Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

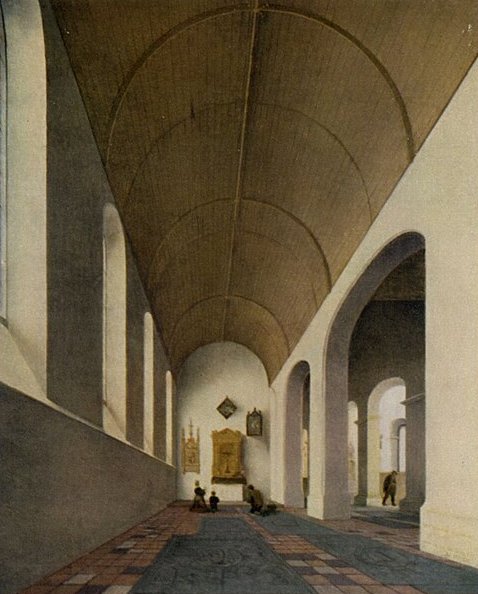

Pieter Jansz. Saenredam’s Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht is one of the most refined and contemplative works of Dutch 17th-century architectural painting. Saenredam, known for his serene and mathematically precise depictions of church interiors, brings an extraordinary sense of stillness and spiritual resonance to this painting. Completed during the height of the Dutch Golden Age, the work reflects not only Saenredam’s technical mastery but also the complex interplay between religion, architecture, and the evolving aesthetics of Protestant Holland.

In this in-depth analysis, we will explore the historical context, composition, use of light, symbolism, emotional resonance, and Saenredam’s enduring legacy.

Historical Context: The Dutch Golden Age and Calvinist Simplicity

The Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht was painted in the mid-17th century, during a period known as the Dutch Golden Age. This was a time of immense wealth, global trade expansion, scientific progress, and unparalleled artistic innovation in the Dutch Republic.

Within the Dutch Republic, religion played a critical role in shaping both society and art. Following the Protestant Reformation, Calvinism became the dominant faith. Calvinist doctrine emphasized simplicity, personal devotion, and a rejection of religious images often associated with Catholic practice. This led to a transformation of church interiors: ornate altarpieces, sculptures, and murals were often removed, leaving behind vast, austere spaces dominated by clean architectural lines, whitewashed walls, and unadorned wooden ceilings.

Rather than depict saints, biblical narratives, or dramatic religious events as many Catholic artists did, Saenredam found his inspiration in the very structure of these emptied sacred spaces. The result was a genre almost unique to the Dutch Republic: architectural interior painting. His work captures not only the physical precision of these churches but also their spiritual quietude.

Pieter Jansz. Saenredam: The Master of Sacred Geometry

Born in 1597 in Assendelft, Pieter Jansz. Saenredam devoted much of his career to painting church interiors, creating an entirely new approach to architectural representation. Unlike earlier artists who treated architecture as backdrop or embellishment, Saenredam made architecture his subject.

What distinguishes Saenredam is his rigorous preparation and almost scientific precision. Before executing his oil paintings, he would make careful on-site measurements, detailed drawings, and perspective studies. Often, years would pass between his initial sketches and the final painting. In the case of Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht, his documentation of the church was meticulously executed, resulting in an image that balances realism with a transcendent sense of order.

Yet, Saenredam was not merely copying what he saw. His paintings are not strict reproductions but carefully composed meditations on space, light, and structure. In this way, he elevates architecture into a spiritual experience, much like Vermeer elevated simple domestic scenes into meditative masterpieces.

Composition and Spatial Harmony

The composition of Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht is built upon masterful control of perspective. The viewer’s eye is drawn down the length of the Antonius Chapel, toward the distant altar, which stands as a quiet focal point. The receding vaults of the high wooden ceiling and the orderly rhythm of the arched windows along the left wall create a perfect linear recession that enhances the sense of depth.

The floor tiles, with their contrasting diagonals, further emphasize the precision of the spatial geometry. This compositional harmony produces an almost hypnotic rhythm as the viewer’s eye glides naturally through the space.

On the right, a large archway opens into a secondary chamber, giving the viewer a glimpse of the nave and expanding the sense of three-dimensionality. This use of multiple perspectives within a single frame is a subtle but sophisticated device that Saenredam employed to create both visual complexity and balance.

Saenredam’s careful control over architectural lines and geometry contributes to the painting’s serenity. Every curve, shadow, and structural element contributes to an atmosphere of calm contemplation.

The Use of Light: An Atmosphere of Quiet Divinity

Light plays a central role in Saenredam’s work. In Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht, natural light filters gently through the tall arched windows on the left, casting soft, diffuse illumination across the whitewashed walls and floor.

The light does not fall dramatically, as in many Baroque paintings, but rather infuses the entire space with even clarity. This soft light reflects the Dutch atmospheric conditions—often overcast and diffused—and enhances the feeling of peaceful stillness.

