Image source: artvee.com

Wassily Kandinsky’s “Klänge Pl.23” (1913) stands as a landmark in the evolution of modern art—an intersection of image and sound, narrative and abstraction. Created as part of his Klänge (“Sounds”) portfolio, a pioneering artist’s book composed of woodcuts and poetic prose, this particular plate—Plate 23—illustrates the synesthetic fusion Kandinsky believed was essential to artistic expression. Here, visual form is liberated from the traditional constraints of representation, transforming into a symbolic language of intuition, spirituality, and inner resonance.

As one of the founders of abstract art, Kandinsky’s mission was not merely to depict objects or scenes, but to convey spiritual truths through color, line, and rhythm. The Klänge series is both a culmination of his early theoretical exploration and a precursor to his later, fully non-objective compositions. Pl.23 occupies a vital moment within that journey—a moment where figuration still exists, but is becoming secondary to mood, movement, and the internal “sound” of the image.

In this analysis, we will explore “Klänge Pl.23” in detail: its historical context, compositional and formal qualities, use of color and abstraction, symbolic elements, and its broader significance in Kandinsky’s work and in the history of modernism.

Historical Context: Kandinsky’s Synesthetic Vision

Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) was a painter, printmaker, and theorist whose work defined the birth of abstraction. Originally trained in law and economics, Kandinsky turned to art after being struck by Monet’s Haystacks and deeply influenced by music—especially Wagner’s compositions and Schoenberg’s atonality. For Kandinsky, art was not just a visual language—it was a spiritual force capable of transcending the material world.

Between 1909 and 1913, Kandinsky lived in Munich and was involved with the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), which he co-founded with Franz Marc. During this time, he published his landmark theoretical text Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), and began working on Klänge, a collection of prose poems accompanied by woodcuts, completed in 1913.

The title Klänge, meaning “Sounds,” reflects Kandinsky’s synesthetic belief that visual and musical experiences are interconnected. His prints are visual counterparts to his writing—impressions, emotions, and dreamlike fragments rendered in color and form. Pl.23 is emblematic of this holistic vision: it is not a literal scene, but a symbolic soundscape.

