Image source: artvee.com

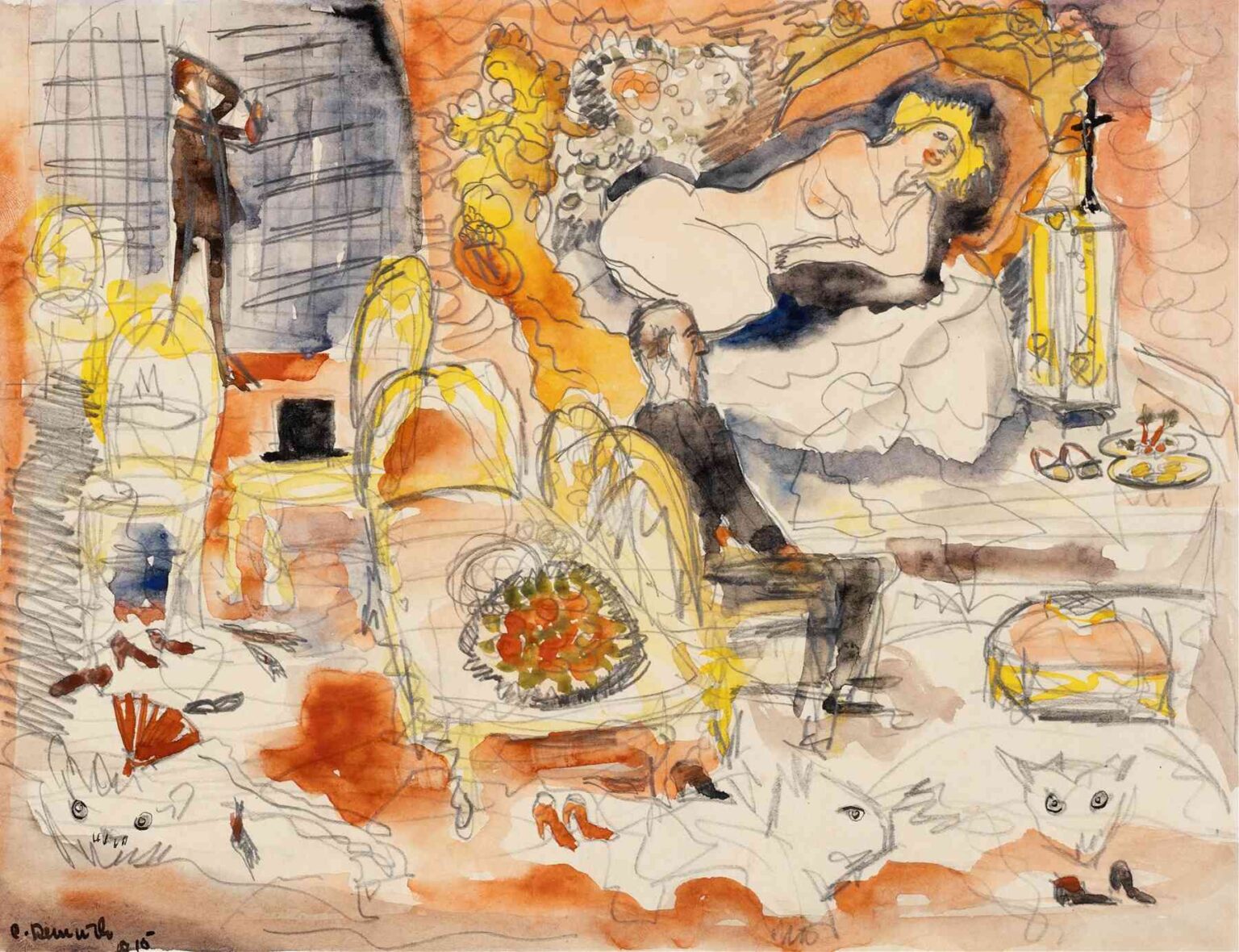

Charles Demuth’s “Count Muffat Discovers Nana with the Marquis de Chouard” (1915) is a vivid and psychologically complex watercolor that merges literary illustration with Symbolist expression. Created during a pivotal time in Demuth’s career, the painting is both a tribute to Émile Zola’s controversial novel Nana (1880) and a radical reinterpretation of narrative illustration in early 20th-century American art. Through a playful yet unsettling blend of line, color, and composition, Demuth captures a moment of dramatic revelation steeped in themes of decadence, voyeurism, and the disintegration of moral facades.

