Image source: artvee.com

Juan Gris’s Abstraction (1915) is a quintessential example of Synthetic Cubism—a movement that sought to reconfigure the visual language of painting through fragmentation, reconstruction, and a radical engagement with form and color. As one of the key figures of the Cubist movement, Gris developed a distinct voice within the avant-garde, characterized by clarity, precision, and poetic structure. This particular painting, created during a pivotal moment in Gris’s career, reveals his mastery of spatial composition and his pioneering approach to abstraction.

In this in-depth analysis, we will explore the formal qualities, conceptual depth, historical context, and artistic innovations that define Abstraction. This 1915 work encapsulates Gris’s commitment to order and harmony, providing insight into both the development of modernist aesthetics and the painter’s singular contribution to Cubism.

Juan Gris and the Evolution of Cubism

Juan Gris, born José Victoriano González-Pérez in Madrid in 1887, moved to Paris in 1906 and quickly became immersed in the artistic circles that defined the early 20th-century avant-garde. Although Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque had initiated Cubism around 1907–1908, Gris brought a distinct sensibility to the movement. Whereas Picasso and Braque often emphasized muted palettes and analytical deconstruction, Gris gravitated toward vivid color, structured compositions, and a synthetic approach that reassembled fragmented forms into cohesive wholes.

By 1915, when Abstraction was painted, Cubism had entered its Synthetic phase. This shift meant that artists were no longer just analyzing objects by breaking them down into planes and facets; they were also reconstructing those objects in new, imaginative ways using vibrant shapes, color juxtapositions, and sometimes collaged materials. Gris, more than any of his contemporaries, championed this compositional synthesis.

