Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: The Savior as a Source of Comfort

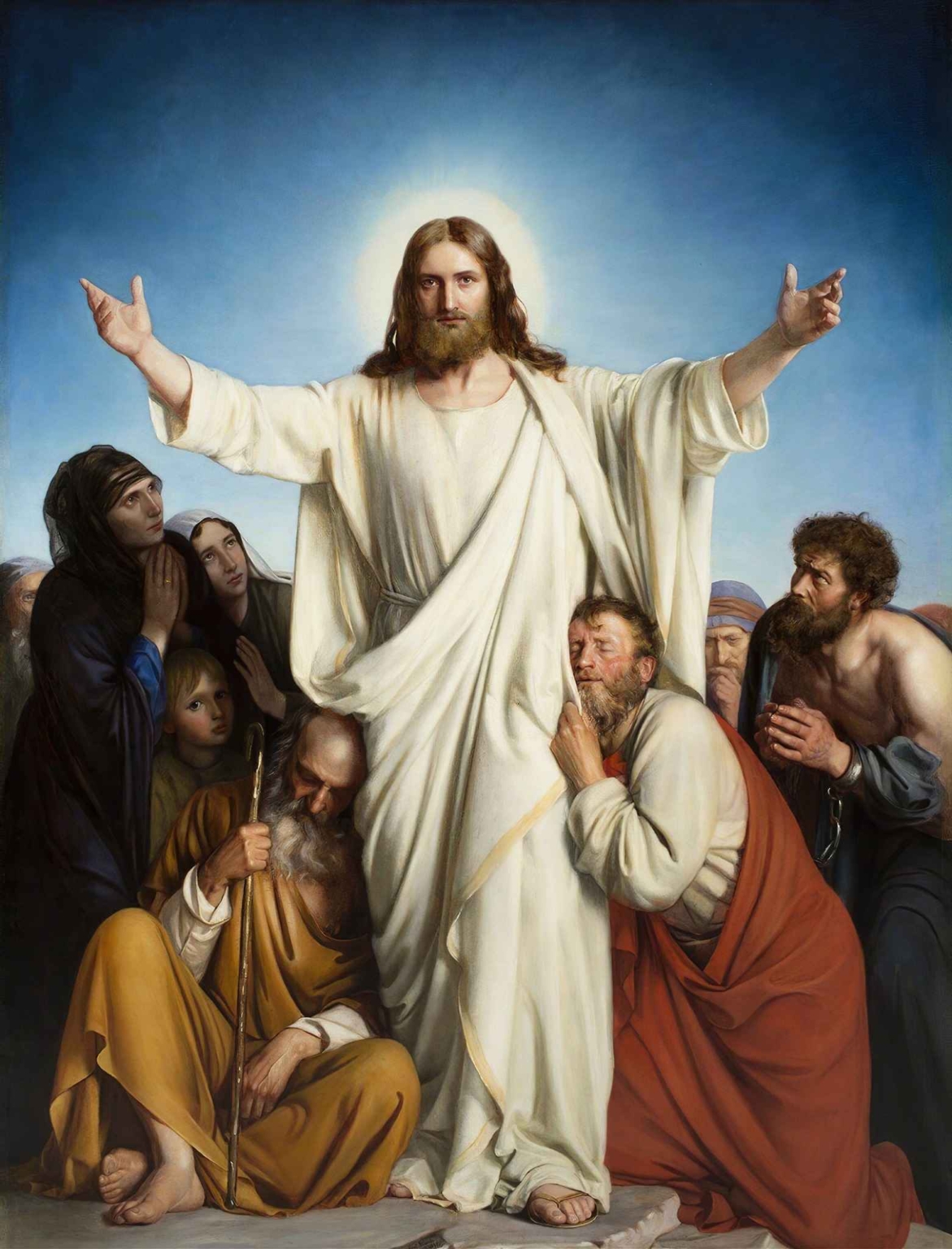

Carl Bloch’s Christus Consolator is one of the most evocative religious paintings of the 19th century, blending theological clarity with masterful composition and deeply felt human emotion. Painted in 1879, this work depicts Christ standing with open arms amid a crowd of weary, broken, and grieving people—each one drawn with intense psychological realism. With its glowing backdrop, serene palette, and dramatic contrasts of suffering and salvation, the painting functions as both sacred icon and narrative drama.

