Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: Sargent’s Command of the Portrait

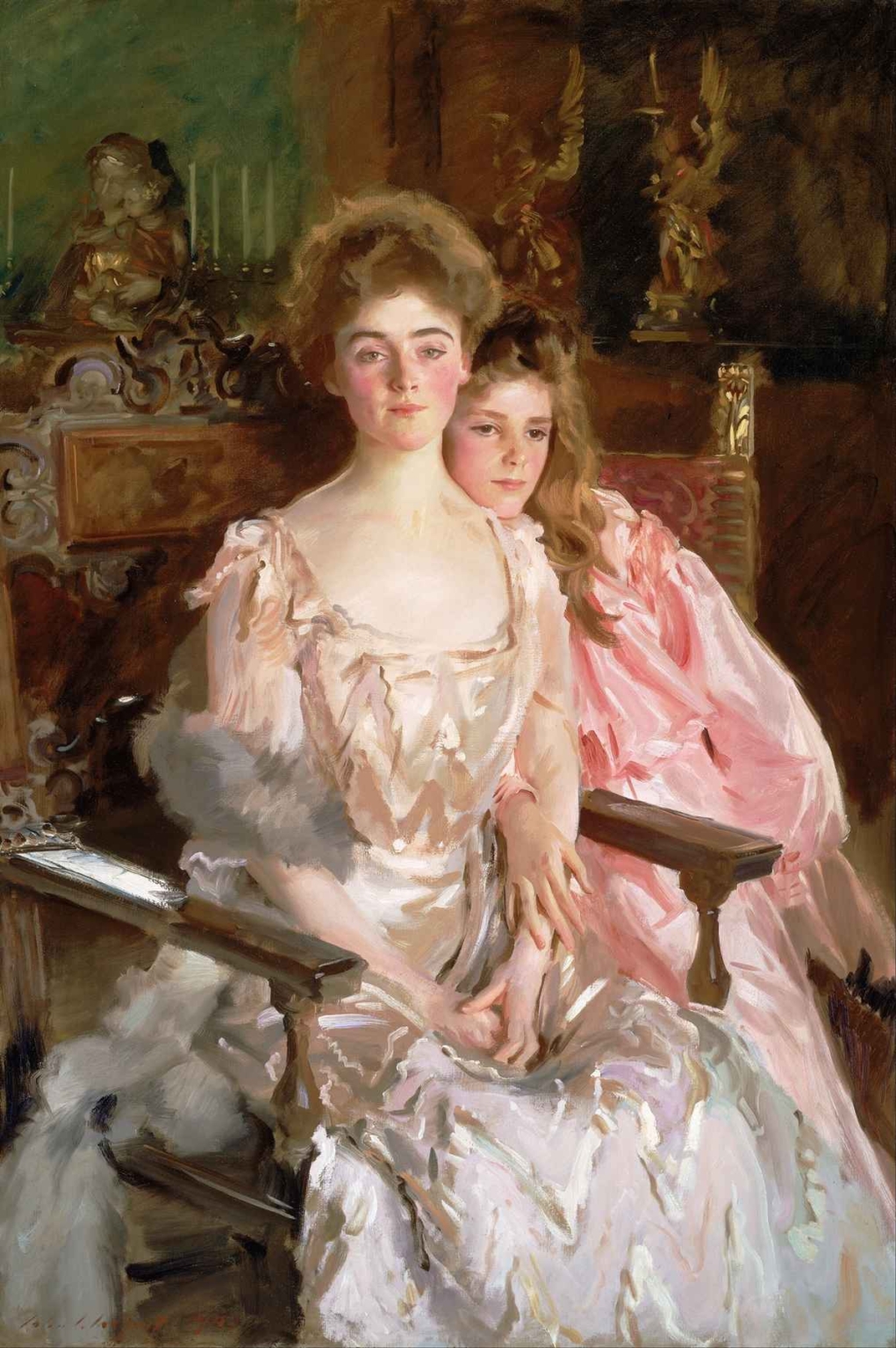

John Singer Sargent is regarded as one of the most accomplished portraitists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Renowned for his dazzling technique and ability to capture the psychological nuances of his subjects, Sargent immortalized an elite world in paint—a world shaped by class, fashion, and transatlantic sensibility. Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel, painted in 1903, exemplifies this mastery.

Commissioned during the height of the Gilded Age, this portrait does more than flatter its subjects—it articulates the social ideals, domestic roles, and aesthetic aspirations of a particular class of American aristocracy. Combining intimacy with opulence, it reveals not only the identity of its sitters but also the cultural fabric they inhabit.

Historical and Social Context: A Portrait of Prestige

Gretchen Osgood Warren, a Boston socialite, poet, and patron of the arts, belonged to a family deeply embedded in the intellectual and cultural elite of the city. Her husband, Fiske Warren, was a paper manufacturer and a progressive social reformer. In commissioning Sargent, the Warrens aligned themselves with a painter known for portraying European nobility and American expatriates in Paris and London. This act was both personal and strategic—it was a statement of cultural capital.

The early 1900s were a time of intense stratification in American society. Portraiture played a key role in asserting one’s place within it. Sargent’s clients sought more than a likeness—they wanted legacy. This dual portrait, then, serves both as a tribute to maternal affection and a monument to social distinction.

Composition: Elegance and Intimacy Intertwined

The composition immediately commands attention through its composure and sophistication. Mrs. Warren is seated in an ornately carved chair, her torso turned outward toward the viewer, while her daughter Rachel leans into her from behind. Their physical closeness conveys maternal tenderness, but the symmetry and staging lend a formality that anchors the image in tradition.