Visual Composition: Order Through Fragmentation

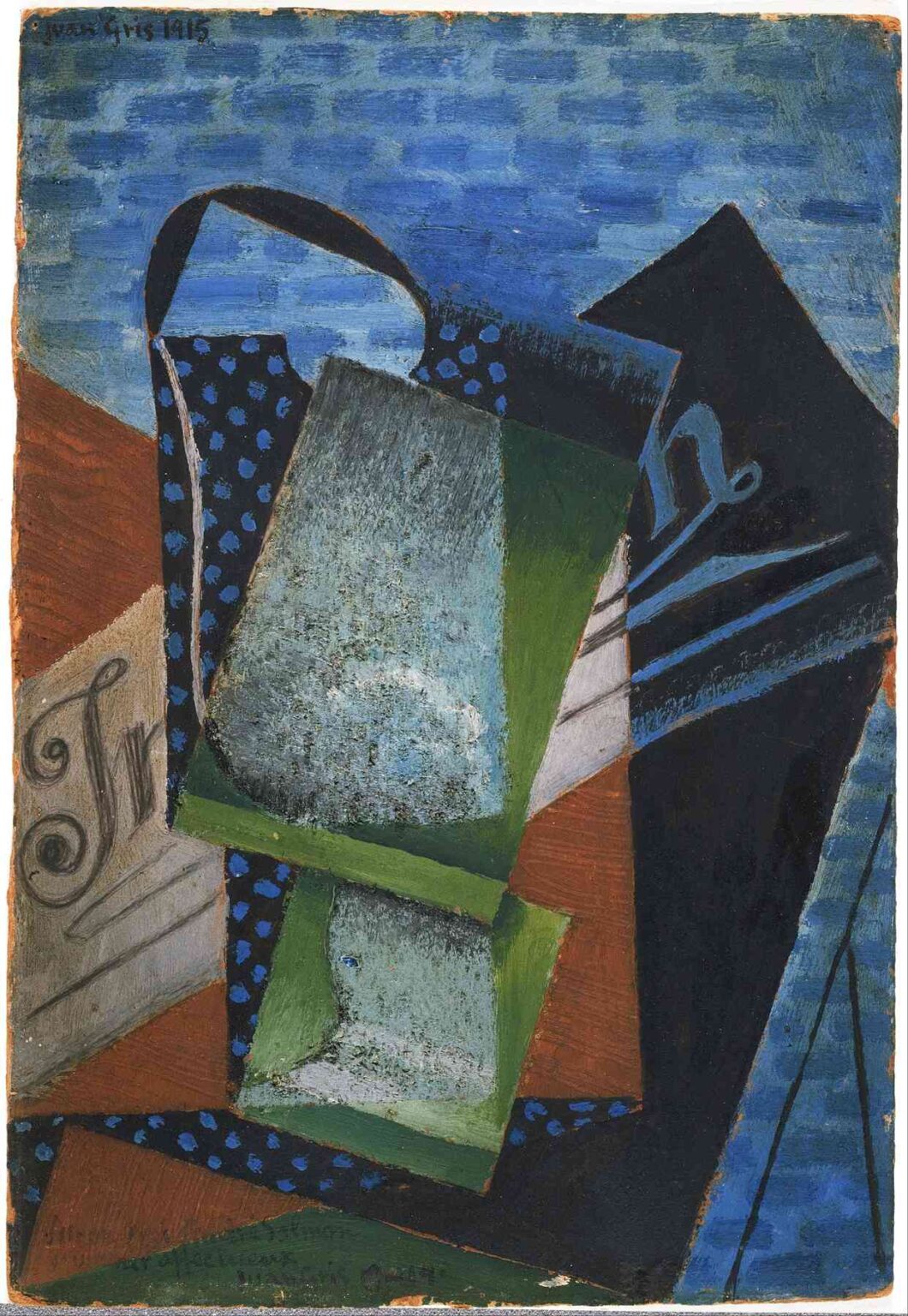

At first glance, Abstraction may seem chaotic or nonrepresentational, but a closer look reveals an intricately balanced arrangement of shapes, textures, and colors. Dominated by rectilinear and curvilinear forms, the composition presents a flattened space in which multiple planes overlap and interlock. One can discern the ghostly outlines of a pitcher or glass, fragments of printed text, and geometric patterns—familiar elements from Cubist still lifes.

The painting’s structure is vertically oriented, and the central focus appears to be a greenish, faceted form resembling a vessel or glass, tilted and layered against other shapes. This central object anchors the composition, while the surrounding forms—suggesting folded paper, drapery, or printed labels—create a sense of rhythm and complexity.

Gris’s approach to abstraction is not arbitrary. Each shape is deliberately placed to establish harmony. The result is a visual architecture, one in which space is not illusionistic but constructed—a conceptual reality rather than an observational one.

The Role of Color: Expressive Geometry

Color in Abstraction is more than a visual embellishment; it serves as a compositional tool. The palette consists primarily of cool blues and greens contrasted with warmer reds and browns. These color fields are applied in flat, opaque layers that reinforce the painting’s sense of surface and structure.

One of the most striking elements is the background: a textured, blue pattern resembling brickwork or woven fabric. This creates a subtle grid that provides order without overwhelming the foreground elements. The speckled areas of blue polka dots—often found in Gris’s works—introduce a playful variation in pattern and texture, suggesting materials like fabric or wallpaper.

The contrast between matte and reflective surfaces also plays a crucial role. Gris often simulated different materials using oil paint—woodgrain, newsprint, metal, and glass—all rendered with graphic clarity. In Abstraction, the interplay between painted illusion and real texture deepens the viewer’s engagement with the painting.

Textual Elements and the Suggestion of Reality

A hallmark of Synthetic Cubism is the integration of text into the pictorial space. In Abstraction, we see fragments of letters and cursive script—perhaps the beginnings of words like “In” or “Fr”—floating among the shapes. These textual elements hint at reality: a newspaper, a wine label, or a café sign. Their presence grounds the abstraction in the sensory world, even as the forms remain fractured.

Gris’s use of typography suggests a hybrid of painting and collage. While Picasso and Braque often included real pieces of newsprint or wallpaper in their collages, Gris mimicked these textures and texts through meticulous painting. This technique creates a dual layer of perception: we recognize the familiar, yet we are always aware that we are looking at an artifice.

