Image source: artvee.com

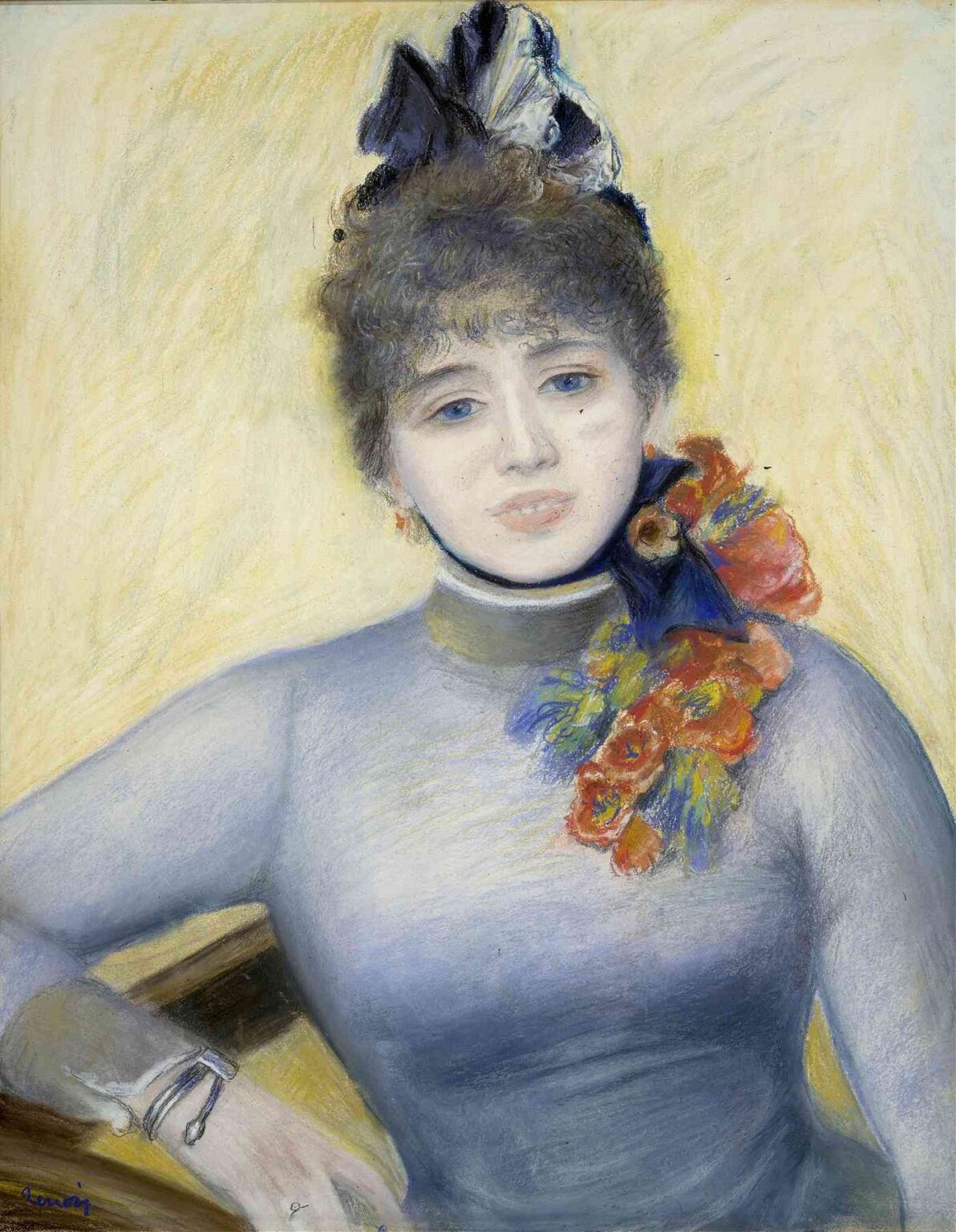

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s 1885 pastel portrait “Caroline Rémy” stands as a luminous testament to the artist’s mastery of feminine portraiture and his intimate engagement with the social figures of his time. Capturing the essence of Caroline Rémy—a French journalist, socialist, and feminist—this pastel work reveals both Renoir’s extraordinary sensitivity to texture and color and his ability to convey complex psychological presence through subtle expression and delicate execution.