Composition and Layout

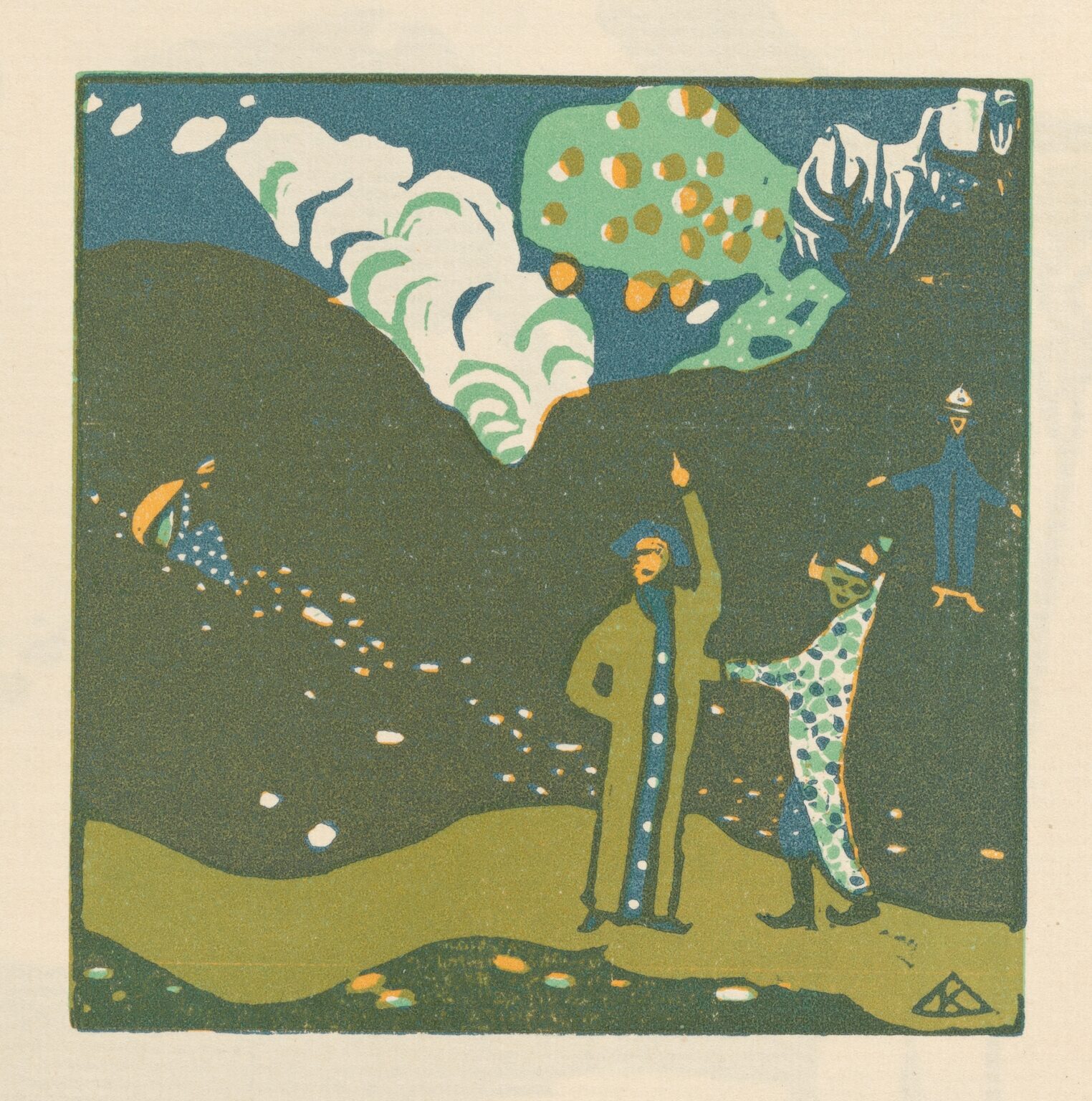

At first glance, “Klänge Pl.23” is playful, even whimsical. Five stylized figures are arranged across a loosely defined landscape, with two central figures dominating the composition. One points upward toward a fantastical sky, while the other gestures across the canvas. Their elongated bodies, stylized clothing, and simplified postures evoke puppets or paper cutouts—both theatrical and naive in form.

The background consists of gently undulating hills rendered in green and dark olive tones. Above, strange organic shapes hover—white clouds with emerald swirls, a green patch dotted with orange circles, and what appears to be a crystalline formation in the upper right. These sky forms defy natural logic and instead suggest a dream or cosmic vision. They may represent celestial bodies, emotions, or abstract energies.

The figures are connected not by a literal narrative but by rhythm and motion. Their poses create diagonals and visual echoes. The viewer’s eye travels from the leftmost figure—small and nearly lost in the hills—to the more defined figures on the right. The floating figure in blue, seemingly suspended mid-air, adds a sense of surrealism and metaphysical suspension.

The compositional space in Pl.23 is not realist but symbolic. Perspective is flat, depth is compressed, and scale is arbitrary. This flattening emphasizes the image’s internal harmony and symbolic content over spatial realism.

Color and Abstraction

Kandinsky’s use of color in Pl.23 is deliberate, harmonious, and expressive. The dominant palette consists of deep greens, muted blues, soft ochres, and bursts of orange and white. These tones do not reflect natural lighting or realistic rendering; instead, they evoke mood and emotional resonance.

The color choices create visual vibrations. The contrast between the forest green hills and the minty white clouds creates a surreal, almost musical tension. The orange polka dots on the upper green mass act as visual staccato, while the emerald swirls within the clouds mimic melodic movement.

Importantly, Kandinsky believed that color could act independently of form. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, he theorized that blue calls to the spiritual, yellow is earthly and exerts pressure, and red represents inner vitality. While Pl.23 doesn’t conform rigidly to this system, it reflects these principles intuitively. The interplay of colors does not describe but expresses.

The abstraction of the background reinforces the autonomy of the painting’s elements. Trees, sky, and ground exist not as mimetic representations but as compositional energies. Each shape, color, and figure contributes to the visual symphony—each note in Kandinsky’s silent music.