Translated as “Christ the Consoler,” the painting’s title alone captures its essence. Christ is not portrayed in divine judgment or triumphant glory, but as the embodiment of compassion. His open stance, radiant halo, and calm expression offer solace to those burdened by life, sin, or loss. Around him cluster the sick, the weary, the enslaved, and the mourning—a universal congregation of human suffering seeking divine refuge.

This analysis will explore Christus Consolator in terms of its visual structure, symbolic content, historical significance, emotional resonance, and enduring relevance. As a sacred image and artistic achievement, it represents Carl Bloch at his most expressive and spiritually grounded.

Carl Bloch: A Painter of Sacred Humanity

Carl Heinrich Bloch (1834–1890) was a Danish painter whose reputation has endured largely because of his religious works. A student of the Royal Danish Academy of Art and a disciple of the Old Masters, Bloch developed a style that combined academic precision with dramatic realism. He was heavily influenced by Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and the Nazarene movement, all of whom informed his focus on the moral and emotional dimensions of biblical subjects.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who turned toward romantic or allegorical abstraction, Bloch remained committed to narrative painting with a deep moral core. His religious works, particularly those created for the Frederiksborg Castle chapel, became touchstones of Nordic Christian art. Christus Consolator, although not part of that cycle, is often considered one of his greatest standalone achievements—an image that transcends denomination or dogma to speak to the universal longing for divine empathy.

Composition: The Central Figure and Radiant Symmetry

At the heart of Christus Consolator is Christ himself, rendered with a perfect balance of calm authority and gentle openness. He stands centrally with arms outstretched, forming a cruciform silhouette. This compositional strategy not only places him at the literal center of the painting, but also elevates him symbolically as the axis of spiritual consolation. His white robe, glowing with soft light, reinforces purity, peace, and divine presence.

Behind Christ, a deepening blue sky gradates from rich azure near the top to soft illumination around his head, creating a halo effect. This glowing backdrop isolates him from the crowd while also suggesting celestial majesty. Yet there is no throne, no heavenly choir—only light and presence.

The crowd that surrounds him is carefully arranged in an arc, each figure oriented toward Christ, creating a visual rhythm that reinforces the central figure’s magnetic pull. Some figures reach toward him. Others lean against him. One figure clasps the hem of his robe, echoing the biblical story of the woman healed by touching his garment.

In this way, Bloch draws the eye back again and again to Christ—not with theatrical gestures, but with a visual language of intimacy, reliance, and reverence.

Emotional Expression and Human Diversity

What distinguishes Christus Consolator from many religious paintings of its time is the emotional individuality of each supporting figure. Rather than generic representations of sin or sorrow, Bloch gives each person a unique face, posture, and expression. Their differences—of age, gender, ethnicity, social status—reflect the painting’s universal message: Christ consoles all who suffer.

On the lower left, an elderly man with a staff sits with eyes closed, resting his head against the Savior’s side. His expression is one of spiritual release, as if the burdens of life have been momentarily lifted. To his right, a kneeling man—perhaps a penitent or newly forgiven sinner—clutches Christ’s robe and gazes upward with awe and gratitude.

To Christ’s left, women weep, pray, and look upward, their hands clasped or pressed to their hearts. One child peeks out between two women, eyes wide with a mixture of fear and wonder. On the far right, a muscular man with bound hands—clearly a prisoner or enslaved individual—kneels shirtless, his posture both humbled and hopeful.

This range of emotion and representation lends the painting its narrative weight. Each figure becomes a story in miniature, a testament to the many forms of human suffering—and the redemptive promise of divine empathy.

Lighting and Color: Divine Light Amid Earthly Shadow

The lighting in Christus Consolator is a technical triumph that serves symbolic ends. The primary light source emanates from behind Christ, creating a halo-like aura around his head and softly illuminating the surrounding figures. This glow separates him visually and spiritually from the crowd, yet does not isolate him. Instead, the light seems to flow from him into the faces of those closest to him.

