Image source: artvee.com

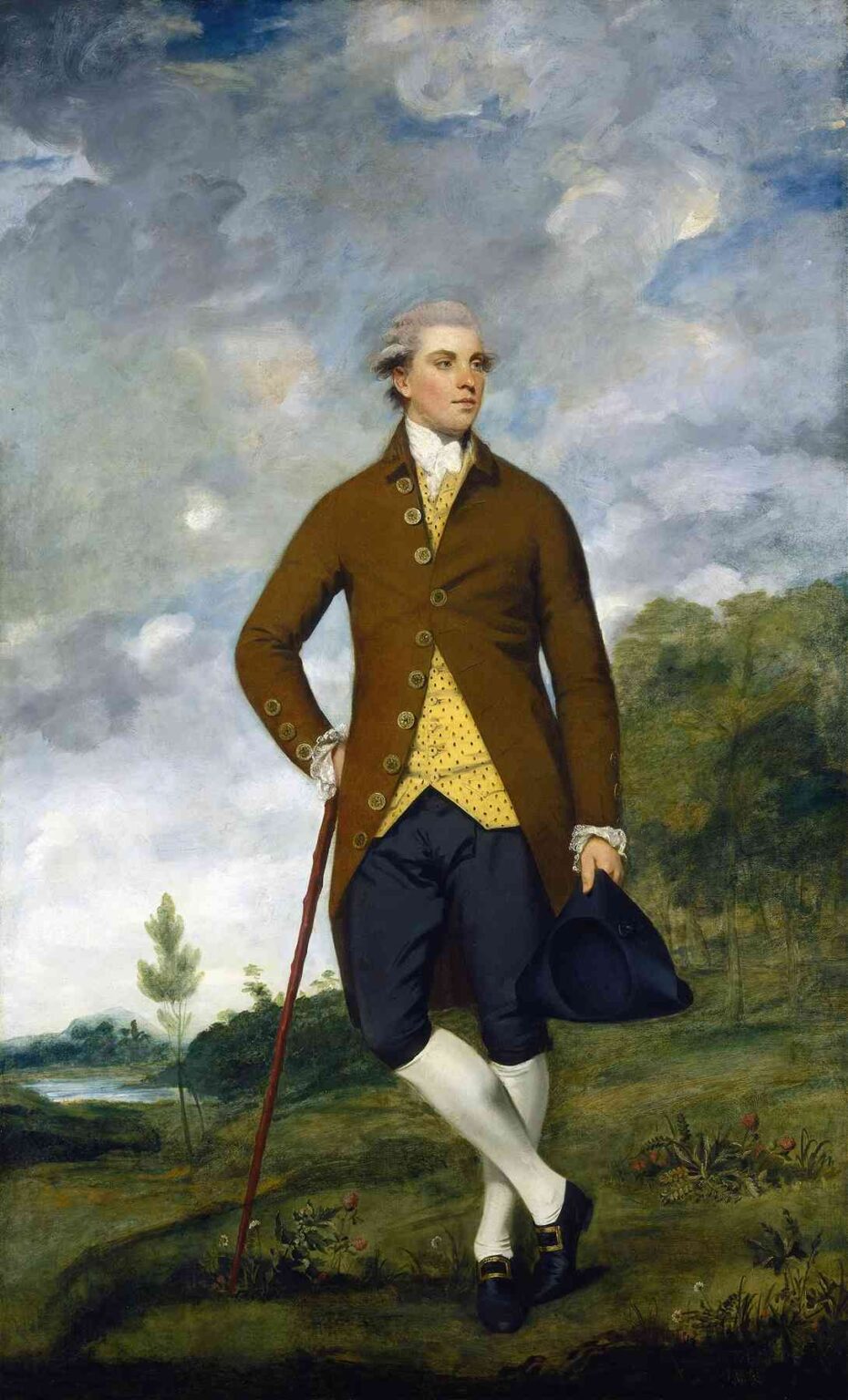

Sir Joshua Reynolds, one of the most influential British portraitists of the 18th century, captured the ideals of aristocratic elegance, masculine refinement, and Enlightenment poise in his celebrated 1770s portrait John Musters. As a figure central to the social and sporting circles of Georgian England, Musters appears here in a striking pose set against an expansive natural landscape. With every detail—from the ruffled cuffs and polished cane to the carefully composed clouds—Reynolds reinforces both the social authority and cultivated sensibility of his subject.

This analysis delves into the historical context, visual composition, symbolism, and artistic innovation of John Musters. Through Reynolds’s brushwork and conceptual framework, the painting not only immortalizes an individual but offers a visual treatise on identity, masculinity, and status in late 18th-century Britain.

Historical Context: Reynolds and the Rise of Grand Manner Portraiture

By the time John Musters was painted, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) had cemented his position as England’s foremost portrait painter and was serving as the first president of the Royal Academy. Deeply inspired by the Old Masters—especially Raphael, Rembrandt, and Titian—Reynolds developed what came to be known as “Grand Manner” portraiture. This style combined naturalistic likenesses with idealized settings and poses derived from classical sculpture and Renaissance painting, designed to elevate the sitter’s status beyond mere representation.

John Musters (1753–1827), the subject of the portrait, was a wealthy landowner, sportsman, and figure of high society, later nicknamed “the handsomest man in England.” He epitomized the Georgian gentleman: educated, leisured, and attuned to taste, fashion, and land stewardship. In depicting Musters, Reynolds not only painted a fashionable young man but also a cultural ideal.

The portrait was likely commissioned to commemorate Musters’s entrance into adulthood or inheritance—a common practice among the landed gentry and aristocracy. It also functioned as a public statement of social standing, displayed prominently in the family estate or local salon.

