with unvarnished honesty. France in the 1860s was rapidly modernizing under the Second Empire: railroads expanded, Haussmann’s renovation transformed Paris, and the bourgeoisie grew in wealth and influence. In this climate of social change, Courbet’s frank depictions of rural laborers, barroom brawls, and quiet domestic moments spoke directly to the lived experience of his contemporaries. A Young Woman Reading exemplifies this ethos: a humble moment of a woman absorbed in a book, rendered without romantic gloss but with a potent sense of presence and materiality.

Gustave Courbet: Life, Career, and Artistic Philosophy

Born in 1819 in Ornans, a small town in the Franche-Comté region, Gustave Courbet trained briefly in Paris before returning home to develop his style outside the constraints of academic conventions. His early successes with canvases such as The Stone Breakers (1849) and A Burial at Ornans (1849–50) established him as a champion of Realism. Courbet famously stated, “I cannot paint an angel because I have never seen one,” underlining his commitment to painting only what he observed directly. By the mid-1860s, he had become both celebrated and controversial, exhibiting at the Salon of 1850–51 and later organizing independent exhibitions when the official jury rejected his works. Courbet’s studio in Paris became a hub for avant-garde thinkers, writers, and artists who admired his technical skill and his uncompromising insistence on artistic freedom. A Young Woman Reading, created in the midst of these debates, reflects his mature style: loose yet controlled brushwork, tonal harmonies grounded in local color, and a powerful conviction of the reality before him.

Subject Matter and Psychological Insight

At first glance, A Young Woman Reading appears to depict a simple vignette: a young woman in a white dress seated outdoors, immersed in a book. Yet the painting’s emotional resonance lies in the inscrutable expression on her face and the subtle tension of her posture. She leans slightly forward, her left hand raised to tuck a loose strand of hair behind her ear, perhaps a gesture of concentration or self-awareness. Her right hand holds the open book, its pages catching a sliver of light. Courbet offers no clues about the text: is it a novel, a letter, a religious tract? The viewer is left to imagine what might have captured her attention so fully. This ambiguity transforms the scene from mere domestic study to a moment of private interiority, inviting empathetic engagement with the sitter’s inner life. Courbet’s refusal to idealize her features—a faint blemish, soft modeling of flesh, the slightly pensive set of her lips—underscores his commitment to authenticity over prettification.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Courbet constructs the composition using a diagonal thrust that runs from the lower left corner—where the open book protrudes—up through the woman’s torso to the upper right, where the leafy canopy frames her head. This diagonal gives the painting dynamic tension, contrasting with the stillness of her seated pose. The lower half of the canvas is dominated by the white of her dress and the light-brown earth beneath her, while the upper portion recedes into darker greens and browns of foliage and tree trunk. The play of light and shadow not only models three-dimensional form but also guides the viewer’s eye: the brightest area is her chest and the open pages, drawing immediate attention; from there, the gaze follows her arm up to her face and then drifts into the mysterious depths of the forest behind. Courbet has placed her slightly off-center to the left, creating a sense of immediacy as though the viewer has happened upon her in a quiet glade.

Use of Color and Light

The painting’s subdued palette reflects Courbet’s interest in “local color”—the natural hue of objects under ambient light—tempered by his mastery of chiaroscuro. The white dress, rendered in varied warm and cool whites, captures the interplay of sunlight filtering through leaves. Hints of green and ochre in the shadows of the folds suggest reflections from the surrounding vegetation. Her skin tones—faintly warm in the highlights, subtly cool in the shadowed planes—reveal Courbet’s sophisticated layering of glazes and scumbles. The open book’s pages catch a direct shaft of light that illuminates the subject’s engrossment, while the dark areas of the background serve as a foil to her illuminated form. Courbet achieves a harmonious balance between light and dark, color and tonal unity, without resorting to dramatic theatricality: the scene remains naturalistic, anchored in careful observation of how light behaves in an open-air setting.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Courbet’s brushwork in A Young Woman Reading is both vigorous and nuanced. In the foliage, thick impasto and broad strokes convey the rough texture of bark and leaves. The dappled effect of sunlight is achieved through rapid, broken touches of olive-green and yellow ochre. By contrast, the handling of the figure’s flesh and drapery is smoother and more controlled, though still decidedly painterly. The gently carved edges of her arms and shoulders are defined by subtle shifts in value rather than hard outlines. Courbet’s technique involved laying in dark passages first and working toward light, a method that lends the painting a sense of depth and structure. Scratches and cross-hatching in the background, visible close-up, reveal the artist’s process: the initial sketches, the shifting of compositional elements, and the eventual build-up of paint layers that culminate in the unified surface we see today.

