Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: A Revolutionary Self-Assertion Through Art

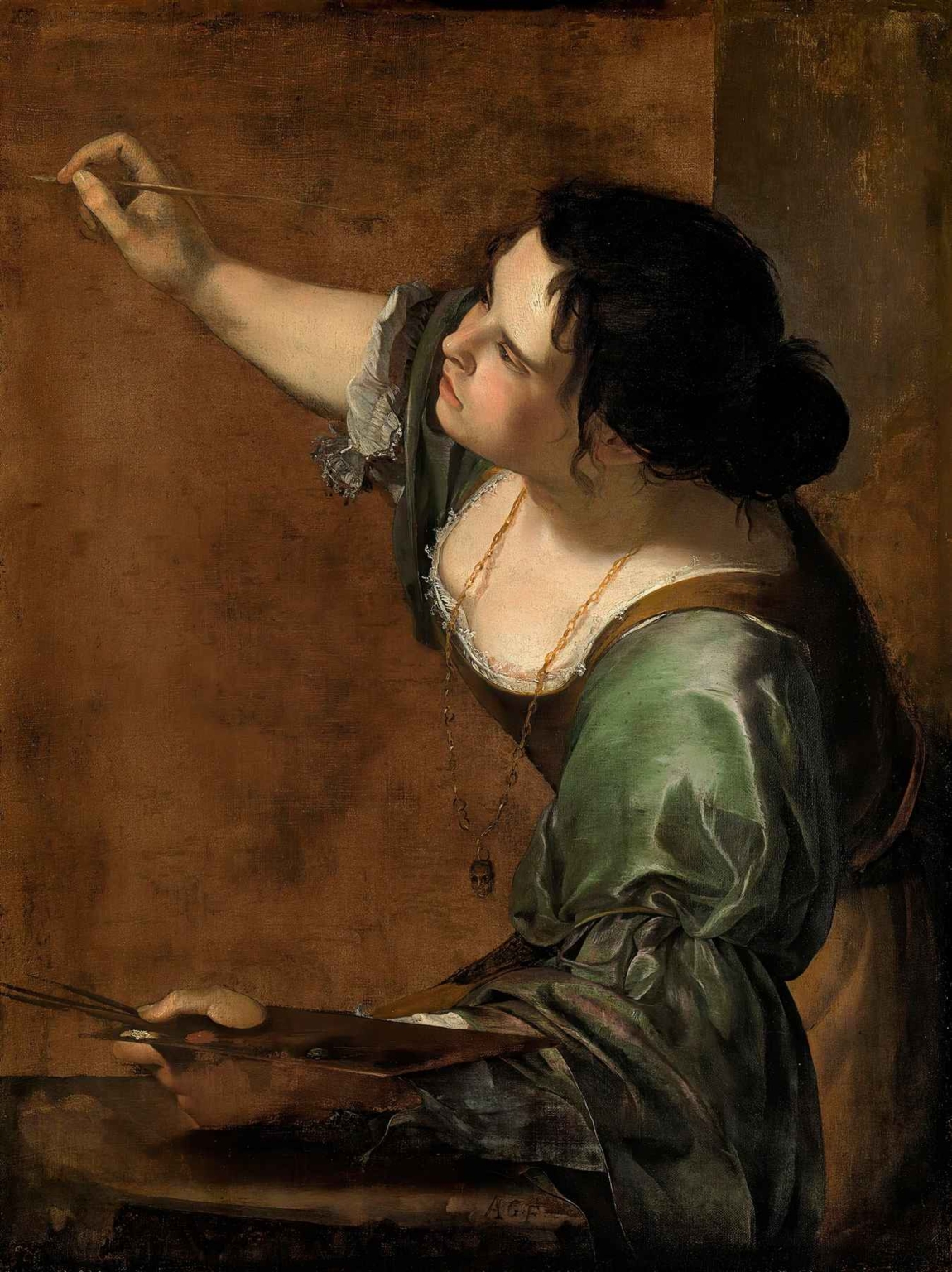

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting is one of the most significant works of Baroque art—not only for its technical brilliance but for its bold conceptual ambition. Painted around 1638–39, this artwork presents Gentileschi not only as an artist but as the living embodiment of painting itself. In a time when women were largely excluded from the professional world of art, Gentileschi’s decision to cast herself in the role of “La Pittura” was both daring and innovative.