The scene represents a key moment from Zola’s novel, when Count Muffat discovers Nana, the beautiful and scandalous courtesan, in a compromising position with his father-in-law, the Marquis de Chouard. Rather than render the scene with strict realism, Demuth adopts a fluid, dreamlike approach. The composition is a swirl of fragmented figures, suggestive contours, and theatrical flourishes. The viewer is not just observing an event—they are drawn into the emotional and psychological undercurrents that drive the characters’ actions.

This analysis will explore the painting’s literary context, formal elements, symbolic resonances, and place within both Charles Demuth’s oeuvre and the larger history of American modernism. It will argue that “Count Muffat Discovers Nana” is not only a literary homage but a sophisticated meditation on performance, eroticism, and the boundaries between public and private personas.

Literary Context: Zola’s “Nana” and Naturalist Morality

Demuth’s painting draws directly from Émile Zola’s Nana, a novel emblematic of French Naturalism that caused considerable scandal upon its release. The novel follows the rise and fall of Nana Coupeau, a Parisian prostitute who ascends to power in elite society, seducing and ruining a string of powerful men. Zola’s narrative is both a critique of Second Empire decadence and a study of the corrupting influence of beauty and sexual power.

The specific scene depicted by Demuth—Count Muffat discovering his wife’s father in bed with Nana—is one of ultimate humiliation. It encapsulates the unraveling of bourgeois respectability in the face of unrestrained desire. For Zola, this is a moment of narrative climax and social indictment. For Demuth, it becomes a stylized tableau, dripping with irony, sensuality, and the melodrama of theatrical spectacle.

Demuth, a known bibliophile with a particular fondness for French literature, would have understood the novel’s socio-political weight. But rather than illustrate it didactically, he transposes it into a dreamlike vision, rich in emotional ambiguity.

Composition and Visual Language

The painting’s composition is crowded and chaotic, yet deftly orchestrated. It is constructed with an overlay of sinuous pencil lines, washes of transparent watercolor, and areas of opaque pigment. This creates a sense of layering, as if the image is simultaneously emerging and dissolving. The viewer’s eye is drawn across the page in a zigzag motion—first to the reclining figure of Nana at the top right, then to Count Muffat seated below her, and finally to the shadowy intruder on the left, presumably the Count himself or possibly a servant in shock.

Nana reclines on a lavish bed surrounded by plush drapery and florals, rendered in bursts of orange and gold. Her nude form is central to the composition, her gaze nonchalant, her body illuminated like a stage performer caught mid-curtain call. This theatricality underscores Nana’s self-awareness and power as both object and agent of desire.

The central male figure, seated rigidly in a chair, is Count Muffat—his posture one of stunned paralysis. His gray suit and turned back suggest emotional distance and moral collapse. Above and behind him are spectral chairs, empty and echoing with absence, perhaps symbolizing social expectations or abandoned propriety.

Demuth’s spatial treatment resists realism. The foreground and background merge, and perspectives are skewed. Furniture floats. Shadows are rendered not through light but line. The figures seem weightless, dreamlike. This disorientation mirrors the emotional collapse taking place.

Line, Color, and Technique

Demuth’s use of line is central to the painting’s expressive power. His pencil strokes are fluid and improvisational, suggesting motion, instability, and emotional turbulence. These lines blur the boundary between figure and environment, contributing to the sense that the characters are not fixed identities but psychological states.

Color, meanwhile, is used sparingly but purposefully. The dominant hues—burnt orange, mustard yellow, soft peach, and smoky gray—evoke a decadent, overheated atmosphere. They also underscore the duality of warmth (desire, intimacy) and decay (moral erosion, shame). The red high heels, carelessly abandoned near the foot of the bed, function as sensual metonymy—suggesting both seduction and the literal ‘stripping away’ of social pretense.

