Image source: artvee.com

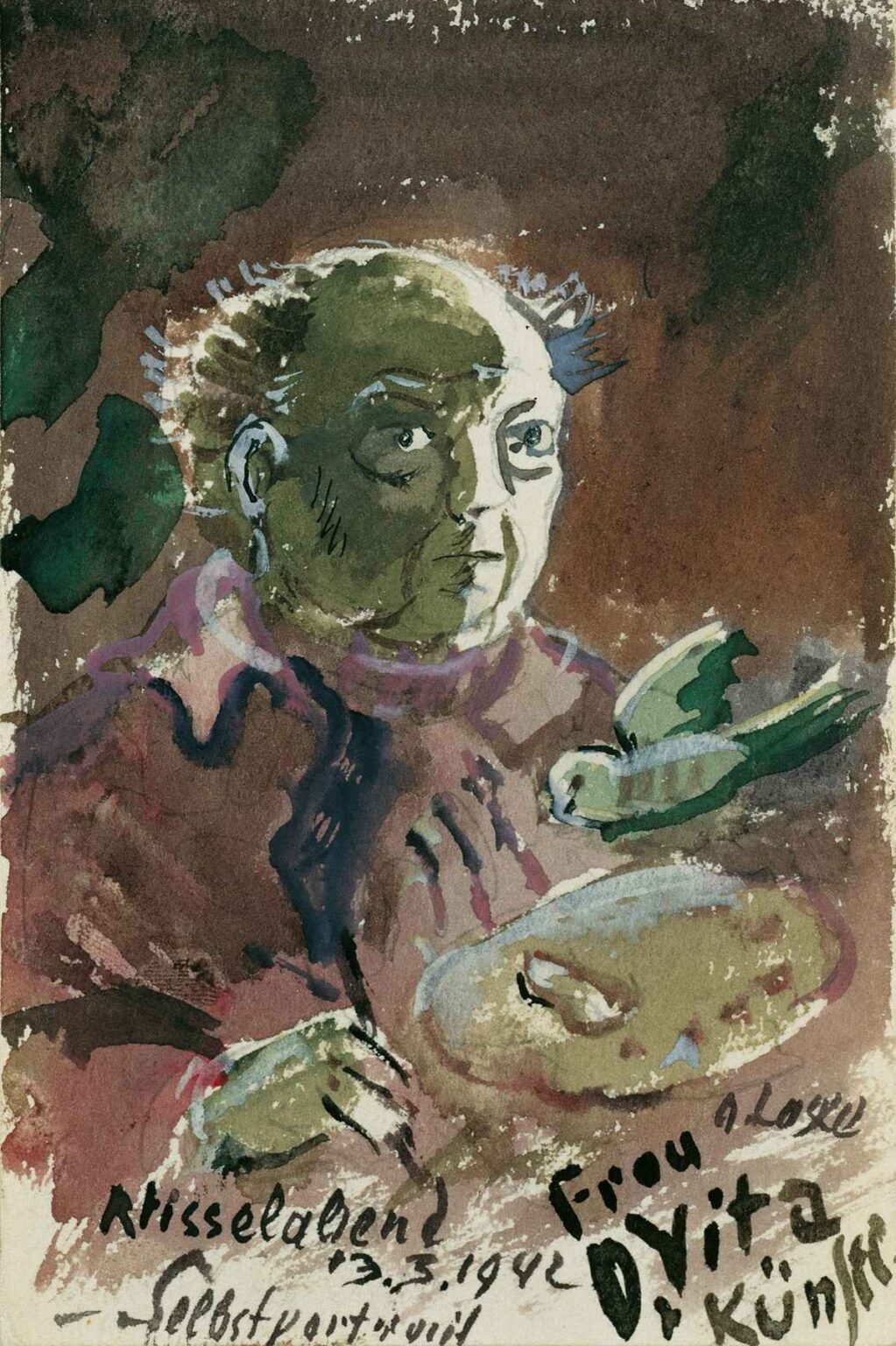

Oskar Laske’s Self-Portrait (1942) stands as a compelling and enigmatic work of mid-20th-century Austrian art. Painted during a time of immense personal and global turmoil, the work reveals a deeply introspective and symbolic depiction of the artist, rendered in a unique fusion of Expressionist and Naïve styles. Though relatively small in format, Laske’s Self-Portrait holds immense psychological and historical weight, combining gestural brushwork, surreal forms, and coded text to present an identity shaped by creativity, conflict, and cultural dislocation.