The palette is dominated by earth tones—burnt sienna, ochre, navy, gray, and brown—used for the garments of the crowd. These somber colors contrast powerfully with Christ’s luminous white robes and the radiant blue of the sky. The result is a chiaroscuro effect that heightens the emotional and spiritual stakes of the painting.

Bloch’s use of color also deepens the narrative symbolism. The subdued tones of the people’s clothing reflect sorrow, hardship, and humility, while Christ’s pure white suggests transcendence, renewal, and grace. The overall balance of light and dark reinforces the idea of Christ not just as a central figure in space, but as the central figure in the moral and spiritual lives of all around him.

Theology in Paint: Christ as the Source of Consolation

Theologically, Christus Consolator draws on numerous Gospel motifs and passages. The open arms of Jesus recall Matthew 11:28—”Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” The painting visualizes that invitation in literal form: the weary, the burdened, and the broken all come to him seeking solace.

The variety of figures likely alludes to different types of human suffering: physical illness, age and infirmity, captivity, grief, and existential despair. In this way, Bloch builds on the traditions of Catholic and Protestant iconography, merging biblical narrative with a more inclusive spiritual vision.

Unlike triumphalist representations of Christ as Judge or King, this painting foregrounds Christ as Healer and Listener. He does not preach or command—he simply stands, open and ready to receive. It is a deeply incarnational image: Christ among the people, touching them, looking at them, allowing himself to be leaned upon.

Bloch thus visualizes a theology of grace—unconditional, approachable, and eternally present.

Historical Context and Reception

When Carl Bloch painted Christus Consolator, Europe was undergoing significant social, religious, and philosophical transformation. The rise of industrialization, increasing secularism, and widespread political upheaval challenged traditional religious beliefs. In this context, Bloch’s painting offered reassurance. It reaffirmed a compassionate, personal Christianity at a time when many were struggling to reconcile faith with modern life.

In Denmark, Bloch’s religious works gained immediate popularity. His depictions of Christ were widely circulated in prints and reproductions, and Christus Consolator became a beloved devotional image across Protestant and Catholic communities alike. Its clarity, humanity, and theological universality allowed it to transcend doctrinal boundaries.

Over time, the painting has retained its devotional power. It is still used in churches, religious education, and spiritual retreats as a visual focal point for prayer and reflection. In recent decades, art historians have also praised it as a significant example of 19th-century sacred realism, standing alongside the works of Heinrich Hofmann and Léon Bonnat.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

In an age of visual overload and rapid technological change, the quiet stillness of Christus Consolator feels especially resonant. The painting asks nothing of the viewer but presence. It invites a return to the essentials: empathy, light, humility, and hope.

Bloch’s achievement lies not just in his technical skill, but in his ability to communicate timeless spiritual truth through accessible, human imagery. His Christ is neither distant nor abstract. He is profoundly here—radiant and real, luminous yet grounded.

For contemporary viewers—believers and secular admirers alike—the painting offers a space for pause and reflection. It reminds us that consolation is not found in spectacle, but in presence. That divine love does not arrive with thunder, but with open arms.

In this way, Christus Consolator continues to console—not only as a painting, but as a spiritual experience.

Conclusion: A Vision of Healing Through Light

Christus Consolator by Carl Bloch is a masterwork of sacred realism. Through its symmetrical composition, glowing light, and deeply felt emotion, it portrays Christ not as a distant deity but as an ever-present source of healing. Each element—the raised arms, the bowed heads, the quiet shadows—contributes to a scene of profound stillness and gentle power.

At its core, the painting is about nearness: the nearness of sorrow, and the nearness of grace. Bloch’s Christ does not separate himself from the broken. He gathers them, and through his presence, transforms suffering into peace.

Whether viewed as devotional art, academic painting, or visual theology, Christus Consolator continues to speak across time. Its message is clear and comforting: no matter your burden, Christ stands with open arms.