One of the most notable techniques in this painting is Demuth’s semi-translucent layering. The watercolor medium allows for ghostly traces of previous marks, creating a sense of memory and psychic residue. This is especially powerful in a scene rooted in betrayal and emotional rupture.

Symbolism and Emotional Subtext

While Demuth never moralizes, his painting is rich with symbolic implication. Nana, reclining nude amid florals and finery, represents not just a woman but a force of nature—a muse, a siren, a destabilizing agent of desire. She occupies the painting’s most illuminated and ornamental space, suggesting her status as both goddess and commodity.

The presence of food, shoes, flowers, and wine—all painted with loose delicacy—reinforces themes of sensual pleasure and overindulgence. The viewer is reminded not only of the carnal but of consumption, appetite, and excess—key themes in Zola’s original novel.

Count Muffat’s gray figure, meanwhile, stands in stark contrast. He is rendered in more precise lines, his posture frozen in place. This visual stillness suggests shock, impotence, or paralysis. His presence evokes pity, but also critique: the collapse of bourgeois moral codes when confronted with naked truth.

The secondary figure in the background—darkly silhouetted near window bars—may be an external witness or a symbolic reflection of guilt and self-surveillance. It reinforces the idea that this moment is both public and private, theatrical and real, scandalous and intimate.

Gender, Performance, and Modern Identity

Demuth was a queer artist working in an era where open expressions of sexuality—particularly non-normative sexuality—were taboo. As such, his engagement with Nana, a novel about sexual performance, control, and societal disintegration, becomes even more significant.

In “Count Muffat Discovers Nana”, Demuth turns the gaze on the mechanisms of desire. Nana is not merely a nude figure; she is the director of the scene. Her passive posture masks active power. She holds the gaze of the viewer and manipulates the narrative. Count Muffat, by contrast, is powerless—caught in a web of his own contradictions.

This reversal plays with traditional gender dynamics in art history, wherein the female nude is often passive and objectified. Demuth, however, imbues Nana with agency and theatrical savvy. She is at once character and author of the spectacle, both mythologized and self-aware.

Placement in Demuth’s Career and American Modernism

Charles Demuth (1883–1935) is most often associated with Precisionism, a movement defined by sharp-edged industrial forms and architectural abstraction. However, his early work—especially from 1910 to 1917—was rooted in Symbolism, watercolors, and literary themes. This period saw him produce a series of works inspired by Oscar Wilde, Henry James, and Émile Zola.

“Count Muffat Discovers Nana” fits squarely into this early phase. It demonstrates Demuth’s love of European literature, his experimentation with watercolor and line, and his interest in theatricality and identity. It also reveals his ability to fuse narrative content with modernist form—replacing descriptive realism with emotional suggestion.

In this sense, the painting is a bridge between the literary past and visual future. It presages the minimal elegance of his later Precisionist works while maintaining the emotional volatility of his Symbolist origins.

Reception and Legacy

While Demuth’s watercolors remained underappreciated during his lifetime, they have since been re-evaluated as crucial to understanding his broader practice. “Count Muffat Discovers Nana” is now seen as a precursor to narrative abstraction and an important exploration of gendered gaze, erotic charge, and performative identity.

Contemporary critics often highlight its cinematic quality—its ability to freeze a moment of scandal and allow the viewer to examine every thread of its emotional and symbolic texture. The painting is not an illustration but a dramatization—a reinterpretation of literature through the lens of personal sensibility and modernist innovation.

Conclusion: A Scandal Reimagined in Line and Color

Charles Demuth’s “Count Muffat Discovers Nana with the Marquis de Chouard” is far more than an adaptation of a literary episode. It is a layered visual narrative, a meditation on identity, desire, and the collapse of appearances. Through sinuous line, expressive color, and theatrical composition, Demuth transforms Zola’s moment of scandal into a Symbolist reverie—ambiguous, charged, and emotionally resonant.

This painting stands as a testament to Demuth’s unique artistic voice—bridging literature and abstraction, figuration and fantasy. It captures a fleeting instant not with photographic accuracy but with the heightened sensitivity of a dream or memory. In doing so, it elevates gossip to allegory, and spectacle to art.