Unlike many of Renoir’s more decorative female portraits, this image carries a quiet intensity and confidence that matches the historical role of Rémy herself. In a Belle Époque visual culture often defined by romanticized or passive representations of women, Renoir’s “Caroline Rémy” emerges as a rare and compelling portrait of intellectual elegance and self-awareness.

This in-depth analysis explores the visual, technical, and contextual elements of “Caroline Rémy”. We will examine the portrait’s composition, use of pastel, color symbolism, historical backdrop, and thematic resonance in relation to both Renoir’s style and the life of his sitter. In doing so, we’ll uncover how this work reflects not just a likeness, but an intimate artistic encounter with one of France’s pioneering female voices.

Historical and Biographical Context

The subject of this portrait, Caroline Rémy de Guebhard (1855–1929), was better known by her pen name Séverine. A journalist, activist, and champion of socialist and feminist causes, she was deeply involved in progressive politics in late 19th-century France. A close collaborator of Jules Vallès and an advocate for the oppressed, Rémy was one of the few women in her era to occupy a visible role in public intellectual life.

Renoir painted “Caroline Rémy” in 1885, at a moment when she had already begun to establish herself as a vocal political figure. This makes the work unusual in Renoir’s oeuvre. While he often painted bourgeois women, dancers, and family members, rarely did he choose subjects so clearly involved in radical thought and journalism. The decision to portray Rémy—whether by commission or invitation—signals an acknowledgment of her presence in cultural circles.

By this time, Renoir himself was moving away from the spontaneous brushwork of Impressionism toward a more structured, classical approach. His brushstroke tightened, and his figures gained volume and sculptural presence. Yet in this pastel, Renoir balances his newfound control with the softness and immediacy inherent to the medium, making it one of his most intimate portraits.

Composition and Framing

The portrait is executed in a half-length format, presenting Caroline seated in a relaxed yet upright posture. She gazes directly at the viewer, with a gentle tilt of her head and parted lips that suggest both curiosity and invitation. Her right arm bends at the elbow, resting confidently on a ledge or armrest, forming a natural compositional anchor.

Renoir’s composition keeps the background minimal—a textured yellowish cream that complements the cooler tones of her attire. This lack of distracting background elements helps center attention on the subject’s expression, posture, and attire. The framing is tight, emphasizing presence over setting and encouraging a direct emotional connection between viewer and sitter.

Despite its simplicity, the composition is highly effective. The strong diagonal of the right arm, the upright neck, and the slight asymmetry of the head’s position generate dynamic tension within the static pose. These elements create a subtle sense of movement and vitality, reinforcing the woman’s alert and intelligent character.

Use of Pastel: Texture and Technique

Unlike oil, pastel requires a unique sensitivity to surface and texture. Renoir embraces this fully in “Caroline Rémy”. The pastel is applied with layered softness in the face and neck, blending pinks, peaches, and grays to create delicate skin tones. This technique produces a luminous, lifelike appearance while preserving the matte finish characteristic of the medium.

In contrast, the hair and the floral corsage on her right shoulder are more gesturally rendered, with bolder strokes and less blending. The loose curls of her hair—executed in ash brown with lighter touches—capture both the volume and the informality of her style. Renoir uses textural variation to distinguish between skin, fabric, hair, and accessories without relying on outline or contour, allowing each area to breathe and harmonize.

The woman’s blouse or dress is made of a sleek, high-necked fabric rendered in shades of muted lavender and blue-gray. Its sheen is implied rather than detailed, conveyed through shifts in value rather than highlights. The use of pastel here is both sensitive and controlled, emphasizing the tactile qualities of fabric and flesh.

Color Palette and Symbolism

Renoir’s palette in this portrait is striking in its limited but harmonious range. The background’s pale yellow hues set a warm tonal stage, contrasting beautifully with the cooler, bluish-gray of the clothing. This juxtaposition creates a halo effect around the sitter’s head, lending her an aura of presence that subtly recalls religious iconography.

The most saturated area of the painting is the floral corsage near the collar, bursting with red-orange roses and vibrant blue accents tied together by a dark blue ribbon. These colors are not merely decorative; they inject vitality and contrast into the otherwise cool palette. Red has traditionally been associated with passion, vitality, and political conviction—qualities that align with Rémy’s life and legacy.

