Image source: artvee.com

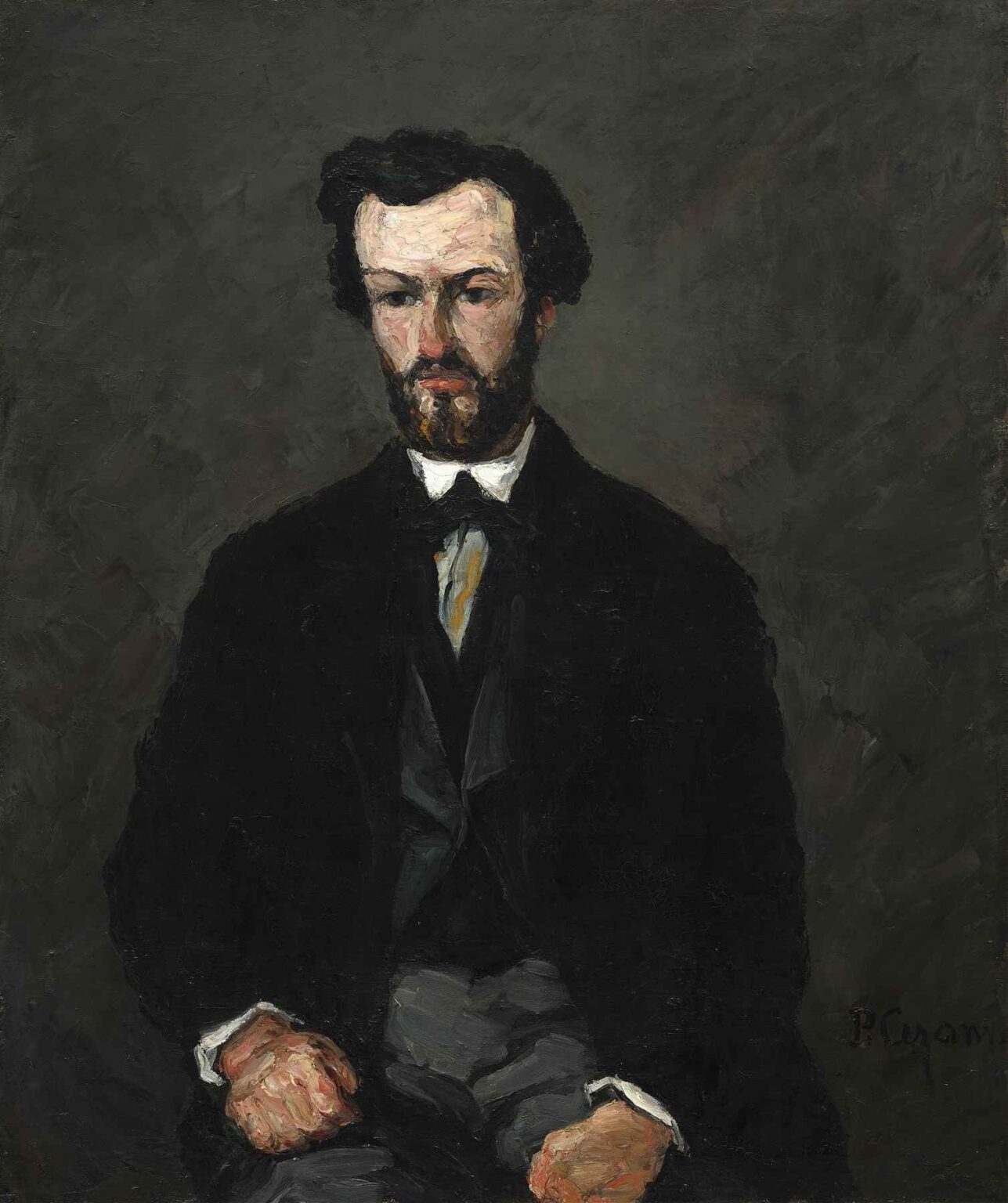

Paul Cézanne’s Antony Valabrègue, painted in 1866, stands as a significant early work in the oeuvre of the French Post-Impressionist master. Though the painting predates Cézanne’s mature style—famed for its structural brushwork and the analytical approach to form that would influence Cubism—it is nonetheless a remarkable statement of psychological depth and radical painterly instinct. Unconventional in composition, coloring, and technique, this brooding portrait marks Cézanne’s first foray into capturing the interiority of a close companion through an expressive, rather than purely representational, visual language.