Sargent’s careful positioning allows the viewer to engage with both figures on distinct emotional terms. Mrs. Warren’s upright posture, poised gaze, and gloved hand resting gracefully over Rachel’s reflect a sense of calm authority. Rachel, by contrast, is more vulnerable—her head tilted toward her mother, her expression reserved yet trusting. The result is a dynamic interplay of public and private identities within a single frame.

The placement of the figures against a richly detailed background—a dimly lit interior with gilded statuary and candelabra—further emphasizes their presence. The luxurious setting does not overwhelm the sitters but enhances their sense of refinement and importance.

Use of Color and Texture: Sargent’s Painterly Brilliance

One of the defining features of this portrait is Sargent’s virtuosic handling of paint. He captures the soft glow of satin, the gossamer quality of tulle, and the rosy translucence of skin with remarkable precision. Yet his technique never feels rigid. Instead, it breathes with vitality.

Mrs. Warren’s gown—a lustrous white tinged with blush and ivory—cascades in rippling folds across her lap. Its reflective surface interacts subtly with the ambient light, drawing the viewer’s attention to her centrality. Rachel’s pink dress, rendered in looser, more abstract brushstrokes, contrasts with her mother’s more refined garment. This distinction underscores their differing roles—womanhood versus girlhood, maturity versus youth.

Sargent’s color palette is rich yet restrained. The warm tones of the skin and fabrics are balanced against the dark green and brown tones of the backdrop. The few golden accents, like the carved chair arms and bronze figurines in the background, provide visual punctuation without excess.

His brushwork oscillates between the meticulously controlled and the suggestively fluid. The facial modeling, particularly in Mrs. Warren, is smooth and sculptural, while the hands and textiles exhibit a looser style that speaks to Sargent’s Impressionist leanings.

Gesture and Expression: Dual Portraiture and Psychological Insight

What sets this portrait apart from many society commissions is its emotional complexity. Mrs. Warren’s expression is composed, almost enigmatic. She appears confident but not cold, aware of being observed but not entirely exposed. Her gaze is neither confrontational nor dismissive—it meets the viewer with poised detachment.

Rachel, in contrast, seems quietly contemplative. Her eyes are lowered slightly, her mouth nearly expressionless, her body partially obscured by her mother’s. This layering creates a symbolic image of protection and inheritance. The daughter is not simply a figure of affection; she is an extension of her mother’s identity, part of a lineage and a social ideal.

The interlocking hands—Mrs. Warren’s gently encircling Rachel’s—convey connection and continuity. This small gesture, rendered with extraordinary grace, serves as the emotional fulcrum of the painting. It bridges the two figures both physically and symbolically, suggesting care, education, and legacy.

Symbolism and Setting: Wealth as Background, Not Spectacle

Though the portrait is saturated with signs of luxury—sumptuous fabrics, ornate furnishings, and golden statuary—it never slips into vulgar display. Sargent, astutely, uses these elements as context rather than content. The richness of the environment reinforces the figures’ social position but never upstages their humanity.

In fact, the spiritual tone of the background—dim lighting, flickering candles, angelic sculptures—infuses the portrait with a quiet reverence. The scene reads almost like a domestic altar, with mother and child at its center. This association aligns with ideals of the time, which linked womanhood to moral elevation and the home to sacred space.

Such choices reflect the tensions of the Gilded Age: opulence coexisting with restraint, modernity embedded in tradition. Sargent walks this tightrope masterfully, delivering a painting that flatters its subjects while still offering a subtle commentary on their world.

Aesthetic Lineage: Echoes of Old Masters

Art historians have long noted Sargent’s debt to the Old Masters. In Mrs. Fiske Warren and Her Daughter Rachel, echoes of Velázquez, Van Dyck, and Gainsborough abound. The composition recalls the Spanish court portraits in its dignity and depth, while the textural realism harks back to Dutch painting. Sargent’s genius lay in his ability to modernize these influences without mimicking them.

The fusion of old-world grandeur with contemporary vitality made Sargent especially appealing to wealthy American patrons. They sought in his portraits a bridge between their modern affluence and the aristocratic traditions of Europe. In this regard, Mrs. Fiske Warren and Her Daughter Rachel is both a personal keepsake and a cultural performance.

Reception and Legacy

When the painting was first exhibited, it was widely praised for its elegance and technical brilliance. Today, it continues to be celebrated as one of Sargent’s most psychologically nuanced portraits. It stands as a testament to his ability to balance likeness with atmosphere, realism with abstraction, surface beauty with emotional depth.

Beyond its aesthetic value, the portrait offers insights into gender, class, and identity at the dawn of the 20th century. It captures the performative nature of femininity in an era when women were expected to embody both refinement and restraint. It also immortalizes a moment of maternal intimacy, rendered without sentimentality yet full of warmth.

For contemporary viewers, the painting serves as a lens into a vanished world, but also as a mirror for enduring questions: What do portraits say about us? What do we choose to show, and what remains hidden?

Conclusion: A Portrait of Presence and Poise

Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel is more than a display of painterly prowess—it is a meditation on beauty, lineage, and the interplay between public image and private affection. Through brushwork both assertive and delicate, Sargent captures not only the appearance of his subjects but the aura they project: of grace, intellect, and familial closeness.

It remains one of the finest examples of Sargent’s ability to elevate portraiture into a form of psychological and cultural storytelling. The viewer is left not merely with a memory of two figures in silk, but with a lingering sense of who they were, and what they represented in their time—a mother and daughter enshrined in paint, symbols of elegance and enduring connection.