Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: Munch Beyond “The Scream”

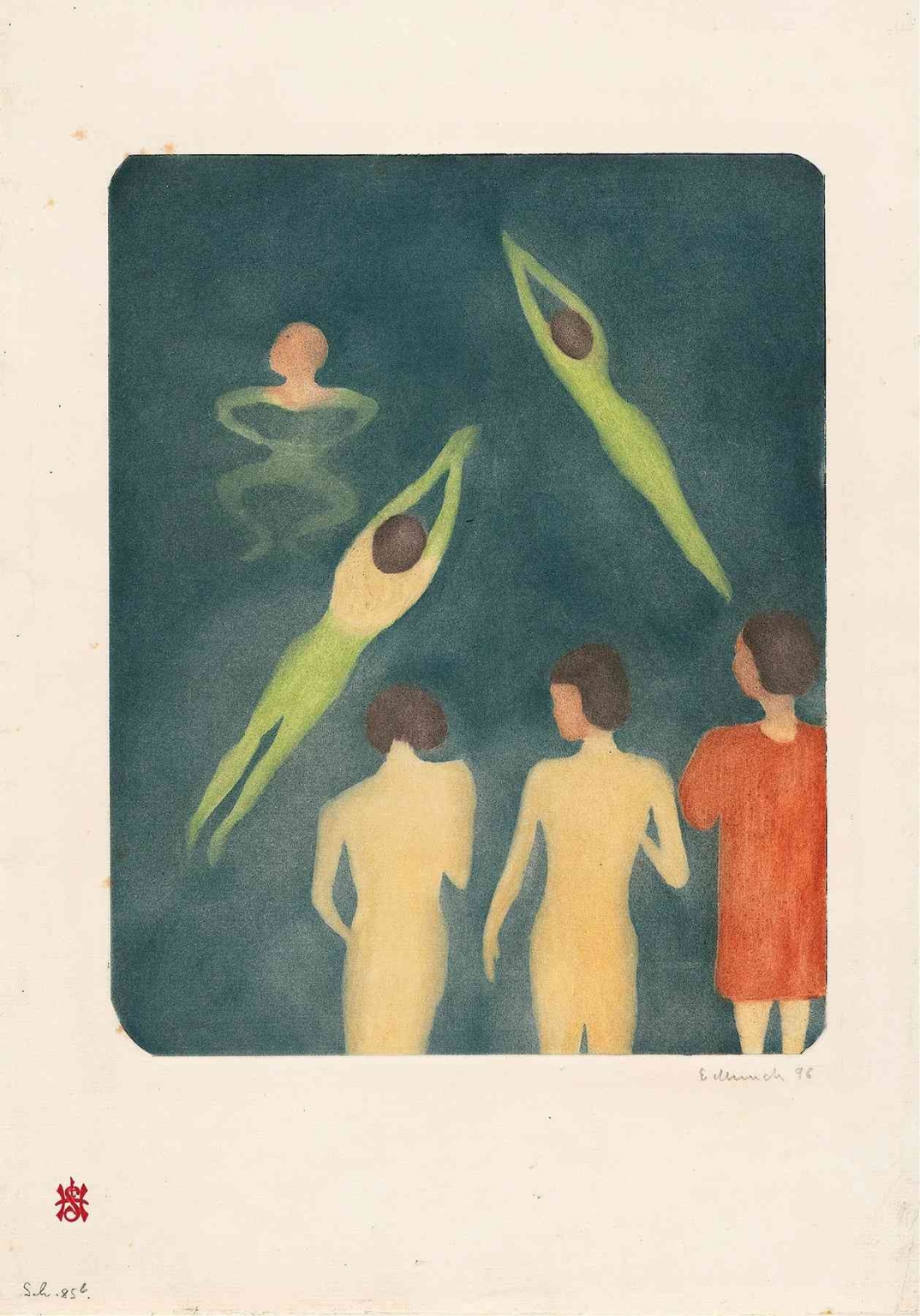

When most think of Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893) dominates the conversation. However, the breadth of Munch’s oeuvre reveals a far more nuanced and diverse body of work. Boys Bathing, created in the late 1890s, shows another side of the artist—one less consumed with existential anguish and more preoccupied with the quiet rituals of life, particularly those linked to youth and nature.