The subject of this portrait, Antony Valabrègue, was a poet, art critic, and close friend of Cézanne during his early years in Aix-en-Provence. Their bond was rooted in mutual artistic aspiration and youthful rebellion against the academic conventions of the mid-19th century. While Valabrègue would later contribute to the art world as a supporter of modern painters, Cézanne immortalized him with brush in hand, rendering his figure not as a polished likeness but as a dense, introspective presence.

This analysis will explore the context, compositional structure, technical approach, psychological atmosphere, and long-term importance of Antony Valabrègue in Cézanne’s development—and how this dark, powerful painting anticipated many elements of modern portraiture.

Historical and Biographical Context

In 1866, Cézanne was 27 years old, caught in the struggle between academic rejection and avant-garde independence. Though he had studied briefly at the Académie Suisse in Paris, he never fully adopted academic norms. Instead, he painted with an intensity that verged on obsession—layering pigment thickly, often working and reworking canvases, and testing the limits of paint to express raw emotion.

This portrait was painted during Cézanne’s so-called “dark period,” characterized by murky color palettes, turbulent brushwork, and subject matter that veered toward the melancholic and introspective. His aesthetic at the time was influenced by Romanticism, particularly Delacroix, and by the psychological depth found in works by Courbet. Yet Cézanne was also developing something new—an approach to the portrait that sought to extract not just physical appearance but a deeper essence.

Antony Valabrègue, a writer and art critic who would later pen defenses of Cézanne, was a friend from Aix who shared the painter’s alienation from Parisian society. Their intellectual and creative exchanges were foundational in Cézanne’s early development. Immortalizing Valabrègue in a portrait was both an artistic and emotional gesture—a tribute, a challenge, and a kind of manifesto.

Composition and Structure

The composition of Antony Valabrègue is stark and minimal. The figure is centered but slightly slouched, his hands resting heavily in his lap. There is no elaborate setting, no background detail, no ornamental device to distract the viewer. Instead, the entire visual weight rests on the subject’s form and the psychological tension it conveys.

The head is framed roughly at the vertical midpoint of the canvas, allowing the torso and hands to take up significant space. This vertical emphasis contrasts with the horizontal rigidity of the seated pose, creating a compressed energy. Valabrègue’s gaze is downward and indirect, evading confrontation, while the tight composition presses in around him, emphasizing a sense of isolation or introversion.

Cézanne does not romanticize his friend. Instead, the figure appears heavy, slightly rough, his features set in a grim or contemplative expression. The hands, disproportionately large and rendered with angular strokes, draw attention to their restive position—neither at ease nor active. These elements heighten the sense of psychological unease.

Use of Color: A Palette of Psychological Depth

One of the most immediately striking aspects of Antony Valabrègue is its palette. The dominant tones are dark, muddy, and earthbound—black, umber, olive green, and muted gray, punctuated only by the pale flesh of the hands and face. Even those areas, however, are tinged with gray and red, creating a sense of internal tension.

Cézanne’s dark palette during this period has often been interpreted as an expression of emotional turmoil or artistic defiance. Rather than use color to flatter or illuminate, he employs it to create mood. The background is a turbulent sea of deep gray and brown, applied with uneven strokes that barely differentiate it from the figure itself. The subject seems almost embedded in shadow.

Yet within this murkiness, there are glimmers of subtle modulation. The light catches Valabrègue’s forehead, the bridge of his nose, the crest of his hands. These areas are not brightly highlighted but gently lifted from the gloom, giving the viewer just enough visibility to construct the facial geometry. The result is a portrait that feels sculpted from shadow, built up from an inner logic rather than illuminated from without.