Symbolism and Narrative Interpretation

Though Pl.23 resists straightforward narrative, it is rich in symbolic suggestion. The central figure pointing skyward may signify spiritual aspiration or visionary insight. He stands as a prophet, a mystic, or a guide—inviting both the figure beside him and the viewer to look beyond the visible.

The figure to his right, wearing dotted clothing, appears to be in conversation or instruction. This could signify dialogue—between the earthly and divine, between self and other, or between rationality and imagination. Together, these two central figures echo ancient depictions of magi, philosophers, or spiritual seekers.

The floating figure in blue, seemingly unmoored from gravity, could symbolize transcendence, divine inspiration, or liberation from earthly concerns. He hovers in a space untethered to the ground, like an idea or spirit.

The small figure in the lower left may represent the beginning of a path—a journey toward understanding. His smallness and position in the corner reinforce his role as initiator or seeker, gradually making his way toward the revelation that the larger figures seem to be contemplating.

Kandinsky often drew upon Theosophy, folklore, and his own dreams to populate his compositions. Thus, Pl.23 functions less like a linear story and more like an allegorical scene. Each element contributes to a mood of discovery, elevation, and metaphysical exploration.

Stylistic Influence and Technique

Pl.23 is executed in woodcut—a medium that Kandinsky valued for its primitive, direct, and expressive qualities. The woodcut allowed him to simplify forms, emphasize bold outlines, and play with negative space. It also connected him to earlier printmaking traditions, particularly medieval and folk art, which he admired for their spiritual authenticity.

The influence of Japanese woodblock prints is also evident. Like Hokusai or Hiroshige, Kandinsky flattens space, uses expressive contours, and prioritizes harmony of shape and color over mimetic accuracy.

Kandinsky’s earlier training in Russian folk ornamentation and icon painting also informs this work. The stylized figures, decorative motifs, and spiritual overtones all reflect these roots. Yet, in fusing them with avant-garde experimentation, Kandinsky created something entirely new—a hybrid of tradition and abstraction.

Connection to Poetry: Visual and Verbal Klang

Klänge was never meant to be a standalone image series. It was conceived as an artist’s book—a total artwork (Gesamtkunstwerk) that blended visual prints with prose poems. Kandinsky’s accompanying texts are impressionistic, absurdist, and rhythmically charged. They mirror the visual elements in tone and mood, further blurring the boundary between disciplines.

While Pl.23 has no direct poem attached to it, its spirit reflects the themes of the book as a whole: transformation, musicality, and inner revelation. Kandinsky likened his poems to musical improvisations, and the prints to silent scores. Together, they express a unified synesthetic vision—art not just seen, but heard and felt.

In this way, Pl.23 is not just an illustration but a performance—a visual echo of an internal sound. Its title, while neutral, implies its part in a larger sequence—a tone, a cadence, a “note” in the broader visual symphony that is Klänge.

Influence and Legacy

“Klänge Pl.23” and the entire Klänge series occupy a foundational place in the development of abstract and conceptual art. Alongside Concerning the Spiritual in Art and later works like Composition VII, this woodcut helped define Kandinsky’s philosophical and visual program.

The emphasis on synesthesia, abstraction, and the unity of the arts influenced many key figures of 20th-century modernism, including Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, and the Bauhaus movement. It also anticipated later developments in visual poetry, artist’s books, and experimental printmaking.

Today, Pl.23 remains a testament to the power of intuition and the search for a universal visual language. It embodies the conviction that art need not imitate the world to reveal truth—that abstraction can be as emotionally and spiritually resonant as any realistic portrayal.

Conclusion: A Silent Sound in Visual Form

Wassily Kandinsky’s “Klänge Pl.23” is not a mere picture. It is a distilled expression of his revolutionary belief that art could transcend material reality and awaken the spiritual in the viewer. Through its whimsical figures, floating symbols, and harmonic colors, the image becomes a kind of pictorial music—an echo of inner sound.

Created in a time of artistic upheaval and philosophical exploration, the print bridges the old and the new, the figurative and the abstract, the seen and the sensed. It invites viewers to abandon literal interpretation and instead engage with the painting on a deeper, intuitive level.

Pl.23 continues to resonate because it refuses to be confined. It is not just part of a book—it is part of a vision. A vision that sees art as language, rhythm, and revelation.