This tension between the real and the abstract is central to Abstraction. The viewer is invited to decode the image, to reconstruct the disassembled objects, and to appreciate the painting not just for what it represents, but for how it has been constructed.

Materiality and Technique

Although Gris is sometimes overshadowed by Picasso and Braque in discussions of Cubism, his technical virtuosity is undeniable. Abstraction is rendered with a precision that belies its complexity. The surface of the painting is finely worked, with crisp edges, subtle shading, and deliberate texture.

Gris favored oil on canvas but often painted on wood panel, as he did in Abstraction. The hardness of the wood allowed for greater control over detail and surface finish. His brushwork is deliberate and controlled, lacking the gestural energy of later abstract painters. Instead, Gris achieves dynamism through composition and color interaction.

It is this meticulous technique that gives Abstraction its architectural solidity. The painting is not only a visual experience but a constructed object—a handmade puzzle that reveals its logic through careful study.

Conceptual Underpinnings: Art as Intellectual Construction

Gris once described himself as “more interested in the construction of a picture than in its representation.” This philosophy is on full display in Abstraction. The painting resists narrative or emotional interpretation in favor of formal balance and intellectual rigor. It is a work that speaks to the mind as much as to the eye.

This approach aligns Gris with classical ideals, despite his modernist aesthetic. There is a sense of proportion, clarity, and symmetry that recalls Renaissance theory, even as the surface remains flattened and fragmented. Gris did not aim to distort reality arbitrarily; he aimed to reconstruct it according to a higher logic of visual order.

In Abstraction, Gris constructs a world in which form and idea are inseparable. The painting is not about any single object but about the principles of design—balance, contrast, harmony, and unity. These principles are conveyed through visual language, without the need for literal subject matter.

Historical Context and the Impact of 1915

The year 1915 was a pivotal moment in both European history and Gris’s artistic development. World War I was reshaping the cultural landscape, and artists across Europe responded by retreating into abstraction or seeking new visual languages to process a world in crisis.

Gris, a Spanish national living in France, did not serve in the military but was deeply affected by the war’s psychological toll. In this context, the clarity and restraint of Abstraction can be read as a response to chaos. While the world outside was fragmented by violence, Gris created a visual refuge governed by internal logic and compositional peace.

Moreover, 1915 was a year in which Gris reached new maturity as an artist. He completed a series of paintings that advanced Synthetic Cubism into realms of higher structure and more intense formal interplay. Abstraction belongs to this period of experimentation and refinement, revealing a painter at the height of his intellectual and artistic powers.

Influence and Legacy

Though often regarded as the “third man” of Cubism after Picasso and Braque, Juan Gris’s influence has grown in recent decades. His commitment to order, his mastery of color, and his fusion of abstraction with realism have made him a key figure in the evolution of modern art.

Abstraction exemplifies the kind of visual problem-solving that would later influence artists such as Josef Albers, Ellsworth Kelly, and even post-war architects. Gris’s insistence on painting as a constructed reality resonates with movements like Concrete Art, De Stijl, and even early Minimalism.

Furthermore, his ability to merge logic and lyricism places him in a unique position within the Cubist canon. Where Picasso is expressive and visceral, and Braque is moody and analytical, Gris is precise, poetic, and conceptually elegant.

Conclusion: The Poetry of Precision

Juan Gris’s Abstraction (1915) is more than an arrangement of geometric forms—it is a philosophical statement about what painting can be. In a time of upheaval and transformation, Gris offered an alternative vision: one of balance, intelligence, and visual harmony. His use of fragmented forms, layered space, and carefully calibrated color reflects a painter deeply engaged with the foundations of visual language.

In this painting, abstraction is not a rejection of reality, but a reimagining of it. Gris invites the viewer to consider the constructed nature of perception, the interplay of parts within a whole, and the enduring beauty of form in equilibrium.

Abstraction stands as a quiet revolution—a work that, despite its modest size and subdued emotional tone, challenges us to see art not just as representation but as a form of thought. It is a painting that rewards contemplation and affirms Gris’s place as one of the most sophisticated and visionary artists of the 20th century.