In this analysis, we explore the visual composition, contextual background, stylistic hallmarks, symbolic meanings, and emotional resonance of Self-Portrait by Oskar Laske. The painting is not only a personal meditation on art and identity but also a historical artifact of Austria’s artistic resistance in the face of fascism, war, and personal loss.

About the Artist: Oskar Laske (1874–1951)

Oskar Laske was an Austrian painter and architect best known for his allegorical, fantastical, and often densely populated compositions. A member of the Vienna Secession and the Hagenbund, Laske developed a distinct artistic voice influenced by Symbolism, Expressionism, and Naïve Art. His works often merged architectural precision with whimsical fantasy, echoing the dreamlike visual storytelling of Hieronymus Bosch or James Ensor.

By the time Laske painted Self-Portrait in 1942, he was nearly seventy years old and living through the ravages of World War II. Austria had been annexed by Nazi Germany, and many of Laske’s artistic colleagues had fled, been persecuted, or forced into silence. Against this backdrop of political repression and existential uncertainty, Self-Portrait emerges as both a reflection of individual resilience and a coded statement of inner truth.

Visual Composition and Medium

Laske’s Self-Portrait is a watercolor and gouache painting executed on paper. The image is framed tightly, focusing on the upper half of the artist’s body as he confronts the viewer. The figure is surrounded by murky, abstract swathes of brown, green, and black, with no clear horizon or architectural space. The background evokes a psychological rather than physical setting, suggesting a world turned inward.

At the center is the artist himself, with exaggerated, almost grotesque features: high-arching brows, bulbous cheeks, and penetrating eyes. His face is rendered in expressive patches of dark green and pink, lending a spectral, otherworldly aura to the figure. The hair stands wild and electrified, suggesting nervous energy or creative frenzy. Laske holds a palette in his left hand and a green bird perches on the edge—an unusual but symbolic companion.

Beneath the figure, scrawled in an urgent and expressive hand, are inscriptions that identify the place (Klosterneuburg), the date (3.3.1942), and the nature of the work: Selbstporträt (self-portrait). The artist’s name, “Oskar Laske,” appears in stylized letters along with “Für Dyta,” presumably referring to his daughter or a loved one. The presence of both image and text reveals Laske’s layered approach to self-representation, blending visual metaphor with personal annotation.

Expressionist Aesthetics and Naïve Intensity

Stylistically, Laske’s Self-Portrait belongs to the Expressionist tradition, yet it also bears qualities associated with Outsider and Naïve Art. Expressionism, as a movement, sought to depict the inner emotions and subjective realities of the artist, often through distortion, exaggeration, and heightened color contrasts. Laske employs these techniques to unsettling effect—his own visage appears partly masked, with uneven lighting and misshapen features that hint at psychological fragmentation.

At the same time, the work’s childlike application of watercolor, the intentionally skewed anatomy, and the inclusion of fantastical elements (like the bird) suggest a deliberate embrace of Naïve Art’s directness and spontaneity. This fusion of aesthetic modes enhances the authenticity of the self-portrait. Laske does not present a heroic or idealized version of himself, but one that is vulnerable, aging, and embedded in a dreamlike state of flux.

The lack of spatial realism and the raw, almost primitive handling of form and line lend the painting an intense immediacy. The viewer is not looking at a staged portrait but witnessing a deeply felt act of self-exploration—more journal entry than formal declaration.

The Bird and the Palette: Symbols of Creative Duality

Two key elements in the painting demand symbolic interpretation: the green bird and the artist’s palette. Birds in art have long symbolized freedom, the soul, and transcendence, while green birds in particular may suggest renewal, fertility, or spiritual vision. In the context of Laske’s portrait, the bird may serve as a surrogate for the artist’s imagination—perched quietly, watching, ready to take flight even as the world around him darkens.