Painted in soft pastels and washed hues, Boys Bathing stands apart for its minimalist composition and emotional restraint. In place of Munch’s typical swirling lines and dramatic faces, we are given a nearly abstracted moment of gentle movement, subtle social interaction, and human vulnerability. Through this seemingly modest scene, Munch creates a tender psychological landscape—a vision of boyhood as fragile, ephemeral, and hauntingly beautiful.

Context: Bathing as a Cultural and Artistic Theme

In the late 19th century, outdoor bathing was not merely a hygienic or recreational act—it was also a rite of passage, a symbol of freedom and camaraderie. Particularly in Scandinavia, swimming in natural waters was considered part of a wholesome, often idealized connection with nature.

Artists across Europe—from Thomas Eakins in the United States to Paul Cézanne in France—engaged with the motif of bathers to explore the human body, leisure, and innocence. Yet, for Munch, this scene transcended any academic interest in anatomy. Rather, it presented a way to contemplate identity in its most formative stage: adolescence. In Boys Bathing, the figures are not individualized with detailed features; they are silhouettes, bodies in motion and repose, figures poised on the edge of consciousness.

The choice to depict boys, rather than adult men, is also telling. Munch’s interest in psychology, shaped by personal loss and illness, often turned toward transitional life stages—childhood, puberty, aging. The boys in this image represent a liminal state between innocence and awareness, vulnerability and strength.

Composition: From Shoreline to Silence

The composition of Boys Bathing is both simple and sophisticated. The image is structured vertically, with the swimmers occupying the top half of the frame and the onlookers grouped along the bottom. The majority of the space is taken up by the deep, teal-colored water, a visual and symbolic expanse that separates figures from one another while connecting them in shared experience.

Munch arranges the swimmers in various stages of action. One boy is submerged, his form distorted into an ethereal green. Two others are mid-dive, elongated in shape and tinted in ghostly greens and yellows. Below them, three boys stand at the water’s edge—two nude and one clothed in red, whose presence disrupts the rhythm of the composition and introduces narrative ambiguity.

Their poses are static, contemplative. They are not about to jump in, nor do they react to the swimmers. They merely observe—perhaps with longing, trepidation, or simple stillness. This separation between the swimmers and watchers is key to the painting’s emotional resonance.

The Use of Color: Atmosphere Over Detail

Munch’s use of color in Boys Bathing is understated but intentional. The dominant tone is the bluish-green of the water, which serves both as setting and mood. This shade—deep, cool, and slightly opaque—creates a sense of introspection and dreamlike unreality. The absence of any vivid natural detail (trees, rocks, waves) furthers this atmosphere of quiet otherworldliness.

The figures themselves are rendered in pale oranges, yellows, and muted greens, with the exception of the boy in red, who stands out like a beacon. This use of contrast guides the eye directly to him, prompting questions about his role in the scene. Is he an outsider? A guardian? A boy not yet ready—or no longer able—to participate?

Munch avoids hard outlines, instead opting for soft edges and gentle transitions. The result is a visual haze that mirrors the memory-like quality of the moment. This is not a painting of an event, but the recollection of one—fuzzy around the borders, yet emotionally precise.

Themes: Youth, Alienation, and Observation

At its heart, Boys Bathing is a meditation on youth and the subtle dynamics of group identity. It captures that fleeting stage of life where the body begins to change, friendships become more complex, and the world opens up as both inviting and intimidating.

The boys in the water are liberated, moving gracefully in sync with nature. Those on the shore, however, represent the opposite—they are self-aware, physically restrained, possibly excluded. The clothed figure, in particular, introduces a layer of psychological distance. Is he too shy to swim? Has he just arrived? Is he older, younger, or simply different?

These questions are never answered because Munch is not telling a specific story. Instead, he evokes the universal experience of standing on the edge—of a pool, a group, or a moment in life—and watching others move forward while you hesitate.