Composition and Pose: The Embodiment of Elegance

One of the most striking features of the painting is the poised, almost theatrical stance of the sitter. John Musters stands with one leg crossed over the other, a red walking cane in his left hand and a tricorn hat held delicately in his right. His torso twists subtly toward the viewer, while his head is turned in three-quarter profile, gazing confidently into the distance.

This contrapposto pose, derived from classical statuary, conveys both grace and ease—attributes essential to the ideal of the English gentleman. The deliberate yet natural stance balances the energetic upward sweep of the cane with the grounded weight of his crossed legs, creating an elegant visual harmony.

Musters’s clothing further reinforces his genteel identity. He wears a rich, golden-yellow waistcoat speckled with pattern beneath a rust-colored coat, deep navy breeches, and ivory stockings. The abundance of fine lace at his cuffs and cravat, along with the buckle shoes, situates him within the elite strata of Georgian fashion. These sartorial elements are not mere accessories but symbols of refinement, discipline, and prosperity.

The Landscape Setting: Nature as Virtue and Power

Unlike the tightly framed bust portraits of earlier centuries, John Musters places the sitter in a vast, idealized landscape. The background consists of rolling meadows, distant trees, a river, and a cloudy sky painted in soft, swirling strokes. This pastoral environment is not incidental. It reinforces a key Enlightenment-era ideal: the landowning gentleman as moral steward of nature and civil society.

The natural world, in this context, becomes a mirror of the subject’s inner harmony and rational control. Musters is shown not merely enjoying the landscape, but commanding it. His grounded pose and elevated gaze suggest dominion and intellect, echoing the Enlightenment belief in man’s ability to shape the world through reason.

Furthermore, the wild but temperate quality of the landscape mirrors the balance between strength and sensitivity that Reynolds aimed to convey. The patches of flowers, the meandering path, and the soft distant hills imply cultivated wilderness—a metaphor for Musters himself: cultured, controlled, yet close to nature.

Brushwork and Lighting: A Fusion of Precision and Atmosphere

Reynolds’s brushwork in John Musters is a tour de force of late 18th-century portraiture. The textures of fabric, flesh, and flora are rendered with subtle differentiation. The crisp edges of Musters’s coat and waistcoat contrast with the softer, more impressionistic treatment of the clouds and grasses, creating a dynamic interplay between form and environment.

Reynolds often experimented with layering glazes and varnishes to achieve luminosity, and this painting exemplifies his pursuit of radiant skin tones and shimmering highlights. The face of Musters is illuminated with a soft, diffuse light that sculpts the features without harsh contrast, imbuing the sitter with youthful vigor and moral clarity.

His powdered wig, delicately brushed in silvery gray, reflects contemporary fashion while also serving to highlight the fairness and symmetry of his features. The overall lighting effect reinforces a sense of idealized realism—convincing, yet elevated.

Symbolism and Character Construction

Beyond its surface beauty, John Musters is rich with symbolic resonance. The portrait constructs a carefully coded vision of masculine virtue, elegance, and authority:

The cane suggests mobility, control, and social standing. In the 18th century, walking sticks were often markers of rank and elegance, serving both functional and decorative purposes.

The hat held at his side signals courtesy and restraint. By not wearing it, Musters displays openness and engagement, rather than aloofness.

The landscape represents estate ownership and the pastoral ideal—key values of the landed gentry.

His posture blends alertness with ease, suggesting both readiness and composure, vital traits for a public figure in polite society.

These elements coalesce to portray not only an individual but a social role—the gentleman as a symbol of rational order, cultural refinement, and national stability.

Gender and Performance: Constructing the Ideal Man

One of the often-overlooked dimensions of Grand Manner portraiture is its performative nature. While today we might read this painting as a sincere likeness, it also functions as a staged performance of elite masculinity. Reynolds was acutely aware of the visual vocabulary needed to construct identity, especially among the upper classes.

Musters’s portrait walks a delicate line between natural charisma and cultivated artifice. Every detail, from the lace cuffs to the upright gait, is part of a visual script that communicates class, gender, and moral character. The painting is thus as much about how Musters should be seen as how he truly was.

In this sense, Reynolds’s work anticipates the modern idea of portraiture as branding—a way of curating personal image and social identity.

Legacy and Reception

The portrait of John Musters remains one of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s most admired examples of Grand Manner portraiture. It has been praised not only for its aesthetic sophistication but for its embodiment of 18th-century ideals. Today, the painting resides in collections that celebrate British heritage, and it is frequently cited in scholarly texts on portraiture, masculinity, and Enlightenment culture.

As a historical document, the painting offers invaluable insight into how art functioned in aristocratic society—not merely as decoration, but as a tool of social continuity and self-representation. It helped shape the visual codes of Georgian identity and continues to inform how we understand the aesthetics of status and character.

Moreover, John Musters serves as a benchmark for later developments in portraiture. Romantic painters such as Thomas Lawrence and even early photographers would borrow elements from Reynolds’s formula of drama, landscape, and idealized poise.

Conclusion: Timeless Elegance in Painted Form

John Musters by Sir Joshua Reynolds is more than a portrait—it is a visual manifesto of 18th-century refinement. Through masterful composition, symbolic detail, and luminous brushwork, Reynolds elevates his sitter into an archetype of the English gentleman. The painting reflects not only Musters’s personal charm and station but also the broader ideals of Enlightenment culture: rational order, moral character, and harmonious coexistence with nature.

As an artifact of its time, the portrait reveals how art functioned as both social instrument and personal expression. As a work of enduring beauty, it continues to captivate modern viewers with its balance of elegance, symbolism, and human warmth.

In Reynolds’s hands, a portrait becomes a stage upon which identity, virtue, and aspiration are eternally performed. John Musters stands as a brilliant example of this artful synthesis, its charm undiminished by the passage of centuries.