Brushwork and Materiality

Cézanne’s brushwork in Antony Valabrègue is thick, visible, and unapologetically material. This is not the polished finish of Salon portraiture. The surface is active, even raw, with paint applied in bold, rough patches that resist linear clarity. The face is shaped by short, overlapping strokes; the hair is an entangled field of black and gray; and the suit jacket is a mass of dark, undifferentiated paint.

This vigorous handling of paint aligns Cézanne with the Realist tradition, particularly Gustave Courbet. But while Courbet’s Realism had a social dimension, Cézanne’s is more psychological. He uses the instability of the paint surface to mirror the internal state of the subject—and perhaps his own internal unrest as a painter.

Importantly, the roughness of execution is not accidental. It reflects a deliberate rejection of academic ideals of polish and perfection. Cézanne was in search of a new visual language—one that prioritized substance over appearance, depth over prettiness. In Antony Valabrègue, we see the early manifestation of this radical philosophy.

Psychological Interpretation

The emotional tenor of the portrait is subdued, almost oppressive. Valabrègue’s expression is withdrawn, his eyes hollowed, his lips sealed. There is no trace of idealization. The overall effect is one of solemnity, introspection, and existential gravity.

Some scholars have suggested that the portrait reveals as much about Cézanne as it does about his sitter. The closed-off posture, the heavy atmosphere, the indistinct background—all hint at the painter’s own sense of alienation and uncertainty during this formative period. Valabrègue becomes not only a portrait subject but a stand-in for the artist’s search for identity.

Despite its somberness, there is a quiet dignity in the painting. The sitter is not diminished, merely rendered with brutal honesty. He is solid, present, and real. The very lack of embellishment becomes a statement of truth—a philosophical stance as much as an aesthetic one.

Significance in Cézanne’s Career

Antony Valabrègue is often cited as one of Cézanne’s most important early portraits. While it predates his signature style of faceted brushwork and structural spatial construction, it lays the psychological and material groundwork for what was to come. This painting is Cézanne in search of himself: shedding the artifice of academic training, pushing against the boundaries of convention, and groping toward a new mode of artistic truth.

This portrait is also significant because it encapsulates Cézanne’s shift from Romanticism to modernism. The brooding tone, while emotionally intense, is conveyed through formal means—composition, color, brushwork—not through allegory or idealization. In that sense, Antony Valabrègue anticipates the core concerns of modern portraiture: interiority, abstraction, and the exploration of paint as a language in itself.

Reception and Legacy

In Cézanne’s lifetime, works like Antony Valabrègue were largely misunderstood or ignored. The darkness of his palette, the apparent awkwardness of his forms, and the refusal to flatter did not sit well with the Parisian art establishment. Yet these very qualities would later be praised by modernist critics and artists as the seeds of a new vision.

Today, the painting is housed in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and is widely regarded as a masterpiece of psychological portraiture. It is studied not only for its biographical interest but for its aesthetic power and historical significance.

Modern viewers recognize in Antony Valabrègue the beginnings of a revolution. Cézanne was not merely painting what he saw—he was constructing a new visual truth, one brushstroke at a time.

Conclusion: A Portrait of Friendship, Turmoil, and Vision

Paul Cézanne’s Antony Valabrègue is a painting of quiet intensity and lasting influence. Painted at a time when the artist was still struggling to define his path, it represents a pivotal moment in the evolution of modern art. With its somber palette, expressive brushwork, and psychological gravity, the portrait confronts the viewer with more than a likeness—it offers an encounter with another human being, rendered through the lens of artistic risk and emotional depth.

In this image of a seated poet, we see the earliest expression of Cézanne’s lifelong commitment to seeing beyond surfaces, to rendering the truth of form, and to transforming paint into presence. Antony Valabrègue is not a perfect portrait. It is, however, a profoundly honest one—and in that honesty lies its enduring power.