This detailed analysis explores the painting’s artistic style, historical background, symbolic layers, and the personal and political stakes behind its creation. As both an image and an idea, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting represents an extraordinary fusion of gender, identity, and intellectual agency—making it one of the most powerful visual statements of the 17th century.

Historical Context: Artemisia Gentileschi in a Male-Dominated Art World

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1656) was born in Rome into a world where artistic training, commissions, and recognition were overwhelmingly reserved for men. The daughter of Orazio Gentileschi, a successful painter and follower of Caravaggio, Artemisia trained in her father’s studio and developed a bold, dramatic style that earned her critical acclaim.

However, her career was marked by gender-based obstacles, including the infamous trial following her rape by the painter Agostino Tassi. Despite this trauma, Gentileschi’s career flourished—first in Rome, then Florence, Venice, Naples, and even London. She secured commissions from aristocrats and royals, eventually becoming one of the first women admitted to the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence.

By painting herself as the allegory of painting—a role traditionally symbolized by a female muse—Gentileschi turned a passive symbol into an active subject. She claimed not only her artistic identity but also redefined what it meant to be a woman in the visual arts.

Composition and Pose: A Dynamic Interruption of the Gaze

In Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, Gentileschi presents herself mid-action: seated, turned three-quarters to the left, and focused intently on her canvas, which is implied but not seen by the viewer. She wears a green satin dress with rolled-up sleeves, revealing the muscular tension in her arms as she holds a brush in one hand and a palette in the other.

Unlike conventional portraits, this is not a static pose. The composition is dynamic—Gentileschi is caught in the act of creation. Her body is slightly contorted, suggesting movement and concentration. Her eyes are directed upward toward her unseen canvas, while her hand stretches out with painterly determination.

This compositional choice departs from traditional allegorical representations of “La Pittura,” which were more idealized and static. Instead, Gentileschi merges allegory with realism, making her self-portrait not only an artistic statement but an assertion of authorship.

Light and Shadow: Tenebrism and Baroque Drama

Gentileschi employs a dramatic chiaroscuro technique—borrowed from Caravaggio—to bathe the subject in a strong, directional light. The dark background enhances the intensity of the figure’s illumination, emphasizing her presence and physicality.

The folds of her dress shimmer with metallic greens and silvery highlights, creating an almost tactile realism. Her skin glows with a natural warmth, while deep shadows define the contours of her face and limbs. This use of tenebrism not only enhances three-dimensionality but also metaphorically reinforces her emergence from obscurity into visibility.

This light does more than reveal; it dramatizes. It declares that the act of painting—and by extension, the identity of the woman painter—is worthy of visual exaltation.

Symbolism: Embodying “La Pittura”

The painting draws from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593), a popular guidebook for allegorical imagery. According to Ripa, the personification of Painting (La Pittura) should be a woman with disheveled black hair, arched eyebrows, a gold chain with a pendant mask (symbolizing imitation), and holding painting implements.

Gentileschi follows this formula closely: her dark hair is loose and untamed, her brows expressive, and a gold chain around her neck features the symbolic mask. Yet by painting herself in this role, Gentileschi transforms the tradition. Rather than merely illustrating an idea, she becomes the idea. She collapses the boundary between allegory and autobiography, between art and artist.

The symbolism extends beyond costume. Her upward gaze and extended arm recall the act of divine inspiration, linking her to classical figures of artistic genius. The green of her dress, often associated with creativity and fertility, reinforces her generative power as a painter.