Costume, Social Class, and Realist Deliberation

The young woman’s attire—a simple white cotton or linen dress—signals her social position. Unlike the elaborate gowns of aristocratic portraiture, her clothing is modest yet well-made, perhaps marking her as a member of the rising provincial bourgeoisie or a modestly prosperous rural dweller. The looseness of the bodice and the informal arrangement of her hair—worn down rather than in an elaborate updo—underscore the informal, private nature of the scene. Courbet’s choice to depict a figure engaged in reading—a pastime associated with education and leisure—aligns with Realism’s interest in contemporary social realities rather than mythological or historical grandeur. It also subtly celebrates women’s intellectual pursuits at a time when female literacy and access to literature were growing but by no means universal.

The Landscape Setting as Psychological Mirror

Although the painting offers little detail on the broader landscape, the suggestions of lush undergrowth, tree trunks, and a distant sunlit clearing create a self-contained world that mirrors the reader’s inner focus. The natural setting evokes Romantic themes of the forest as a place of retreat and reflection, yet Courbet subjects this motif to realist scrutiny. There is no overt symbolism—no hidden grotto or dramatic storm clouds—but the encircling vegetation provides a protective, almost womb-like space where the woman can immerse herself in the written word. Courbet’s decision to set the scene outdoors rather than in a domestic interior underscores the accessibility of nature as a venue for intellectual and emotional engagement, challenging the rigid boundaries between public and private spheres.

Courbet’s Treatment of Female Subjects

Courbet’s depiction of women is often marked by candor rather than idealization. Whether portraying prostitutes in The Meeting (1854) or bathers in The Bathers (1853), he eschewed conventional notions of feminine beauty in favor of authenticity. A Young Woman Reading continues this approach: the sitter is neither a mythic muse nor a decorative object of desire but a real individual absorbed in a personal activity. Her expression is not inviting or coquettish; it is one of concentration. Courbet’s rendering refuses to objectify her solely as a female figure and instead presents her as an active subject—an agent of her own intellectual adventure. This treatment aligns with the democratic ideals of Realism, which sought to elevate ordinary life subjects to the dignity of high art.

Interpretive Readings: Literacy, Leisure, and Gender

At its simplest, the painting celebrates the joy of reading. The open book’s prominence suggests that knowledge and imagination can transport the individual beyond immediate surroundings. Yet the gendered dimension adds complexity: a solitary woman reading in isolation—removed from domestic chores or social functions—hints at progressive notions of female autonomy. In 1860s France, debates regarding women’s education and social roles were intensifying. Courbet’s depiction may reflect sympathy for broader access to intellectual pursuits, even as it stops short of overt political commentary. The absence of male presence emphasizes a private conversation between reader and text, unmediated by patriarchal oversight. Modern viewers might therefore read the painting as an early feminist statement, celebrating a woman’s right to leisure, education, and inner life.

Reception, Criticism, and Legacy

When first exhibited, A Young Woman Reading garnered modest attention compared to Courbet’s larger historical and rural scenes. Critics praised its technical accomplishment but were ambivalent about its seemingly trivial subject. Over time, however, the painting has been reevaluated as a key work in Courbet’s portrait oeuvre. Its honest representation of female interiority anticipates later Realist and Impressionist explorations of private moments—Manet’s reading women, Renoir’s domestic scenes, Morisot’s garden portraits. Art historians now view it as a bridge between Courbet’s early confrontational Realism and his later more intimate works. The painting’s influence extends to 20th-century artists interested in the quiet power of everyday gestures and the psychological depth found in ordinary acts.

Provenance, Conservation, and Current Location

A Young Woman Reading passed through private collections in France before entering the holdings of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it remains a prized example of mid-19th-century portraiture. Conservation efforts have focused on stabilizing the darkened layers of varnish that had muted the luminosity of the whites and flesh tones. Recent cleaning revealed the full range of Courbet’s tonal subtleties, restoring the brilliance of the sunlit dress and the nuanced modeling of the sitter’s skin. High-resolution imaging has also allowed scholars to study Courbet’s underdrawing and technical revisions, illuminating his working methods and the adjustments he made to achieve the final composition.

Conclusion

A Young Woman Reading stands as one of Gustave Courbet’s most compelling portraits of private life. Through its unembellished subject matter, masterful handling of light and paint, and subtle interplay of psychological insight and social commentary, the painting embodies the Realist conviction that everyday scenes are worthy of monumental treatment. Courbet’s refusal to idealize his sitter and his celebration of female intellectuality resonate across generations, inspiring new interpretations in the contexts of modern feminist critique and the enduring fascination with reading as an act of personal transformation. Over 150 years after its creation, A Young Woman Reading continues to captivate audiences, reminding us that the most profound moments often unfold in quiet contemplation beneath the dappled sunlight of a secluded glade.