The interplay between light and shadow subtly articulates the architectural forms. The ceilings are delicately shaded to suggest the curve of the vaults, while the columns and floor receive more direct light, guiding the viewer’s eye along the church’s interior. This controlled lighting creates an almost sacred luminosity without the need for overt religious imagery.

In many ways, Saenredam’s treatment of light mirrors the Calvinist emphasis on the inward, personal experience of the divine. The church becomes not a place of spectacle but one of silent reflection, where architecture itself serves as a vessel for spiritual meditation.

The Human Presence: Small Figures, Grand Space

Though architecture is the primary subject, Saenredam includes several small human figures scattered throughout the scene. Some appear to be engaged in quiet conversation, while others sit or kneel, perhaps in prayer or contemplation.

These diminutive figures serve several purposes:

Scale and proportion: Their small size reinforces the grandeur and vastness of the church interior.

Narrative suggestion: The figures imply daily life continuing within the sacred space, hinting at the church’s role as both a place of worship and community gathering.

Emotional connection: Their presence softens the austerity of the composition, inviting viewers to imagine themselves inhabiting the space.

Importantly, the figures do not distract from the architecture but rather complement it, humanizing the immense space without breaking its meditative stillness.

Symbolism: Architecture as Theological Statement

While Saenredam’s paintings may seem purely observational at first glance, they contain layers of symbolic meaning closely tied to the religious and cultural climate of 17th-century Holland.

Purity and Simplicity: The unadorned white walls reflect Calvinist values, emphasizing the removal of religious images that were considered idolatrous distractions from God’s word.

Order and Geometry: The perfect alignment of arches, windows, and vaults symbolizes divine order and the rational structure of creation.

Light as Divine Presence: The gentle, pervasive light suggests God’s omnipresence—not as a blinding force, but as a quiet, sustaining illumination.

Through these choices, Saenredam transforms mere architectural depiction into spiritual meditation, allowing the viewer to experience the sacred in the silence of proportion and light.

The Janskerk: A Real and Transformed Space

The Janskerk (St. John’s Church) in Utrecht was originally built in the 11th century as part of a Benedictine monastery. After the Reformation, the church was converted for Protestant use, and much of its original decoration was removed.

Saenredam’s portrayal reflects the church’s post-Reformation state. The sparse ornamentation, clean walls, and absence of Catholic iconography are accurate to its 17th-century appearance.

However, art historians suggest that Saenredam may have subtly idealized or altered certain architectural elements to enhance the composition’s visual harmony. This blend of observation and artistic refinement was characteristic of his working method, resulting in paintings that feel simultaneously real and transcendent.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

The emotional effect of Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht is not one of overt drama or narrative tension but of profound serenity. The vast, quiet space seems to breathe, inviting contemplation and inward reflection.

For 17th-century viewers, this image would resonate with the Calvinist emphasis on private devotion and silent prayer. For modern viewers, the painting’s stillness may evoke a similar sense of meditative calm, making it timeless in its appeal.

Unlike many religious paintings that aim to overwhelm the senses, Saenredam’s interiors offer an almost minimalist spirituality—one rooted in space, proportion, and the quiet dignity of sacred architecture.

Saenredam’s Legacy: A Unique Voice in Dutch Art

In the context of Dutch Golden Age painting, Saenredam’s work stands apart. While many of his contemporaries like Rembrandt, Frans Hals, or Vermeer focused on portraits, genre scenes, or biblical narratives, Saenredam cultivated a highly specialized niche: architectural interiors as subjects worthy of artistic reverence.

Architectural Accuracy: His methodical approach to perspective and measurement influenced later architectural rendering, blending art with early scientific observation.

Spiritual Abstraction: In many ways, Saenredam anticipated aspects of modern abstraction, finding beauty in pure form, line, and light.

Cultural Record: His paintings preserve visual records of churches as they appeared shortly after the Reformation, providing invaluable historical documentation.

Today, Saenredam is celebrated for his ability to translate physical space into visual poetry, elevating architecture into a spiritual experience that continues to inspire viewers centuries later.

Conclusion: Sacred Silence Captured in Paint

Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht exemplifies Pieter Jansz. Saenredam’s singular ability to transform simple church interiors into profound visual meditations. With its masterful control of perspective, gentle illumination, and quiet dignity, the painting transcends mere documentation to offer an experience of spiritual stillness.

In an age of religious turmoil and political change, Saenredam’s paintings provided a different kind of religious art—one that embodied the quiet, inward spirituality of the Dutch Reformed tradition. His work invites viewers not to witness grand biblical dramas, but to step into the empty space and find their own moment of reflection beneath the soaring vaults and whispering light.

In this way, Interior of the Janskerk in Utrecht remains one of the most compelling examples of how architecture, faith, and artistic discipline can merge into something far greater than the sum of its parts—a silent sermon in paint, offered to the eyes and the soul alike.