In many ways, the painting can be read as a metaphor for the artist himself. Munch, who often felt alienated and was known for his emotional intensity, may have identified more with the observer than the participants. His entire artistic project, after all, revolved around watching—studying, remembering, and transmuting lived experience into visual poetry.

Psychological Underpinnings: Munch’s Symbolist Lens

Though Boys Bathing lacks the overt symbolism of Munch’s more famous works, it is deeply informed by his Symbolist orientation. Symbolism in the late 19th century was not about creating icons or allegories, but about expressing inner states—moods, fears, and emotional truths—through distilled, often dreamlike imagery.

Here, the dream is of youth, but one tinged with melancholy. The distance between figures, the absence of facial expressions, the soft dissolve of outlines—all contribute to a sense of emotional disconnection beneath the surface unity.

There is also an undercurrent of sensuality, though it remains subtle. The nude figures are not eroticized, but they are observed with a certain reverence. Their forms are smooth, idealized, anonymous. The presence of the clothed figure only heightens this tension between exposure and concealment, intimacy and separation.

This psychological ambiguity is one of the painting’s greatest strengths. It does not impose a narrative or demand a reaction. Instead, it invites viewers into a space of quiet introspection—a space that is both specific to Munch and universal to memory.

Technique: Lithography and Soft Forms

Boys Bathing is not an oil painting but a color lithograph—a choice that influences both its appearance and tone. Lithography allowed Munch to experiment with flat planes of color and simplified forms, both hallmarks of his print work. It also lent itself to the diffuse, grainy textures seen here, which enhance the feeling of looking at an old memory or a foggy recollection.

Unlike his more expressionistic works, where brushwork is aggressive and layered, this print relies on smooth transitions and minimal detailing. The result is a quiet surface—nothing juts out, nothing demands attention. Everything flows.

This restraint is part of the work’s power. It allows the viewer to linger, to observe, and to project their own associations onto the scene. In many ways, it exemplifies the Symbolist idea that art should not declare, but suggest.

The Figure in Red: Interpretation and Ambiguity

Much has been said about the clothed figure in red. Art historians and critics have offered varying interpretations—some see him as an outsider, others as a symbol of repression or social difference. One common reading is that the figure represents Munch himself, inserted into the scene as both participant and observer.

The choice of red is especially significant. It breaks the harmony of the composition and suggests something emotionally charged—perhaps desire, perhaps shame, perhaps simply separateness. That this figure is not fully nude, like the others, reinforces the idea of psychological boundary. He is both near and far, included and excluded.

It’s worth noting that this duality recurs in much of Munch’s work. Figures often appear disconnected from their environment or from one another, as if existing in their own emotional worlds. Here, that sense of psychological isolation is captured with exceptional subtlety.

Legacy: A Quiet Masterpiece

Though not as well-known as The Scream or Madonna, Boys Bathing holds a unique place in Munch’s career. It reveals a quieter, more contemplative side of his art—one less dominated by overt symbolism and more invested in the poetics of everyday life.

It also foreshadows many of the themes that would later emerge in modernist art: the exploration of adolescence, the fragmentation of social identity, the abstraction of form to express emotion. In its soft lines and muted tones, we see the beginning of a visual language that would influence later artists from the German Expressionists to early abstractionists.

More than anything, the painting captures a fleeting moment—a summer day, a group of boys, a feeling of not quite belonging. It’s this emotional precision, rather than narrative or technical virtuosity, that gives Boys Bathing its enduring resonance.

Conclusion: Still Waters Run Deep

Boys Bathing is a painting about presence and distance, community and isolation, youth and its inevitable passing. With minimalist means, Munch offers a richly layered emotional tableau that speaks to the complexities of growing up, watching others, and learning to see oneself.

This isn’t a work that announces itself—it whispers. It invites the viewer to pause, reflect, and remember. Through blurred forms and cool water, Munch evokes the universal experience of being young and uncertain, of standing at the edge and looking inward as much as outward.

In doing so, he creates a work that is not only visually arresting but emotionally unforgettable—a quiet masterpiece that continues to ripple across time.