Gender, Identity, and Agency: A Radical Act of Self-Definition

In 17th-century Europe, women artists were rare, and even more rarely were they given public recognition. Portraits of artists typically showed men in their studios, surrounded by tools and apprentices. Women, when included in art, were usually passive muses, saints, or decorative subjects.

By casting herself as both subject and creator, Gentileschi shatters this norm. Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting asserts not only her technical mastery but her intellectual capacity. She controls the brush, the gaze, and the narrative. She is not being painted—she is painting.

This radical self-representation challenges viewers to reconsider assumptions about gender and genius. It questions the invisibility of women in art history and insists on female agency not just in the studio, but in culture at large.

Technique and Brushwork: Realism with Expressive Depth

Gentileschi’s technical prowess is on full display in this painting. The textures are exquisitely rendered: the sheen of satin, the softness of skin, the glint of jewelry. The play of light across the surface gives the painting a living, breathing quality.

Her brushwork balances precision and fluidity. The rendering of the hand holding the brush is particularly striking—anatomically accurate, yet expressive in its upward stretch. The folds of her dress are painted with sculptural detail, lending volume and weight to the figure.

The background is intentionally plain, likely unfinished, which serves to center all visual attention on the figure and her action. It also invites viewers to imagine the invisible canvas before her—drawing them into the act of creation.

Interpretation and Feminist Readings

Since the late 20th century, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting has become a cornerstone of feminist art history. Scholars have emphasized the painting’s subversion of traditional allegory, its reclaiming of female intellect, and its autobiographical resonance.

This interpretation is supported by Gentileschi’s broader oeuvre, which often centers strong, assertive women from biblical and mythological stories—Judith, Susanna, Lucretia—depicted not as victims, but as agents of justice, resistance, or moral clarity.

In this context, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting reads as a manifesto. It argues for women’s place in the cultural sphere—not as decorative symbols, but as creative minds. It insists on recognition, skill, and authorship. And it does so not through rhetoric, but through brush, pigment, and light.

Comparisons: Gentileschi vs. Her Male Contemporaries

It’s worth comparing this work to other self-portraits by male artists of the period. Rembrandt’s self-portraits often emphasize introspection and psychological depth. Rubens portrayed himself with aristocratic ease. Velázquez inserted himself into royal narratives, such as in Las Meninas, as a quiet but central figure.

Gentileschi, by contrast, places herself at work, in the act of making. There is no vanity, no ornamentation for its own sake. Instead, there is action, purpose, and a focus on the labor of art itself. Her image is not about status but function—redefining what it means to be a painter in a world that often denied women this role.

Reception and Legacy

Though likely painted during her time in England—where she worked briefly at the court of Charles I—Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting remained relatively obscure for centuries. It was rediscovered in the 20th century and is now held by the Royal Collection.

In recent decades, interest in Gentileschi has surged. Exhibitions, academic studies, and popular media have helped reestablish her as one of the most important Baroque artists of her time—not simply as a “woman painter,” but as a painter of universal power.

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting has played a key role in this reevaluation. It has become a symbol of artistic resistance, feminist affirmation, and the ability of visual art to challenge cultural narratives.

Conclusion: A Defining Work of Artistic and Personal Vision

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting is far more than a clever self-insertion into a symbolic tradition. It is a revolutionary act of representation, claiming space in a profession that rarely welcomed women. Through technical mastery, conceptual innovation, and personal courage, Gentileschi painted not just her likeness—but her legacy.

The painting invites viewers to reflect on the power of art to shape identity, disrupt norms, and elevate unseen voices. It challenges the boundaries between symbol and self, between gender and genius. And in doing so, it remains as relevant today as it was radical in its own time.

As both a historical artifact and a modern touchstone, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting continues to inspire artists, scholars, and viewers to reconsider who gets to hold the brush—and what stories that brush can tell.