The bird also introduces a note of whimsy and innocence to an otherwise brooding image. It is a reminder that creativity endures, that the act of painting is itself a dialogue between instinct and technique, the intuitive and the crafted.

The palette, meanwhile, functions as a literal and figurative tool. In holding it, Laske identifies himself first and foremost as a creator. The palette is dappled with colors, suggesting ongoing artistic labor and vitality despite the grim wartime context. It is his shield and his weapon, his source of truth and survival.

Together, the palette and bird represent a dual force within the artist: the grounded labor of his hands and the soaring vision of his mind. These symbols humanize the figure and assert his commitment to the role of the artist as a visionary, even in solitude and crisis.

Color and Emotional Atmosphere

The color scheme of Self-Portrait is earthy, muted, and bruised. Browns, olive greens, muddy reds, and sooty blacks dominate the composition. These are not the colors of spring or sunlight—they are the hues of decay, soil, shadow, and conflict. The palette evokes a world reduced to ashes and ambiguity, a psychological landscape colored by uncertainty and isolation.

The lighting in the portrait is uneven, with some areas washed out and others steeped in shadow. This chiaroscuro effect adds to the emotional dissonance of the piece: the artist appears both illuminated and haunted. The halo-like aura around the head, composed of pale washes and erratic strokes, adds a layer of mysticism, perhaps referencing the archetype of the artist as prophet or martyr.

The emotional register of the painting is complex. There is melancholy and fatigue, but also resilience. The wide, intense eyes suggest alertness and awareness. The brushwork, while loose and expressive, never collapses into chaos—it maintains structure and intention. Even in abstraction, Laske communicates presence and willpower.

Text and Identity: The Role of Inscription

What sets Laske’s Self-Portrait apart from many self-representations of the era is its use of text. The handwritten notes at the bottom of the painting give it the feel of a signed letter, a personal communiqué rather than a gallery-ready artifact. The location (“Klosterneuburg”) and date (“3.3.1942”) situate the work in both geographic and historical specificity.

The mention of “Für Dyta” makes the painting not only an act of self-definition but also one of communication—intended for a loved one. It suggests intimacy and urgency, perhaps even a form of resistance against the silencing effects of war. In this sense, the painting becomes a testament: I am here, I remember, I continue.

The handwriting itself is energetic and unrefined, mirroring the spontaneity of the image. It collapses the distance between word and image, artist and viewer, self and other. Laske is not simply depicting himself; he is speaking, inscribing his presence into the paper with ink and pigment alike.

Historical Context: 1942 and the Shadow of War

The painting’s date—1942—is critical. By this point in World War II, Austria had been annexed into Nazi Germany for four years. The art world, once thriving with innovation and experimentation, was under heavy censorship. Many artists were declared “degenerate,” and their work was banned or destroyed.

Although Laske was not Jewish, he belonged to a liberal, cosmopolitan intelligentsia that was deeply at odds with fascist ideology. His insistence on fantasy, individuality, and expressive freedom ran counter to the aesthetic mandates of the Nazi regime. To create and sign a self-portrait in this style at this time was, in itself, an act of defiance.

Self-Portrait can thus be read as a private protest. In the face of erasure and conformity, Laske asserts his unique voice—fractured but unmistakably alive. The portrait becomes a quiet, coded resistance to authoritarian culture: a man alone with his art, refusing to vanish.

Legacy and Interpretation

Oskar Laske’s Self-Portrait remains a vital example of how the personal and political intersect in visual art. Though small in size, the work encapsulates a lifetime of experience and a moment of existential reflection. It is at once haunting and hopeful, fragmented yet coherent.

In terms of art history, the painting bridges early 20th-century Symbolism with the postwar rise of Outsider Art and psychological abstraction. It stands apart from the clean, monumental self-portraits of official portraiture and aligns more closely with the confessional works of Edvard Munch, Egon Schiele, or Käthe Kollwitz.

For contemporary viewers, Laske’s portrait offers a timeless meditation on aging, creativity, and the human spirit under pressure. It reminds us that art, at its most honest, is not about perfection but presence—the act of seeing oneself clearly, and sharing that vision, however raw, with the world.