Additionally, the black and white ribbon or feather in her hair adds vertical emphasis and complements the palette with graphic contrast. These accessories underscore her individuality while suggesting the attention to fashion typical of upper-class women of the period.

Facial Expression and Psychological Insight

Caroline Rémy’s expression is one of the most compelling aspects of the portrait. Her pale lips form a gentle smile—ambiguous, quiet, and reflective. Her eyes are wide, gray-blue, and filled with quiet intensity. Rather than portraying exuberance or flirtation, Renoir opts for something more nuanced: calm thoughtfulness and watchful intelligence.

There’s a stillness to her face that invites interpretation. Is she skeptical? Warm? Curious? The slightly parted lips and tilt of the head imply an open conversation between sitter and viewer, an invitation to engage. This emotional ambiguity is rare in Renoir’s work and contributes to the lasting intrigue of the image.

What emerges is a portrait that balances formality and intimacy, idealization and realism. She is neither purely muse nor conventional socialite. Instead, she exists as a thinking, breathing individual—rendered with empathy and psychological depth.

The Role of Fashion and Ornamentation

While not overly elaborate, the fashion details in “Caroline Rémy” speak volumes about her social and cultural position. The high-necked blouse, detailed corsage, and ornamental hairpiece suggest sophistication and urbanity. These elements also reinforce her role as a woman straddling two worlds: one foot in the bourgeois aesthetic, the other in radical political engagement.

Renoir was a keen observer of textiles and accessories. In many of his portraits, clothing plays a symbolic role, indicating not just wealth but personality. Here, the simple elegance of the attire reinforces Rémy’s clarity of purpose, restraint, and inner strength.

Comparison to Renoir’s Other Portraits

When compared to Renoir’s more decorative and romantic portraits—such as “Jeanne Samary” or “Young Girl with a Hat”—“Caroline Rémy” is more reserved and grounded. There is less emphasis on sensual beauty or playful expression and more attention to character and self-possession.

This tonal shift likely reflects both the artist’s evolving style in the mid-1880s and the uniqueness of the subject. Where other Renoir women appear dreamy or performative, Rémy appears anchored, attentive, and confident. This distinguishes the work not only within Renoir’s oeuvre but also within the broader tradition of Impressionist portraiture.

Feminist and Political Subtext

Given Caroline Rémy’s stature as a feminist and leftist intellectual, it is impossible to view this portrait in isolation from its ideological implications. Though Renoir was not a political painter, his portrayal of Rémy suggests a degree of mutual respect and awareness of her influence.

The subtle strength in her gaze, the uprightness of her bearing, and the restrained elegance of her appearance all align with the image of a woman who was reshaping public discourse in France. She is not presented as a symbol of seduction but of self-contained dignity—an image far removed from the romantic clichés of the female muse.

Thus, “Caroline Rémy” functions not just as a portrait but as a visual assertion of feminine presence, intelligence, and autonomy within the artistic and cultural space of 19th-century France.

Legacy and Significance

Though perhaps lesser known than Renoir’s grander oil portraits, “Caroline Rémy” is a work of tremendous artistic and historical value. It captures a moment of intersection between high art and political reality, between pastel technique and feminist modernity.

In contemporary discussions of art and feminism, this portrait has regained relevance. It offers a counter-narrative to the objectified female bodies so common in 19th-century art. Instead, Renoir gives us a woman in command of her image, her thoughts, and her presence—rendered with tenderness and restraint.

The painting also reaffirms Renoir’s capacity for psychological depth, often overshadowed by his more decorative works. Here, pastel becomes a tool not only of softness and color but of expressive intimacy.

Conclusion: Portrait of a Mind and a Moment

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s “Caroline Rémy” is a rare achievement in portraiture: visually harmonious, psychologically penetrating, and historically resonant. Through his deft handling of pastel, Renoir brings to life not just a beautiful woman, but a complex, independent figure whose legacy continues to inspire.

At once intimate and public, elegant and grounded, the portrait affirms the power of visual art to engage with personality, identity, and ideology. Caroline Rémy gazes back at us not as a fantasy, but as a real presence—an icon of intellect, expression, and quiet strength in the heart of fin-de-siècle France.